Beloved jazz composer and saxophonist Benny Golson passed away on September 21st. Though he was never a household name like his high school friend John Coltrane, Golson was one of the most accomplished tenor saxophonists and composers of the 1950s hard bop era, known for his smoky, muscular tone and for penning tunes like “Whisper Not,” “I Remember Clifford” and “Killer Joe” — songs that married indelible melodies with subtle harmonic sophistication.

During his seven-decade career, Golson’s pursuits varied: In the mid to late 50s, he played alongside golden-age jazz greats like Dizzy Gillespie, Art Blakey, and Quincy Jones, before co-leading a hard bop group called the Jazztet in the early 1960s; in the late 60s and early 70s, he worked as an arranger for some of the biggest names in pop music, like Eric Burdon & The Animals, Diana Ross, and Mama Cass Elliott—then moved to Hollywood to pursue work as a soundtrack composer. Judging from the 38 solo albums and 300 songs he amassed before his retirement in the late 2010s, though, his love for haunting melodies and ear-catching chord sequences never wavered—even when it flew in the face of fashion, such as during the avant-garde jazz craze of the 1960s. “Melody is so important to me,” he told jazz writer Anthony Brown in 2009. “I always felt like (a song) should have some melodic content, something that’s memorable, something that has the possibility of living past my time.”

Collaborators admired him for his composing and arranging abilities and his nuance as a performer — fellow saxophonist Sonny Rollins called him “a jazz man supreme.” But they also remembered him as an erudite, highly articulate man with an extensive vocabulary. “Boy, you better have a dictionary when you speak with Benny,” Jones, who invited Golson to join his big band in the late 1950s, joked in 2010, speaking to the Tune into Leadership website. The saxophonist’s flair for language was on full display in his memoir, Whisper Not: The Autobiography Of Benny Golson, which he wrote with Jim Merod in 2016 and was named Best History Book by the Association for Recorded Sound Collections.

Golson was born in Philadelphia on January 25, 1929. An only child, he was brought up by his mother, Celadia, a seamstress and amateur singer who encouraged her son’s musical inclinations from an early age. At nine, he started taking piano lessons. “I thought I was going to be a classical pianist and practiced assiduously,” he told Record Collector in 2009.

Golson’s aspirations changed dramatically at 14, when he heard tenor saxophonist Arnett Cobb play a raucous, bluesy solo on Lionel Hampton’s swinging big band jazz record, Flying Home No. 2. “From that moment the piano immediately began to pale,” Golson recalled to Record Collector. “My mother got me a saxophone and during the summer I [practiced] in the living room and drove everybody on the block crazy.”

Golson’s new obsession brought him into the orbit of another young enthusiastic hornblower at his high school: John Coltrane, who was two years his senior. Bonding over their shared admiration for swing-era alto sax star Johnny Hodges, the two became fast friends and began practicing together at Golson’s home. “We were together every day,” Golson told Record Collector. “We went to jam sessions together and played jobs that we didn’t get paid for. We had heartaches, rewards, and tragedies but it was great. We went through a lot together.”

In 1947, Golson decamped to Washington DC to study music education at Howard University. After two and a half years, the clubs beckoned, and he dropped out to pursue music full time. Following a brief stint playing with local jazz guitarist Tiny Grimes, he got a gig playing back-up for R&B singer and saxophonist Bull Moose Jackson. One of the players in Jackson’s band was noted bebop pianist and composer Tadd Dameron, who noticed Golson’s way with melody and encouraged him to write music. “Whatever progress I made [as a composer] is owed to Tadd,” the saxophonist would tell JazzWax in 2008. “He was so melodic and a great mentor.”

In the early 1950s, Golson’s growing notoriety as an uncommonly versatile sax player — one who felt equally at home playing big band swing as he did improvising in a bebop setting — saw him appearing alongside some of the biggest names in the East Coast jazz scene, including young hard bop trumpet star Clifford Brown, big band vibraphonist Lionel Hampton, and R&B hornblower Earl Bostic. By the middle of the decade, he had also started getting attention as a composer. His big break arrived in 1955, when Miles Davis recorded a version of his sinewy hard bop number “Stablemates” for his album Miles: The New Miles Davis Quintet — on the recommendation of John Coltrane, who had recently joined the group.

