The former Little Stevie Wonder had long since dropped that child star-era prefix from his name. Still, Innervisions, with its very adult themes, was where he became a man in full.

The album arrived amid an almost-unfathomable run of important recordings. Yet it emerged as one of his very best — mainly because Wonder delved so deeply into the failure of the ’60s and then constructed a path out of that crushing disappointment.

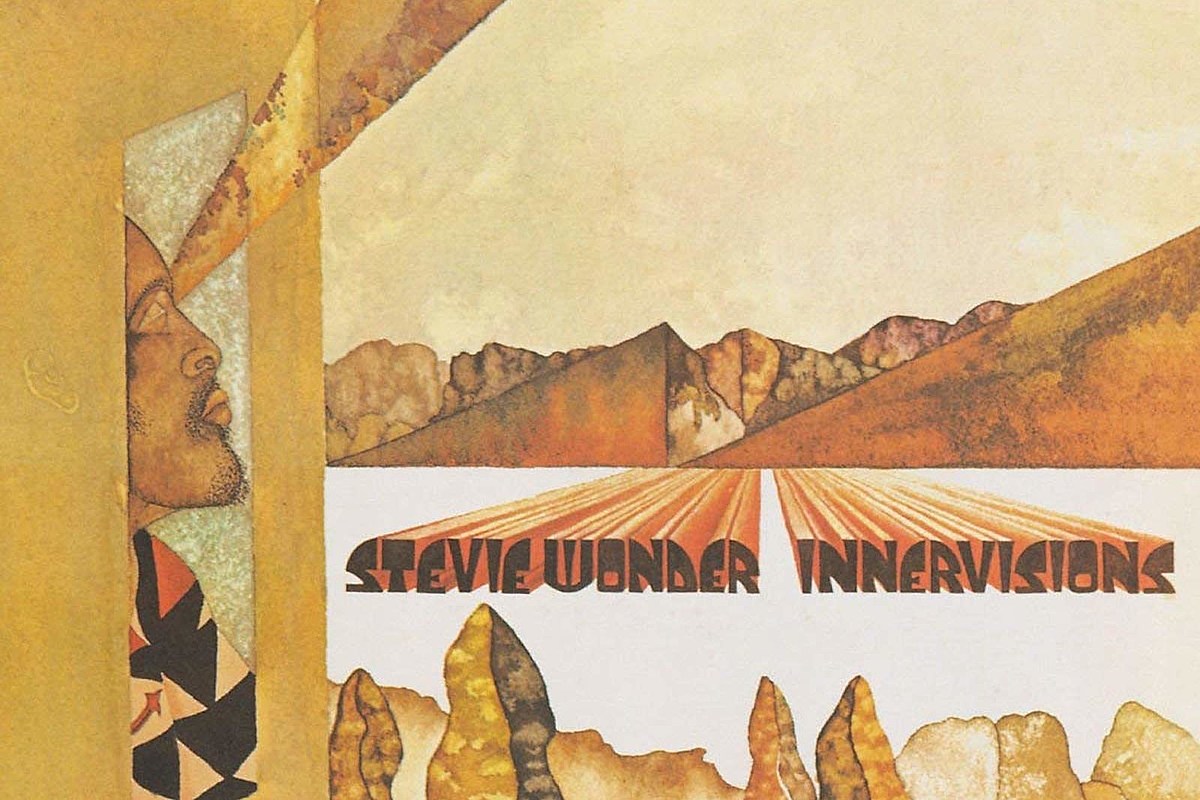

The decade’s promise of peace, of prosperity and of racial justice must have already seemed very far away as Innervisions was released on Aug. 3, 1973, yet Wonder was steadfast in his convictions, unwavering in his thrilling creative experimentation, and unflinching in his willingness to lay bare the challenges and remaining opportunities. Innervisions – somehow his 16th album, though he was only 23 – didn’t just portray Stevie Wonder as visionary via its striking cover image by Efram Wolff. It proved that he, in fact, was.

Wonder had risen to fast fame as a Motown prodigy, boasting a sun-surface smile with an embryonic stage presence that shone even brighter. Innervisions looked past all of that, toward the most serious, most complex topics Wonder had ever tackled. “We as a people are not interested in ‘baby, baby’ songs anymore,” he said back then. “There’s more to life than that.”

The result was a remarkably tough-minded examination of life’s seemingly intractable problems: From the scarring impact of drugs (the album-opening “Too High”) to this world’s soul-deadening hypocrisy (“Jesus Children of America,” “He’s Misstra Know-It-All,” which was aimed at the Watergate-era White House) to the stark choices left for those trying to traverse a tough urban landscape (“Living for the City”), the trenchant Innervisions pulled no punches. Stevie Wonder crafted every word himself, and in so doing spoke more clearly than ever.

Then he went further. Wonder’s continuing solo experiments with the TONTO synthesizer, an instrument only just then gaining interest in the black community, represented an exciting new sound for R&B — and they were very much solo experiments. Seven of the nine songs here were played in their entirety by Stevie Wonder. Absent other collaborators, his clever blending of rock, soul, Latin, R&B, reggae and gospel styles was all the more impressive.

Listen to Stevie Wonder’s ‘Living for the City’

That last genre was of particular note, as Wonder finally allowed his faith to move to the fore. “It was all about belief; it was all about spirituality,” Malcolm Cecil, associate producer and co-creator of the TONTO synth, told Wax Poetics in 2013.

“We all had that spiritual thing in common,” Cecil added. “In addition to the social consciousness, you bring spirituality into it, you bring the love into it, then you bring the musicality into it then the art into it, then the engineering perfection then the constant attention to detail – and that’s when you get an album like Innervisions.”

Darkness does not prevail, and that remains one of the more intriguing elements of this often brutally frank project. Along the way, Wonder’s “Visions” reminds those who feel overburdened that “today’s not yesterday, and all things have an ending.” With a lyrical sweep that framed frank social realism with a fierce struggle against the dying of the light, Wonder’s narrative approach mirrored the complexity of living in the United States — both then and now.

“Innervisions gives my own perspective on what’s happening in my world, to my people, to all people,” Wonder told The New York Times back then. “That’s why it took me seven months to get together. I did all the lyrics, and that’s why I think it is my most personal album. I don’t care if it sells only five copies: This is the way I feel.” It did far better than that, of course.

A No. 4 hit in the U.S., Innervisions would build upon the commercial successes of Talking Book, becoming Wonder’s second-consecutive No. 1 album on the R&B charts — and his first-ever Top 10 U.K. album. Three singles were Billboard Top 20 pop hits: “Higher Ground” (No. 4), “Living for the City” (No. 8) and “Don’t You Worry ‘Bout a Thing” (No. 16), with the first two topping the R&B chart as well. Wonder also had a Top 10 hit in Britain with “He’s a Misstra Know-It All.” Innervisions then helped Wonder to a trio of Grammys, for best R&B song (“Living for the City”), best engineered non-classic recording and for album of the year.

Those accolades feel just as well-earned today. Innervisions remains perhaps Wonder’s most cohesive album. The music still sounds street-level relevant – and the messages do too. Unfortunately, some of that can be attributed to the snail’s pace of progress. At the same time, however, the timeless nature of Wonder’s insights simply can’t be denied. This is more than a coming-of-age album; Innervisions is, quite simply, an album for the ages.

Top 25 Soul Albums of the ’70s

There’s more to the decade than Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder, but those legends are well represented.