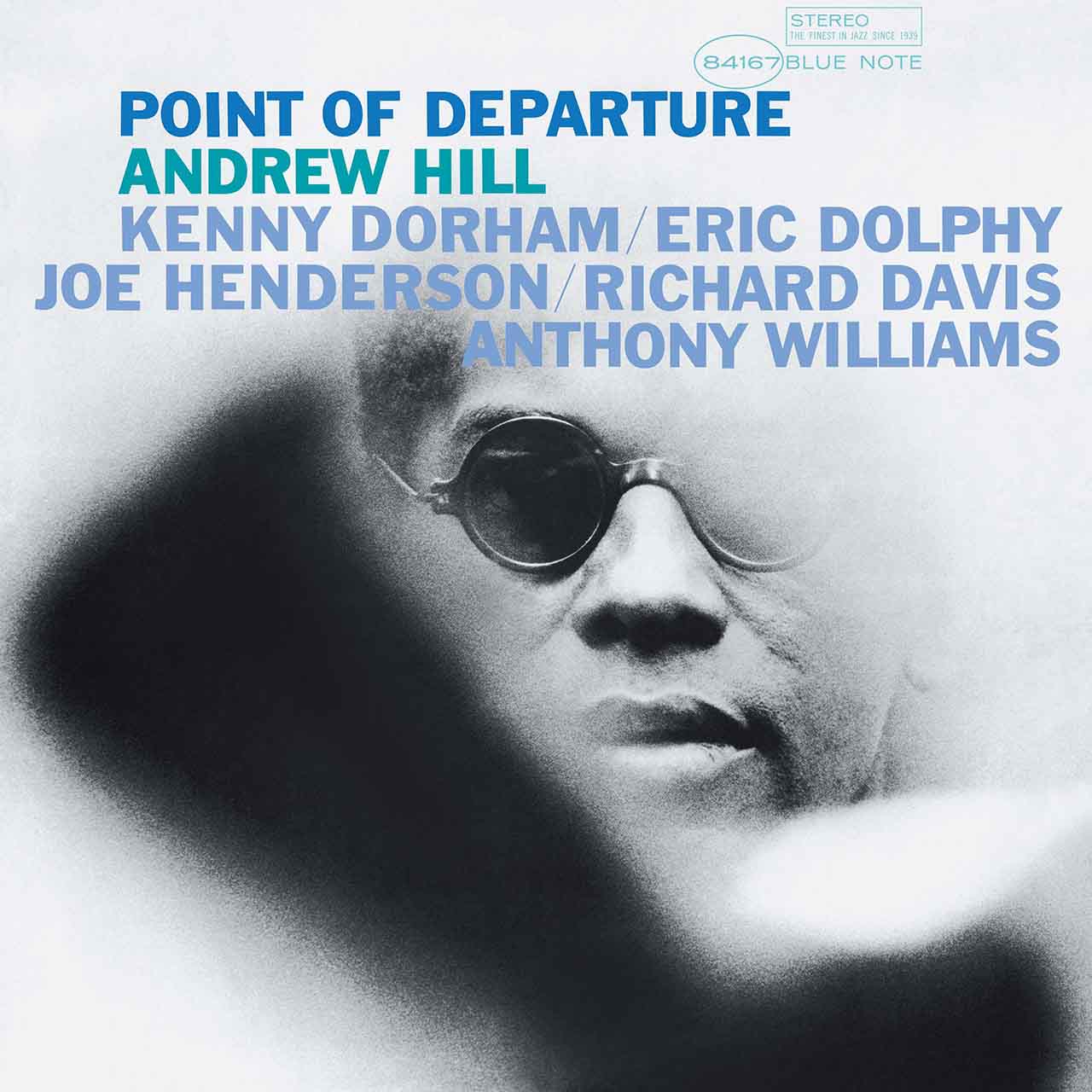

Blue Note’s co-founder Alfred Lion had a penchant for pianists who sounded different. In 1947, he signed Thelonious Monk, famed for his blend of dissonance and swing, and in the late 50s, recorded Herbie Nichols, another non-pareil pianist/composer. Given his track record, it was no surprise that Lion was drawn to Andrew Hill, who arrived in New York in the early 60s. A musical lone wolf stylistically beholden to no one, Hill carved out a musical niche not aligned with the hard bop, soul jazz, and free jazz movements that both defined and divided jazz at that time. Lion was intrigued by the pianist’s input on tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson’s 1963 LP Our Thing, and after hearing some of Hill’s compositions, promptly offered him a recording contract. Between 1963 and 1970, Hill recorded a dozen albums for Blue Note, though none were more highly regarded or influential than 1965’s Point of Departure.

Hill was one of modern jazz’s most original minds. To develop a uniquely personal sound, he stopped working as a sideman and even refused to listen to other people’s music. With Point of Departure, recorded in March 1963, he showed that his self-imposed musical solitude was paying dividends. While the public wasn’t yet fully aware of Hill’s accomplishments – his Blue Note debut album, Black Fire, wasn’t issued until April 1963 – many Big Apple jazz musicians were already in awe of him, which is probably why the pianist could assemble such a star-studded sextet for Point of Departure.

Listen to Andrew Hill’s Point of Departure now.

He brought in rising saxophone star Joe Henderson – adept at playing both hard bop and progressive jazz – alongside Eric Dolphy, a leading light of the avant-garde scene, who juggled alto sax with bass clarinet and flute. Curiously, Hill also hired a more conservative player, Kenny Dorham, a 39-year-old trumpet virtuoso with hard-bop affiliations. Rounding off the group were two forward-looking musicians who two months earlier had contributed to Dolphy’s yet-to-be-released classic Out To Lunch!: Bassist Richard Davis and a drummer almost half his age, eighteen-year-old wunderkind, Tony Williams, who had been playing with Miles Davis since 1963. Hill’s decision to blend youth with experience was inspired, allowing the session to reach forward while being tethered, albeit loosely at times, to the jazz tradition.

Beginning with “Refuge,” a long, blustery piece that sets Point of Departure’s distinctive post-bop tone, the album’s five tracks showcased Hill’s deeply chromatic style with its asymmetrical phrasing and emphasis on fractured rhythms. With its Thelonious Monk-like angular horn motifs and jaunty swing groove, “New Monastery” was easily the album’s most accessible cut. But perhaps the most affecting track was the album’s closer, “Dedication,” a slow, mournful elegy with hauntingly beautiful solos. “I wanted something that would fit a death march,” the pianist revealed in the liner notes, adding that the group’s performance deeply affected Dorham, bringing “tears to his eyes.”

Andrew Hill’s music was notoriously tricky to play – some of his Blue Note sessions were shelved because he was unhappy with how the music came out – but with Point of Departure, everything came together perfectly. Revered as an avant-garde touchstone, the album stands tall today as the Chicago pianist’s greatest achievement.

Listen to Andrew Hill’s Point of Departure now.