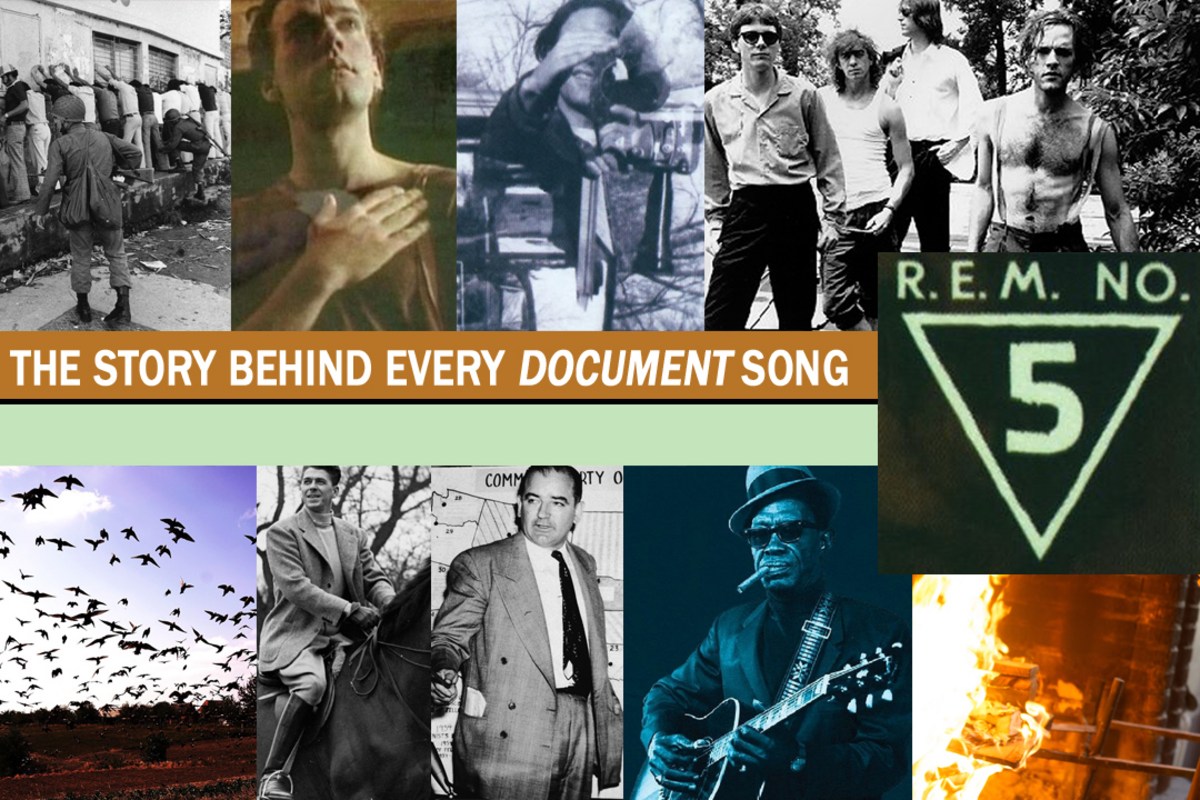

R.E.M.’s breakthrough 1987 album Document was the culmination of a few things: hard work, experimental tendencies and good old-fashioned trial and error.

On Document‘s predecessor, Lifes Rich Pageant, R.E.M. had brought in John Mellencamp producer Don Gehman to remove the murkiness that had categorized their first three records. Although Gehman was not brought back for the follow-up, Scott Litt built upon Gehman’s clarity, and the result was a radio-friendly sound that brought them into the Top 10 singles and album charts for the first time.

It helped that R.E.M. had delivered a collection of songs that matched the tenor of the times. Its first half reflected their anger at the previous six years of Ronald Reagan’s presidency. Beginning with an activist’s call-to-arms (“Finest Worksong”), they blended U.S. involvement in Central America (“Welcome to the Occupation”) with the return of right-wing political tactics (“Exhuming McCarthy,” “Disturbance at the Heron House”) before concluding that they were fine with the impending apocalypse (“It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine”).

But it was the second side where they kept up their experimental streak. Opening with a hit single (“The One I Love”), albeit the darkest, thorniest love song to reach the Top 10 since the Police’s “Every Breath You Take,” the rest of the album dealt with an 18th-century religious figure (“Fireplace”), the ability to predict earthquakes (“King of Birds”) and homelessness (“Oddfellows Local 151”).

Below are the stories behind each of the LP’s 11 songs.

“Finest Worksong”

Guitarist Peter Buck knew from the moment “Finest Worksong” was written that it would be the leadoff track for the album. The band’s newfound willingness to integrate more topical material into their music, without overdoing it, is on full display in this song.

