Blue was more than a career-making album for Joni Mitchell. Every wall had come down, resulting in a crushingly vulnerability that created a blueprint for the modern confessional album.

The triumph was that this 1971 LP did what many singer-songwriters aspire to do: Blue took the specific and made it universal. Mitchell resonated deeply with listeners, even if they didn’t know the first thing about her personal life. Of course, that kind of vulnerability came with a price. Mitchell’s fame skyrocketed after the release of Blue and it left her inevitably wondering: After you bare your soul, what do you do?

For Mitchell, the answer was getting back to the garden. She sold her Laurel Canyon home and fled California in favor of her home country of Canada, taking up residence in a small stone house located on British Columbia’s Sunshine Coast. Celebrity had hit Mitchell hard and physical isolation appeared the only refuge.

“The idea of people at my knees was just horrifying to me,” she explained in the 2003 documentary A Woman of Heart and Mind. “I lived with kerosene, stayed without electricity for about a year. I was going down and with that came a tremendous sense of knowing nothing.”

Not only was fame itself taking a toll, but Mitchell also struggled with the way Blue was being perceived by fans and critics: “I was being told that people were horrified by the intimacy of it,” she told the Toronto Star in 2013. “People said it was shocking. It wasn’t. It was about human nature. It’s all I had to work with. It’s a soul trying to find itself and seeing its failings and having regrets. What’s so horrible about that?”

Fleeing to Canada was one way to wrestle with the fact that Mitchell didn’t know where her career was headed. “Some people would call it a nervous breakdown,” she added, “but I just hit that pocket that everyone does on some point in their journey through their lives – that identity crisis, that ‘Who am I, really?’ You’re lucky if it hits you early like it did with me.”

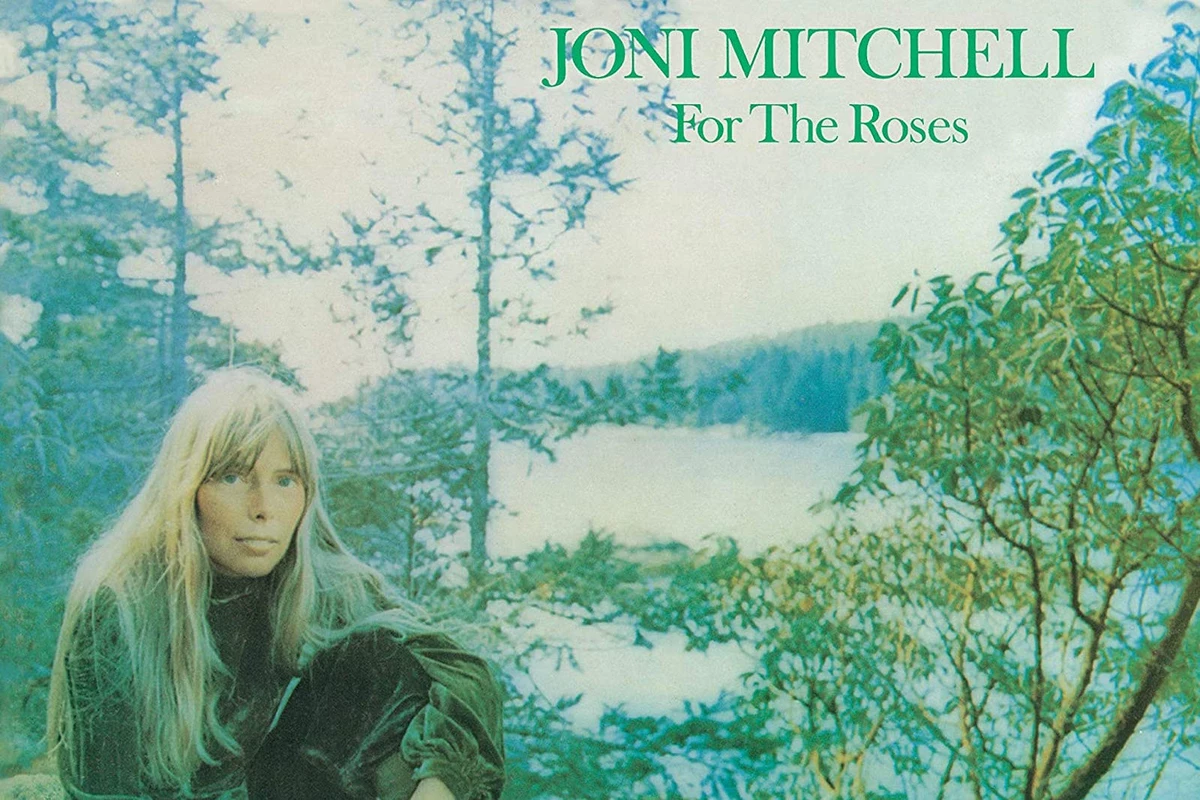

Listen to Joni Mitchell’s ‘For the Roses’

