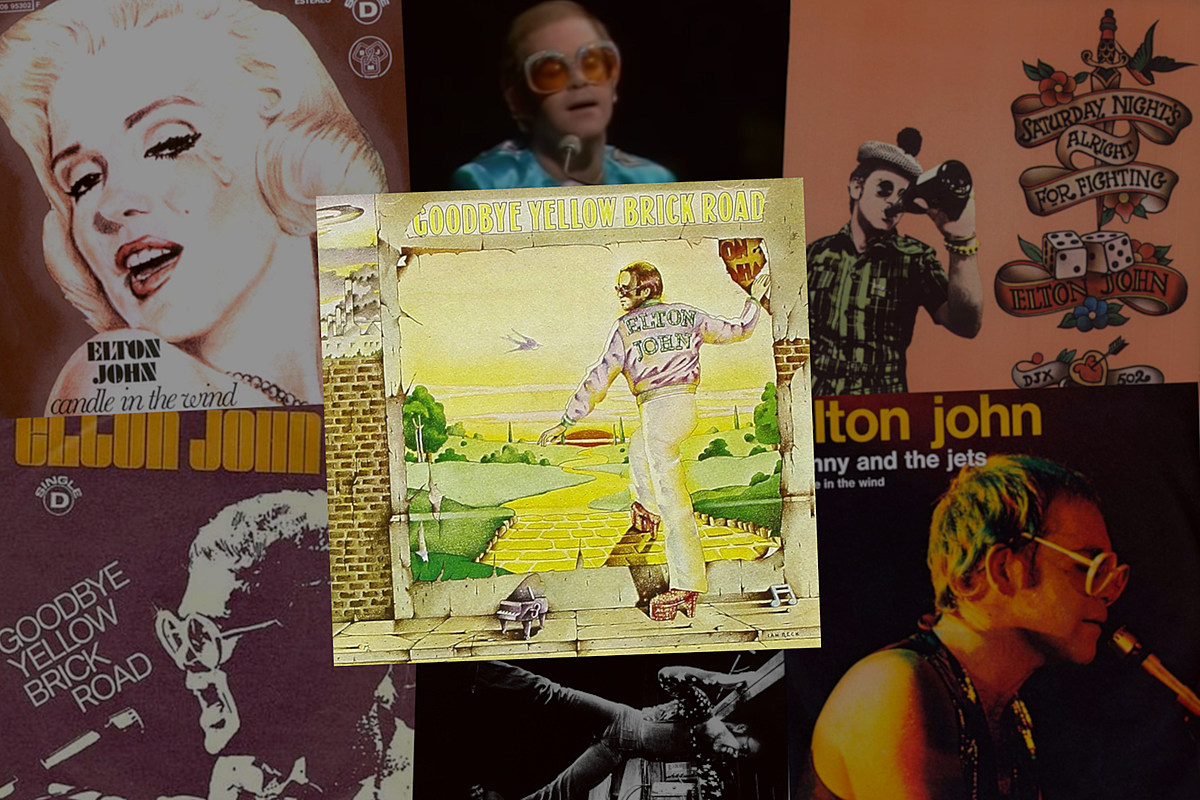

Elton John was already a success by the time he released his seventh studio album on Oct. 5, 1973. Still, the multiplatinum chart-topping Goodbye Yellow Brick Road elevated him from star to icon.

From front to back, the double album delivered some of the most impressive material of his career. Every element – from John’s creative dynamic with Bernie Taupin to the contributions of his backing band – was firing on all cylinders.

“It was a very exciting time in my life. It was a time that we had no fear, nothing was beyond us,” John reflected decades later to Rolling Stone. “It’s a wonderful thing the young have when they get on a roll. We were running on momentum and adrenaline. And then if you’re a talented enough artist, you find your place within the playing field. And this was our example of being at the height of our creative powers.”

