The song was ready. Everything was there: Bass, drums, extra percussion and a smattering of guitars. The country-rock track, recorded over numerous sessions, was ready to appear on R.E.M.’s new album. There was only one slight problem. It didn’t have a title, or lyrics, or vocals.

With precious time left to finish Automatic for the People at Seattle’s Bad Animals studio, singer and primary lyricist Michael Stipe had writer’s block. All that guitarist Peter Buck, bassist Mike Mills and drummer Bill Berry could do was wait for their bandmate to come up with … something.

As it was, the track that carried a working title of “C to D Slide” had endured a long process, beginning with practice/demo sessions that included the instrumental members of R.E.M. (i.e. everyone but Stipe). Although Buck, Mills and Berry all had defined roles in the band, they each played multiple instruments and in these formative gatherings, ideas could come from anywhere. In this instance, Berry – the drummer – had brought a melodic idea.

“Bill had this one chord change that he came in with, which was C to D like the verse of the song, and he said, ‘I don’t know what to do with that,’” Buck wrote in the liner notes of Part Lies, Part Heart, Part Truth, Part Garbage 1982-2011. “I used to finish some of Bill’s things … he would come up with the riffs, but I would be the finish guy for that. I sat down and came up with the chorus, the bridges, and so forth. … I think Bill played bass and I played guitar; we kept going around with it.”

As R.E.M. progressed in their work on their eighth album, the song was built up, too. Buck and Berry presented it to Mills and Stipe before it was recorded as a demo in February 1992 at John Keane’s studio in the band’s hometown of Athens, Ga. (with the singer humming in place of a lead vocal). In multiple recording sessions with producer Scott Litt in March and April at Bearsville Sound Studios in Woodstock, N.Y., R.E.M. piled layers and layers of sound onto the track.

Buck recorded acoustic guitar as the main element, then added a Rickenbacker electric (for the chorus), a Les Paul (for the “loud chords”), another Rickenbacker (“doing backwards strums” on the bridge) and a Telecaster (doing the slippery slide parts). He also played the mandolin-like bouzouki on the track – the same instrument that had served as the foundation for another Automatic selection, “Monty Got a Raw Deal.” Along with the drums, Berry played claves, which Buck felt brought “a nice little Brazilian accent” to the finished recording.

After time spent at Bearsville, R.E.M. recorded in Miami and Atlanta and then traveled to Seattle to finish the record in the summer, in time for an October album release. The instrumental components were done and dusted, but Stipe was still humming his part. The band thought the track was too good to leave off the album, but it wasn’t going to happen as an instrumental.

“I was under immense pressure to finish this one piece of music that the band loved,” Stipe remembered in Reveal: The Story of R.E.M. “We had already recorded an album’s worth of material and I had run dry. I didn’t feel capable of writing another song, and I just told the band, ‘Give me a couple of days walking round Seattle with my headphones on to see what comes.’ I wrote a walking song really, which is ‘Man on the Moon.’”

Watch R.E.M.’s ‘Man on the Moon’ Video

As Stipe walked, his mind began to race. Lyrics started to form, with words that evoked games (“Monopoly, 21, checkers and chess” – more hints of childhood, an album theme) and a sly contrast between men of science (Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin) and a man of faith (Moses). A crude Cleopatra joke about Elizabeth Taylor turned into a line about Egyptian snakes and Mott the Hoople made an appearance because, well, why not?

As the lyrics began to coalesce, the song’s central figure became Andy Kaufman, the fearless comedian and performance artist who had become a hero of Stipe’s when, as a teenager, he saw him on Saturday Night Live. “Man on the Moon” wasn’t just a tribute to a clever artist, but how Kaufman challenged the audience’s perception of what he was doing. That ran the gamut from wrestling women to doing wretched impersonations as “Foreign Man” – only to deliver a killer Elvis Presley impression.

In fact, Kaufman spent so much time subverting expectations that many of his fans didn’t believe the news when the comedian was reported dead, the result of cancer, in 1984. Just as some had held out hope that Elvis hadn’t died, but faked his death to escape the pressures of fame, Kaufman disciples guessed that the Taxi star’s end was just a ruse. The conspiracy idea ties into the chorus, a celebration of skepticism: “If you believed they put a man on the moon… / If you believed there’s nothing up his sleeve, then nothing is cool.”

On a side note, “Man on the Moon” features ideas that reference three celebrated stars who died young: Elvis, Kaufman and Kurt Cobain. However, the Nirvana frontman wouldn’t die by suicide until 1994. In 1992, Cobain had become good friends with Stipe, after long being an R.E.M. fan. The “yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah” motif was an in-joke, because Stipe had ragged on Cobain for having too many “yeahs” in Nirvana’s lyrics, especially in “Lithium.”