Read More: ‘Finest Worksong:’ R.E.M. Gets Loud and Political, but Stays Weird

“Welcome to the Occupation”

“Welcome to the Occupation” was the third song Michael Stipe had written about the U.S. government’s intervention in South and Central America, but it was his most pointed so far. As the conflicts grew more and more violent, R.E.M. put their frustration into song: “Listen to the Congress / where we propagate confusion.”

Read More: R.E.M.’s Anger Comes Into Focus on ‘Welcome to the Occupation’

“Exhuming McCarthy”

In 1987, R.E.M. couldn’t help thinking that the times they were living in were eerily similar to previous politically tumultuous decades. “This is the kind of year Joe McCarthy would come back,” Buck told UPI at the time. “People would start hailing him. If he was still alive, he’d be a hero.”

Read More: How R.E.M. Took a Bite out of Dogma With ‘Exhuming McCarthy’

“Disturbance at the Heron House”

By Stipe’s admission, “Disturbance at the Heron House” was his take on George Orwell’s Animal Farm, a story of greed, hopelessness, deceit and arrogance. Orwell had intended for his book to be a comment on the Russian Revolution and the turmoil it created. To Stipe, the same ideas could apply to President Ronald Reagan’s administration.

Read More: R.E.M.’s ‘Disturbance at the Heron House’ Tackles Orwell and Reagan

“Strange”

The only cover on Document, “Strange” by Wire, appears almost squarely in the middle of the album. “Strange” had appeared on Wire’s 1977 debut, Pink Flag, which Stipe cited as a strong influence on his work.

Read More: R.E.M.’s Cover of Wire’s ‘Strange’ Speaks to the Moment

“It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine)”

A stream of lyrical consciousness delivered at breakneck speed, this apocalyptic musical manifesto has since become one of R.E.M.’s best-known tracks. Amongst the inspirations for the song? A strange party in which Lester Bangs hurled a one-off insult at Buck, Bob Dylan and a dream filled with birthday cake and jelly beans.

Read More: How R.E.M. Mixed Dreams, TV and Politics on ‘It’s the End of the World as We Know It’

“The One I Love”

Kicking off side two of Document, “The One I Love” stands in stark contrast to the preceding song. Despite its title, it’s a far cry from any traditional love song, which describes the subject as a “simple prop.” In 1987, Stipe swore to Rolling Stone that the song wasn’t about anyone in particular: “I would never, ever write a song like that.”

Read More: How R.E.M. Scored a Big Hit With the Brutal ‘The One I Love’

“Fireplace”

What do the Shakin’ Quakers have in common with R.E.M.? Maybe not much, but that didn’t mean Stipe couldn’t find some inspiration in their dancing method of worship. Also unique to this track is the contribution from saxophonist Steve Berlin, one of the first outside musicians to appear so prominently on a R.E.M. album.

Read More: Shakers and Saxophones Get Thrown Into R.E.M.’s ‘Fireplace’

“Lightnin’ Hopkins”

“Lightnin’ Hopkins” is not, as one might assume, a tribute to the late Texas bluesman. It’s much looser, more ambiguous than that. Stipe, at the time, was invested in the idea that art — and humanity in general — is often better off if it’s at least a little convoluted. “If you’re blasted into the public eye, you’re supposed to be one-dimensional,” he told The New York Times in 1987. “But I’m pretty big on people contributing to things that they take in – not just accepting them on face value.”

Read More: How R.E.M. Defied Easy Interpretation With ‘Lightnin’ Hopkins’

“King of Birds”

For many years, scientists have been studying the possibility that birds (and other creatures too) might be able to sense impending ecological disasters, including earthquakes. Precise conclusions for such a hypothesis are difficult to determine, but one such creature who also felt he could sense oncoming quakes was Stipe himself, who claimed he often got headaches just before earthquakes occurred. Hence, partial inspiration for “King of Birds.”

Read More: R.E.M. Ponder Earthquakes and Artistry on ‘King of Birds’

“Oddfellows Local 151”

Stipe knew the man dubbed Pee Wee in “Oddfellows Local 151,” a song that captures a small snapshot of the homeless crisis. It’s a bleak portrait, but it wasn’t that R.E.M was trying to be depressing — Stipe was simply finding it easier and easier to write truthfully about the things he witnessed around him. “Plus,” Mike Mills noted in 1987, “things are deteriorating to the point where he feels he should say something about it.”

Read More: R.E.M. Departs on a Fiery Note With ‘Oddfellows Local 151’

Top 100 ’80s Rock Albums

UCR takes a chronological look at the 100 best rock albums of the ’80s.