READ MORE: How Elton John’s ‘Goodbye Yellow Brick Road’ Became a Masterpiece

Themes of fame, success and celebrity appeared throughout Goodbye Yellow Brick Road. Some critics called it a concept album, a term Taupin initially bristled over before later accepting.

“Maybe in retrospect, it subconsciously is a concept album because you’re just presenting all these characters in this sort of cinematic framework,” Taupin admitted on the BBC’s Classic Albums. “You’re bringing up Danny Bailey and Sweet Painted Ladies and Dirty Little Girls and they’re all part of this big sort of complex movie.”

Goodbye Yellow Brick Road is widely regarded as John’s magnum opus. It remains his most commercially successful album, having sold more than 20 million copies around the globe. Here’s a deeper look into all 17 songs on Goodbye Yellow Brick Road.

“Funeral for a Friend/Love Lies Bleeding”

Goodbye Yellow Brick Road is a soaring, cinematic triumph and its grand tone is immediately established with “Funeral for a Friend/Love Lies Bleeding.” Originally conceived as two separate songs, John discovered that they perfectly melded together into an emphatic cohesive piece. The first part, “Funeral for a Friend,” is a sweeping instrumental, designed as a kind of album overture with motifs from several songs heard later in the LP. Roughly five minutes in, Elton switches gears into “Love Lies Bleeding,” a propulsive tune inspired by the way a rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle can destroy a person’s relationships.

“Candle in the Wind”

One of the most famous songs in Elton’s repertoire comes next, the poignant “Candle in the Wind.” Though the song’s lyrics directly relate to Marilyn Monroe, it was designed as a broader commentary on the pitfalls of fame. “I think the biggest misconception about ‘Candle in the Wind’ is that I was this rabid Marilyn Monroe fanatic, which really couldn’t be further from the truth,” Taupin once noted. “It’s not that I didn’t have a respect for her. It’s just that the song could just as easily have been about James Dean or Jim Morrison, Kurt Cobain. I mean, it could have been about Sylvia Plath or Virginia Woolf.

“I mean, basically, anybody – any writer, actor, actress, or musician who died young and sort of became this iconic picture of Dorian Gray, that thing where they simply stopped aging,” Taupin continued. “It’s a beauty frozen in time. In a way, I’m fascinated with that concept. So, it’s really about how fame affects the man or woman in the street, that whole adulation thing and the fanaticism of fandom. It’s pretty freaky how people really believe these people are somehow different from us. It’s a theme that’s figured prominently in a lot of our songs, and I think it’ll probably continue to do so.”

“Bennie and the Jets”

When Taupin handed John the lyrics to “Bennie and the Jets,” he immediately decided what direction to head in. “I knew it had to be an off-the-wall type song, an R&B-ish kind of sound or a funky sound,” John told Rolling Stone. “The audience sounds were taken from a show we did at the Royal Festival Hall years earlier. The whole thing is very weird.”

Despite his enthusiasm for the track, Elton never envisioned it as a single and even fought his record label when they tried to put it out. He eventually relented when he was informed of how popular the song had become with Black listeners in Detroit. “And I went, ‘Oh my God,’” John recalled. “I mean, I’m a white boy from England. And I said, ‘Okay, you’ve got it.’ It just shows you that you can’t see the wood through the trees. To this day, I cannot see that song as a single.” “Bennie and the Jets” spent 18 weeks on the Billboard Hot 100, peaking at No. 1.

“Goodbye Yellow Brick Road”

The title track is sweeping and cinematic, evoking imagery of the classic Wizard of Oz. Lyrically, Taupin reflects his rise to fame from humble beginnings. “[The story of a] country kid going to the big city,” he said on Classic Albums. “But at the same time, yes, I think it could have been the all-encompassing world of fame. Could be rock ‘n’ roll – is it everything it’s cracked up to be? Possibly not.”

