Jorge Ben never quite fit any of the Brazilian music trends of the 1960s and 1970s. He was friends with seemingly everyone, though: Ben was a celebrated guest on Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil’s avant-garde TV show Divino Maravilhoso. Around the same time, he also appeared on O Fino da Bossa, presented by Elis Regina and Jair Rodrigues, which catered to a more MPB-oriented audience.

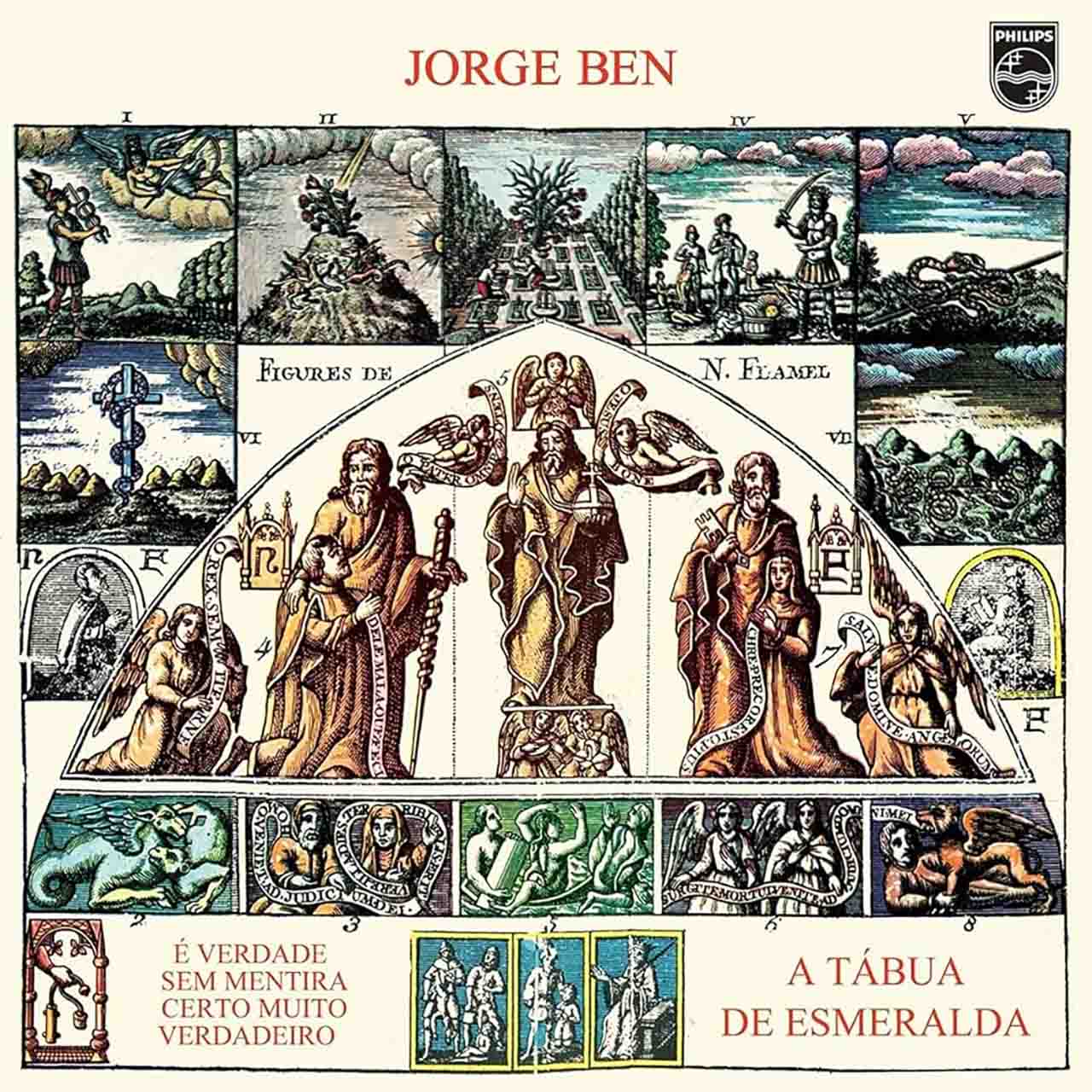

With 1974’s A Tábua de Esmeralda, Ben literally and figuratively combined all of his interests into one of Brazilian music’s most beloved albums. Heavily influenced by the new wave of mysticism that was taking Brazilian music by storm (Raul Seixas’ Krig-Ha, Bandolo! and Tim Maia’s Racional Vols. 1 & 2 are other great examples), A Tábua de Esmeralda drew inspiration from the world of hermeticism and alchemy, specifically the work of Nicolas Flamel: “I have much respect for the work of an alchemist,” Ben declared at the time of the album’s release, “because he dedicates his life to studying and researching with unparalleled faith and perseverance.” Though Ben would later confess that his attempts at deciphering ancient texts might have resulted in less than accurate interpretations, his fascination with this universe can be observed not only in the album’s lyrics but also in its cover, which was assembled from images found in a book by Flamel.

Listen to Jorge Ben’s A Tábua de Esmeralda now.

Jorge Ben’s flirting with the esoteric isn’t the album’s sole theme. His Afro-Brazilian identity, which had already taken center-stage in many of his previous compositions (“Negro É Lindo,” “Cassius Marcello Clay,” “Crioula”), is also represented in A Tábua de Esmeralda, notably through the song “Zumbi.” A direct reference to settlement leader Zumbi dos Palmares, the song features numerous allusions to colonialism and slavery, employing strong visual motifs (“white cotton” picked by “black hands”) and geographical name-dropping (“Angola, Congo, Benguela”) to construct a vivid picture.

A Tábua de Esmeralda’s lyrical experimentation, allegorical references, and innovative approach to samba-rock are all reasons that the album remains one of Ben’s best. The record also showcases a unique sensibility in terms of identity performance, prompting journalist Tiago Ferreira to name Jorge Ben “the most Brazilian of all musicians” while describing the album as “alchemist-samba.” Indeed, A Tábua de Esmeralda played an important ideological role in Black Rio, a movement often regarded as the Brazilian response to Black Power.

Ranking sixth on Rolling Stone Brazil‘s list of the Best Brazilian Albums of All Time, A Tábua de Esmeralda‘s enduring legacy and pioneering contribution to Brazilian music are perhaps best summarized by Aramis Millarch’s 1974 review of the album: “Very few artists managed not to follow any pop music trend, letting music trends follow them instead. [This record] demonstrates the extent and the integrity that Jorge Ben has managed to achieve with his work.” Or, as journalist Maris Clara Silva once put it, this album is forty minutes of “peace, joy, and brotherhood.”

Listen to Jorge Ben’s A Tábua de Esmeralda now.