“I told Kurt that I was going to write a song that had more ‘yeahs’ in it than anything he’d written,” Stipe told MTV News.

With more than 50 “yeahs,” plenty of nods to disrupted expectation (“here’s a truck stop instead of St. Peter’s”) and “Andy goofing on Elvis” (complete with Stipe’s own, casual impression of the King), the lyrics to “Man on the Moon” were complete. And just in time.

“That came together literally on the last day of recording,” Mills told Stereogum. “We had the music all finished and we were all pushing Michael to get it done and he came in with all those great words and melodies on that last day of recording.”

“Man on the Moon” settled in the 10th slot on Automatic for the People and was determined to be the record’s second single, released on Nov. 21, a month and a half after the album came out. Even with its soaring, sing-along chorus, the curious lyrics and rustic feel of the track didn’t ensure that this was going to be a big hit for R.E.M. (especially in the midst of an alternative rock explosion). But “Man on the Moon” conquered rock radio, going to No. 30 in the U.S., No. 18 in the U.K. and becoming the band’s biggest hit to date in Canada at No. 4.

A black-and-white video directed by Peter Care (who also had done “Drive” and “Radio Song” for R.E.M.) only augmented the feeling of open space in the song – and helped its popularity with frequent airings on MTV. The clip showed a cowboy-hatted-Stipe wandering in the desert, doing his Elvis moves and hitching a ride with Berry, driving a big rig. The two wind up at a roadhouse where Buck is tending bar and Mills is shooting pool. As Stipe downs an order of fries, footage of Kaufman plays on TV and the bar’s denizens take over lip-syncing duties.

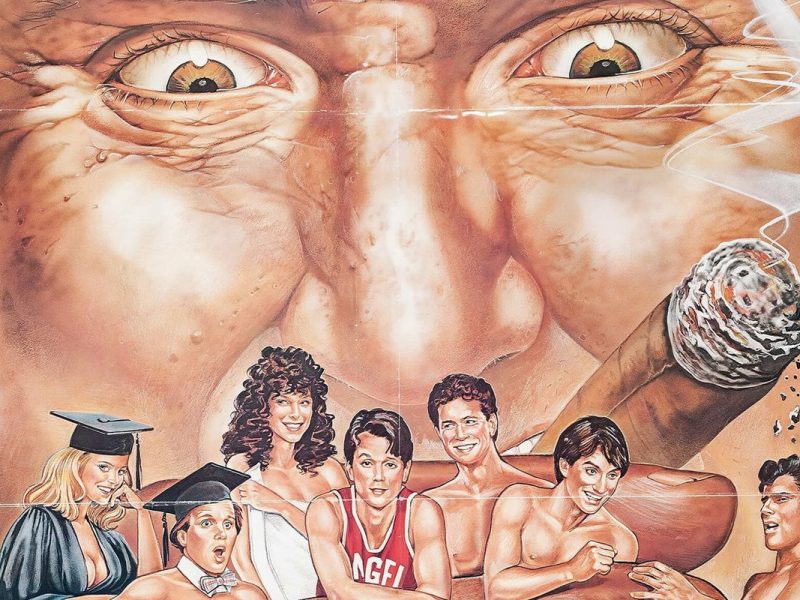

But “Man on the Moon” didn’t only inspire a celebrated music video, it also was central to a big-budget Hollywood movie. When Jim Carrey starred in a 1999 Kaufman biopic directed by Milos Forman, the film was titled after the song by R.E.M. The band also wrote “The Great Beyond,” among other soundtrack contributions, for the movie.

Watch R.E.M. Perform ‘Man on the Moon’ Live

Despite being a solid – but not blockbuster – hit single, “Man on the Moon” turned into one of R.E.M.’s best-known songs, appearing on any best-of compilation featuring their Warner Bros. era material. Its popularity was aided by the fact that the band would perform the song at just about every show they played in the years following the release of Automatic for the People. The live version pushed the moseying tempo and featured Stipe bellowing “Cooo-ol!” along with Buck’s stinging guitar turns and Mills’s backing vocal acrobatics. R.E.M. always seemed to have fun playing it, something Stipe made clear when the band broke up in 2011. The singer said that “Man on the Moon” was the hardest song to leave behind.

“Watching the effect of that opening bass line on a sea of people at the end of a show,” he told Rolling Stone about what he’d miss. “And that is an easy song to sing. It’s hard to sing a bad note in it.”

Easy to sing. Tough to write.

Top 100 ’90s Rock Albums

Any discussion of the Top 100 ’90s Rock Albums will have to include some grunge, and this one is no different.