John’s vocals here are some of the most impressive of his career, as he jumps from his comfortable mid-range on the verses to high falsettos in the choruses. “A lot of people asked me if I sped the tape up,” producer Gus Dudgeon admitted, “but, in fact, it’s not sped up. It’s just the weird way that he decided to do it. That’s Elton.”

“This Song Has No Title”

In “This Song Has No Title,” what begins with minimalism opens to much more. The tune starts with just John’s voice and a piano, with only a soft woodwind initially joining the fray. But the chorus suddenly brings unexpected complexity, delivering layered harmonies, prog-rock-like chord changes and a fuller instrumentation. The result is mesmerizing.

“Grey Seal”

A track originally demoed for John’s self-titled second album, “Grey Seal” had been abandoned for a few years. He revisited it during the Goodbye Yellow Brick Road sessions and developed a different vibe for the song. Those early demos followed the type of piano-pop formula John used to perfection on tracks like “Honky Cat,” the Yellow Brick Road version was far more densely layered. A flurry of piano swirls through the lyrics, while an increased tempo adds frenetic energy. This version proves both upbeat and mysterious, making the finished version of “Grey Seal” decidedly more engaging than the initial concept. Decades later, fans got to hear the original take on Rare Masters, a compilation album released in 1992.

“Jamaica Jerk-Off”

John utilizes island motifs on this upbeat, poppy track. Lyrically, Taupin celebrates wild and exciting parties in tropical locales. Ironically, John’s experience in Jamaica was far from enjoyable. He’d originally planned to record Goodbye Yellow Brick Road in Kingston, a choice he made because the Rolling Stones completed Goats Head Soup there several months earlier. However, when John and his team arrived at the studio, there was no equipment and local recording staff were on strike. His group was also verbally harassed while walking in the neighborhood and found the whole environment quite unpleasant. They soon left and recorded in France instead.

In retrospect, some critics accused “Jamaica Jerk-Off” of cultural appropriation. John has insisted the song and its message were never intended to be insulting. “It’s about going to Jamaica and having a good time,” he told Rolling Stone. “It’s not about anything else. There’s no underlying message whatsoever.”

“I’ve Seen That Movie Too”

Few artists handle heartbreak as expertly as Elton. Here he delivers a soulful and personal portrait of a man confronting his unfaithful lover. Strings swell around the bluesy ballad, giving it further emotional gravitas. But it’s John’s vocals that drive the track, managing to somehow be strong yet vulnerable all at once.

“Sweet Painted Lady”

Leave it to Elton John to turn the story of a sailor frequenting prostitutes into something so charming. “Sweet Painted Lady” unfurls like a midtempo show tune, as he croons about a woman who is “getting paid for being laid.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, “Sweet Painted Lady” proved controversial, as radio stations refused to play the song due to its subject matter. Still, within Goodbye Yellow Brick Road – an album full of sexual themes – it fits in nicely.

“The Ballad of Danny Bailey (1909–34)”

Another character study, “The Ballad of Danny Bailey (1909-34)” tells the story of a criminal on the run who eventually gets gunned down by the law. “I don’t know if I’d seen a movie or read a book, but I came up with the first line, ‘Some punk with a shotgun killed Danny Bailey, in cold blood in the lobby of a downtown motel.’ And that was it,” Taupin told Rolling Stone. “It would have gone a number of different ways, but it ended up being a tune about a bootlegger. Again, it was one of those cinematic stories.”

“Dirty Little Girl”

Arguably the weakest point of Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, “Dirty Little Girl” still has plenty of redemptive values. The groove – propelled by Dee Murray’s funky bass line and Davey Johnstone’s crunchy guitar – is wonderful. Meanwhile, John’s distinctive piano and emphatic vocals match his backing band’s fire. It’s just that “Dirty Little Girl” does little to differentiate itself from the high-quality material found elsewhere on the album. Perhaps on another LP, it could have shined, or even been released as a single, yet on Goodbye Yellow Brick Road it tends to be forgotten. Put another way, when “Dirty Little Girl” is your album’s weakest song, you’re probably doing something right.