In an effort to better understand herself, Mitchell bought and read “every psychology book I could lay my hands on,” from Jung to Freud. One publication stood out in particular, Beethoven: His Spiritual Development by J.W.N. Sullivan. Mitchell wasn’t eager to compare herself to one of the world’s most famous composers; instead, she was coming to terms with how fame could change an artist’s perspective.

“It was all about his struggles, and self-doubts and his worries about how his work was being received and what it all meant on a deeper level and, of course, about his going deaf,” she told the Star. “At the time, that’s just what I was thinking about too. How am I going to get back in the saddle? And what about the audience? Would you still love me if you knew what I was really like?”

Mitchell’s self-imposed exile ultimately brought clarity – and new songs, too. “Depression,” she admitted, “can be the sand that makes the pearl.” The results, found on Mitchell’s fifth album For the Roses, were at once a continuation of her vulnerability and a modest step toward something more experimental. Mitchell still wrote and sang about people and places she knew, but she had undeniably changed since leaving California, both emotionally and creatively.

She utilized the lower register of her voice more, and allowed the instrumentation (French horns, other woodwinds) and arrangement of several tracks to flow more loosely. Both hinted at her eventual drift toward jazz in the coming years, as For the Roses provided a sort of sweet spot between the poignancy of Blue and the avant garde attitude of 1974’s Court and Spark.

Of course, Mitchell wasn’t thinking about the music in those terms. For the Roses was, in several respects, Mitchell’s response to things that had transpired over the last few years.

Perhaps the most tender of these was her relationship with James Taylor, whom Mitchell began dating in 1970. By November 1972, Taylor had called things off, earned an enormous level of fame with his own music, slipped into serious substance abuse and married another woman – Carly Simon, no less. “Some turn to Jesus and some turn to heroin,” Mitchell sang on album-opening track “Banquet,” “waiting for that big deal American Dream.”

Mitchell further addressed the matter on the album’s next track, “Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire,” whose title itself painted an image of addiction. Mitchell described it to Sounds Magazine in 1972 as “a real paranoid city song — stalking the streets looking for a dealer.” James Burton played a subtle electric guitar, while Tom Scott offered a jazzy, soprano saxophone part. “Bashing in veins for peace,” she sang.

Listen to Joni Mitchell’s ‘Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire’

Even if Taylor had never touched a needle or anything else, Mitchell still recognized the struggle his thrust into the spotlight had created. Taylor had only enjoyed moderate success until the release of his second album, 1970’s Sweet Baby James, which propelled him to the top of the charts. Mitchell saw it all unfold in real time and recognized parts of herself in Taylor.

“I was watching his career and I was thinking that as his woman at that time I should be able to support him,” she told Sounds. “And yet it seemed to me that I could see the change in his future would remove things from his life. I felt like having come through, having had a small taste of success, and having seen the consequences of what it gives you and what it takes away in terms of what you think it’s going to give you. Well, I just felt I was in no position to help. I knew what he needed was someone to support him and say it was all wonderful, but everything I saw him going through I thought was ludicrous – because I’d thought it was ludicrous when I’d done it.”

Much of this sentiment came through on the title track from For the Roses, which Mitchell would later describe as her “first farewell to show business.” Having physically and emotionally distanced herself from the industry, Mitchell had more time to consider what it had done to her. “To me, this was an unfair, crooked business and it has nothing to do with real talent,” she told Los Angeles Times in 1996. The song’s lyrics reflected this disenchantment: “In some office sits a poet and he trembles as he sings / And he asks some guy to circulate his soul around.”

The title came from the nickname of the Kentucky Derby, which is called “The Run for the Roses.” “You know what that’s all about,” Mitchell once said when introducing the song, “you take this horse and he comes charging into the finish line and they throw a wreath of flowers around his neck – and then one day they take him out and shoot him.”

For the Roses was Mitchell’s first album for Asylum records, which had been founded in 1971 by David Geffen along with Mitchell’s manager at the time, Elliot Roberts. “I was their first racehorse, so to speak,” she said in 2017’s Reckless Daughter: A Portrait of Joni Mitchell.

