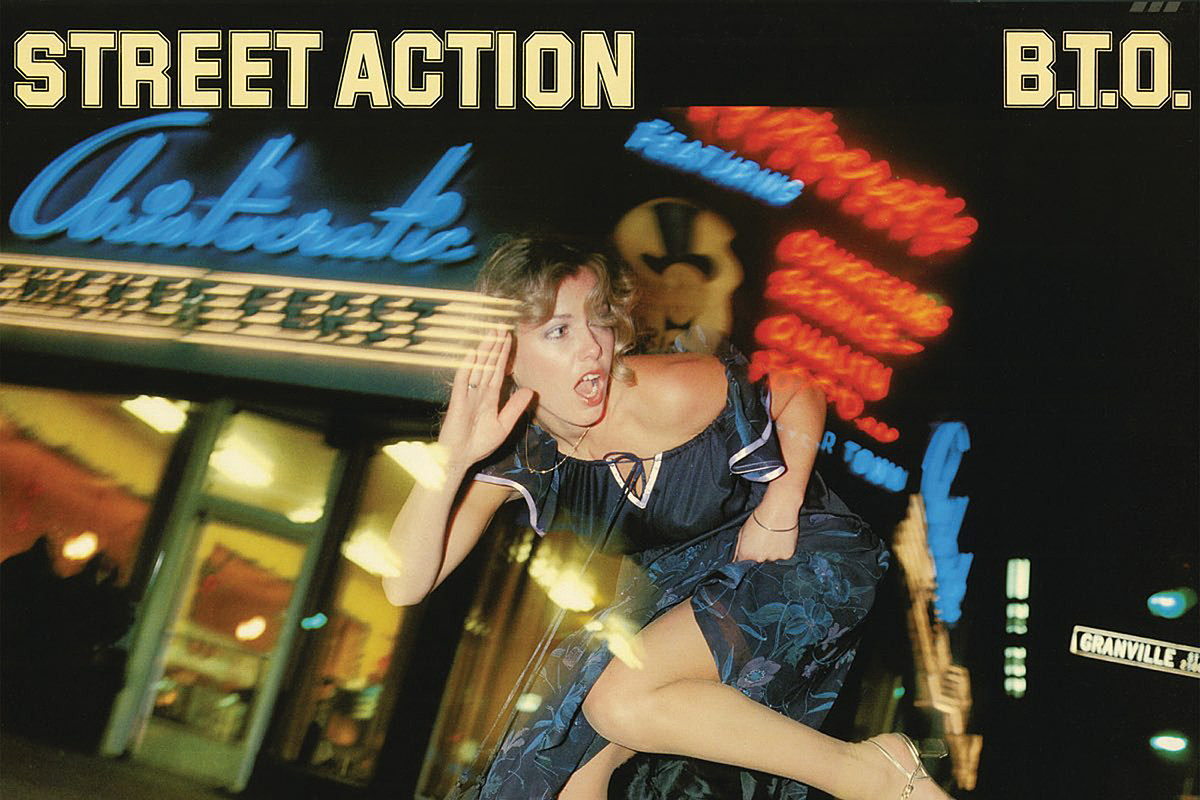

The arrival of Street Action in February 1978 officially ended Bachman-Turner Overdrive’s reign of success. This was also the Canadian group’s first album without co-founder Randy Bachman and the beginning of the end for the band.

Bachman had broken away from the pack before, having departed from the Guess Who at the height of their popularity. At that time, he’d seen a troubling and damaging cycle of drug abuse that was destroying many of his peers in the industry.

So Bachman laid down conditions as he formed the band that would eventually morph into Bachman-Turner Overdrive, after an initial stint playing folk music as Brave Belt: There would be no overindulgence in partying. Everyone had to be similarly 100% committed to the cause. Bachman was self-financing the new project, after all.

“Nobody will work with me; I’ve left the No. 1 band in the world,” he told UCR. “American Woman” was the No. 1 album and single, and I left. I’ve got to do this on my own. There’s nobody helping me. If you can’t keep my rules, do not be a hindrance to me. I’ll get somebody else.”