“All the Girls Love Alice”

Though not one of the album’s biggest hits, “All the Girls Love Alice” is one of the most analyzed songs on Goodbye Yellow Brick Road. The song tells the story of a 16-year-old girl who “couldn’t get it on with the boys on the scene.” Suggestions about Alice’s sexuality are rampant. At one point, she’s given a phone number and told to “wait ’til my husband’s away.” Later, Alice can be found getting her “kicks in another girl’s bed.” It’s generally accepted that the character was a lesbian, and possibly a prostitute: The lyric “come over and please me / Alice, it’s my turn” seems to hint at the latter.

Discussions about gender identity and sexuality were much more taboo at the time. Decades later, Taupin confessed he was amazed by the subject matters they covered within the album. Goodbye Yellow Brick Road was “all about weird situations, gay situations, straight situations, pornographic situations,” he admitted to Vulture. “‘All the Young Girls Love Alice,’ which has a line like, ‘two middle-aged dykes in a go-go,’ got played on the radio! I’m incredibly proud of the fact that we tested the waters and got away with things.”

“Your Sister Can’t Twist (But She Can Rock ‘n Roll)”

After striking gold with 1972’s “Crocodile Rock,” John once again indulges his inner ’50s rocker with “Your Sister Can’t Twist (But She Can Rock ‘n Roll).” John’s animated vocals and piano feel like they’re taken directly out of Little Richard’s playbook, while the backing vocals offer up a Beach Boys surf-rock vibe.

“Saturday Night’s Alright for Fighting”

Tapuin’s formative years were spent in English nightspots where he watched punks and mods regularly getting into dust-ups. Those experiences fueled “Saturday Night’s Alright for Fighting,” one of the most raucous tracks in John’s repertoire. To capture the frenzied nature of the tune, John recorded his vocals standing up and jumping around the studio – something he’d never done in the past. Still, the song’s not-so-secret weapon is Davey Johnstone, as his powerful guitar riff elevated “Saturday Night’s Alright (For Fighting)” to legendary status.

“Roy Rogers”

Taupin once again pulls from the imagery of his youth. He loved watching Westerns as a child, and Rogers was one of his favorite stars. John builds upon the nostalgia by utilizing country-inspired instrumentation, with unique two-part harmony used on the choruses and various points throughout “Roy Rogers.” “It’s interesting because when you think of the big vocal spreads that are on some of the tracks that I worked on, I noticed that in that one Elton only accompanied himself singing a line slightly ahead, a harmony with himself – which really personalized it,” the album’s orchestral arranger Del Newman later remembered. “It made it zoom in to just, you can imagine Roy Rogers the cowboy or Elton John the cowboy.”

“Social Disease”

Goodbye Yellow Brick Road came before John’s most public – and notorious – bouts of substance abuse. (He reportedly didn’t start using drugs until 1974.) So, “Social Disease” works as a kind of foreshadowing. Hidden within the buoyant song are lyrics tackling a dark subject: An alcoholic drinks all day and night, hitting the bottle to cope with the basic stresses of daily life. “I dress in rags, smell a lot, and have a real good time,” John sings during the chorus, reflecting how dependent and disorderly the character’s life has become.

“Harmony”

The epic journey of Goodbye Yellow Brick Road closes with this soaring ballad. On an album full of twists and turns, “Harmony” offers a measure of peace. “Harmony and me, we’re pretty good company. Looking for an island, in our boat upon the sea,” John sings, appropriately backed by emotive singers’ harmonies. Much like the “boat upon the sea” he mentions, “Harmony” feels like the triumphant end to a long journey: Goodbye Yellow Brick Road sailing into the sunset as the final notes play out.

The Best Song From Every Elton John Album

By conservative estimation, at least 10 of these Elton John LPs are stone-cold classics.

Gallery Credit: Matt Springer

Elton John’s Terrifying First U.S. Concert