Geffen was also the man responsible for the album’s tongue-in-cheek single, “You Turn Me On, I’m a Radio.” Mitchell wrote it after he asked her to include a radio-friendly song. “I wanted her to sell a lot of records,” Geffen explained plainly in Reckless Daughter.

Listen to Joni Mitchell’s ‘You Turn Me On, I’m a Radio’

The outside prodding worked — “You Turn Me On, I’m a Radio” became Mitchell’s first Top 10 hit in Canada and her first Top 40 hit in the U.S. – even if it was a silly idea: “To write a hit song because David Geffen wants you to have a hit,” as Mitchell’s drummer Russ Kunkel pointed out in Reckless Daughter, “is like saying ‘Go take a paper route so that you can do public service,’ when she had already worked as a candy striper.” It also turned out to be a splendid opportunity for Mitchell to reconvene with old friends.

“You Turn Me On, I’m a Radio” was originally cut with David Crosby, Graham Nash and Neil Young – though, in the end, only Nash’s harmonica part was kept. (“There were too many chefs, you know,” Mitchell told Sounds. “We had a terrific evening, a lot of fun, and the track is nice, but it’s like when you do a movie with a cast of thousands. Somehow I prefer movies with unknowns.”) Stephen Stills, the final member of CSNY, added guitar to “Blonde in the Bleachers.”

There was a touch of retaliation on For the Roses, too. Songs like “Woman of Heart and Mind” – where she sings “drive your bargains, push your papers / win your medals, fuck your strangers” — indicated that Mitchell didn’t intend to be dismissed, no matter how fractured or exposed she may have sounded on Blue. “All people seemed interested in was the music and the gossip. I felt then that the music spoke for itself and the gossip was unimportant,” she told Circus in 1973. “I have, in my time, been very misunderstood.”

Then there the cover art. Mitchell chose a nude image taken by Joel Bernstein from afar, where she’s standing on a rock facing away from the camera and toward the ocean. “It was going to be like [Belgian artist Rene] Magritte or ‘Starry Night,'” she said in Reckless Daughter, “and it’s a very innocent nude. It’s like Botticelli’s Aphrodite. I’ve had a few bum comments. It’s a nice bum; it’s no big deal. The cock of the leg is Aphrodite rising from the clamshell. It’s an art posture borrowed from paintings.”

Elliott Roberts stepped in at the last moment with a pertinent question: “Joan, how would you like to see $5.98 plastered across your ass?” Mitchell decided to move the photo to the album’s inner gatefold.

Listen to Joni Mitchell’s ‘Judgement of the Moon and Stars (Ludwig’s Tune)’

In the end, For the Roses got even closer to the bone than Blue had. A line from “Judgement of the Moon and Stars (Ludwig’s Tune)” seemed to make reference to Taylor, whose first album was released on the the Beatles’ boutique label: “In the court, they carve your legend with an apple in its jaw.” Elsewhere, “See You Sometime” found Mitchell urging the song’s subject to “pack your suspenders” – after Taylor memorably wore them on the cover of 1971’s Mud Slide Slim and the Blue Horizon.

“Everyone who writes songs writes autobiographical songs, and hers are sometimes really disarmingly specific,” Taylor told Rolling Stone in 1973, when asked for his thoughts on For the Roses. “This is her most disarmingly specific album.”

Mitchell admitted that some of the songs were “directly personal,” but that “others may seem to be because they’re conglomerate feelings.” Interestingly, however, Mitchell felt she’d finally freed herself from the constraints of deeply confessional songwriting. “I was too close to my own work,” she told Sounds. “Now I’ve gained a perspective, a distance on most of my songs. So that now I can feel them when I perform them, but I do have a certain detachment from the reality of the story.”

Released in November 1972, the LP was met with critical acclaim and reached No. 11 in the U.S. and No. 5 in Canada. For the Roses was added to the National Recording Registry in 2007 by the Library of Congress, who described it as a moment “in which all the elements of her creative palette are in perfect balance.”

Apart from the accolades, the album allowed Mitchell to revive herself. Writing these songs, she said, felt like a “release valve.” They also served as a springboard: “I feel I want to go in all directions right now, like a mad thing right!” she told Sounds. “No, I don’t feel trapped in this held-back careful image. … But rushing ahead of ideas is bad. An idea must grow at its own pace. If you push it and it’s not ready, it’ll just fall apart.”

Rock’s 100 Most Underrated Albums

You know that LP that it seems like only you love? Let’s talk about those.