He had a winning formula. Starting in 1973, Bachman, brothers Tim and Robbie, and Fred “C.F.” Turner placed three albums in the Canadian Top 10 over their first 18 months. Bachman-Turner Overdrive’s second and third albums matched that success in the United States. By 1974, they had amassed three major hit singles, “Let It Ride,” “Takin’ Care of Business” and the mock-stuttering “You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet,” which gave the group their first chart-topper.

Bachman-Turner Overdrive’s third album, Not Fragile, also landed at the top that same year. Cracks began to develop in the foundation once they began working on the follow-up, 1975’s Four Wheel Drive. Interpersonal issues and an excessive amount of time touring finally led him to depart following 1977’s Freeways. “We were all tired and we had all been on the road since 1972 literally doing 300 dates a year,” he explained to UCR. “Not knowing our wives and kids, not knowing each other, getting sick of each other, being stuck in a car and a van all of the time.”

They had quarreled over the direction of Freeways, which found Bachman-Turner Overdrive going in a much more experimental direction, moving away from their usual guitar-driven approach. Bachman pressured the rest of the members to follow a path they were not happy about. “It was mutiny. I was captain of the ship,” he told the Edmonton Journal, “and the crew just said: ‘We don’t want to go to South America. We want to go to Coney Island.’”

Disco was also creeping in and the same excesses he had decreed would not be a part of the band’s inner workings eventually come into the mix. “The minute everybody was a millionaire and a superstar, they all started doing that stuff,” Bachman told UCR. “It was time to leave.”

Listen to B.T.O.’s ‘Down the Road’

According to Turner, he was against the idea of continuing Bachman-Turner Overdrive in Randy’s absence. Robbie Bachman and guitarist Blair Thornton – who replaced Tim in 1974 while the band was touring their second album – were pushing to keep the group active.

Turner split the lead vocals with Randy and he was well aware that having him out of the mix was going to change things significantly. “I knew the band was not the same as what people had come to expect,” he said in Bachman’s memoir, Takin’ Care of Business. “I was carrying the whole thing.”

Worse, he had seen the movie before, watching what happened after Bachman left the Guess Who. “It wasn’t that the Guess Who wasn’t any good after that, but in the public’s eye and especially in the critic’s eye, it was like someone had yanked an arm off and it would never be the same again,” Turner said. “I thought the same about B.T.O. I felt I owed it to Robbie and Blair to give it a shot, but I really lost interest in that period.”

There were additional complications when they learned Bachman owned the band name. They negotiated for more than a year with their former bandmate, finally purchasing the rights to use the name “B.T.O.” for $18,000. Additionally, it was agreed that they would not use “Bachman” in the marketing and advertising of the new group – only “B.T.O.” to avoid confusion in the marketplace.

As work commenced on Street Action, they brought in former April Wine bassist Jim Clench so Turner could shift to being more of a proper frontman – and also play guitar. “Fred tried to play guitar and Fred didn’t look like he should play guitar,” band manager Bruce Allen said in Takin’ Care of Business. “He was this lumberjack bass player stomping about the stage. He should have been playing bass.”

Clench proved to be a major asset on Street Action, taking lead vocals on three of the album’s tracks, with “Down the Road” and “A Long Time for a Little While” being particularly noteworthy. “Madison Avenue” sticks out as a bit of an outlier, mixing a calypso feel with a jazzy saxophone solo, but overall the group returned to a heavier and more familiar rock sound with Street Action.

It wouldn’t be enough. Months after the album was released, Turner was seeing the writing on the wall. “I think this band can do it,” he told the North Bay Nugget that June. “If not, we don’t need to keep banging our heads on the wall. I love country music. I have a wife and three kids. There are other ways I can continue.”

The reconstituted B.T.O. followed Street Action with 1979’s Rock n’ Roll Nights, which found them relying more heavily on outside songwriters. They disbanded in 1980 after touring wrapped for the record and would reunite periodically, starting in 1983 when Bachman returned to the fold. The band recorded only one more studio album, 1984’s Bachman-Turner Overdrive.

Top 100 ’70s Rock Albums

From AC/DC to ZZ Top, from ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ to ‘London Calling,’ they’re all here.