“Miles Davis validated me, brought me to the attention of people through him being an icon,” Golson told Jazz Journal in 2019. “That’s where my career as a writer took off. I’ve never been out of work since.”

In 1956, he began a two-year stint playing alongside bebop trumpet legend Dizzy Gillespie, whose love for intricate chromatic melodies and unusual chords had a profound influence on the saxophonist. “He changed my thinking,” Golson would tell Jazz Wax. “The things he showed me musically were a revelation.” It was while he was with Gillespie that Golson wrote two of his most famous songs: “Whisper Not,” an instrumental with a silky, caressing melody, and the slow, plaintive “I Remember Clifford”— an elegy for his collaborator Clifford Brown, who died in a car crash in 1956. “The song took me the longest of any song I ever wrote — two complete months — because I wanted it to be the embodiment of what Clifford Brown was as a trumpet player and as a dear friend,” he told Record Collector. “I wanted the notes to represent him.”

In 1958, the year after he moved to New York, Golson joined the Jazz Messengers, a group led by the powerhouse hard bop drummer Art Blakey. Golson was only meant to play for one night, deputizing for Jackie McLean, but he ended up spending a year with the group — an experience that would start shaping his playing style on his own records, beginning with the album, Gettin’ With It, recorded in late 1959 for Prestige’s New Jazz imprint. “He was the best drummer I’ve ever worked with but I had great trouble adapting to his style at first,” he told Record Collector. “I came in with a mellifluous and flowing sound and he was bashing away. He forced me to play louder and in a different way.”

Golson’s time with the Jazz Messengers was a fruitful one for his writing career. As the band’s musical director, he contributed three memorable tunes to the group’s classic 1958 Blue Note album, Moanin’. One of them was the driving “Blues March,” a showcase for Blakey’s virtuosic drum skills with a catchy melodic theme and driving, martial backbeat. Another was “Along Came Betty,” an urbane slow-swinger with a sinuous, harmonized horn melody. Both songs would become part of the standard jazz canon, recorded by acts as varied as the Quincy Jones big band, soul jazz trio The Three Sounds, and Latin jazz vibraphonist Cal Tjader.

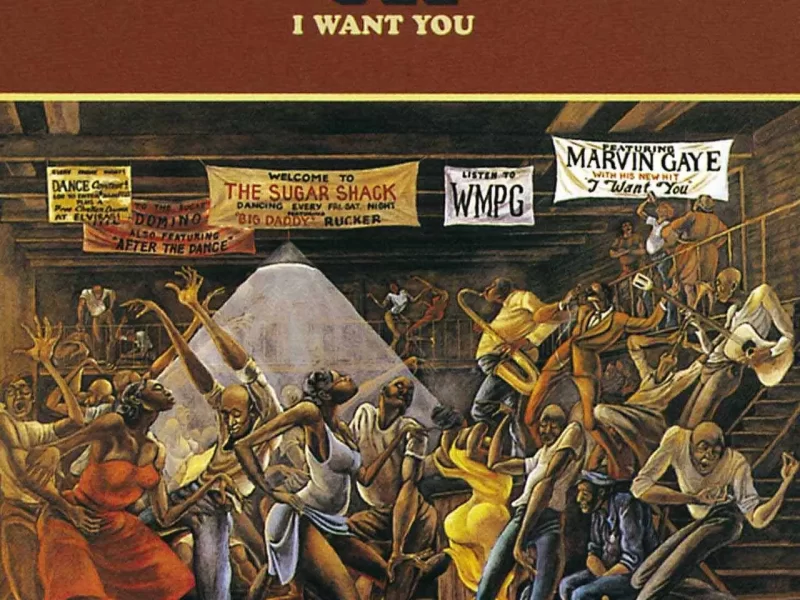

In 1959, hoping to expand his musical horizons, Golson joined forces with trumpeter Art Farmer and launched The Jazztet, a six-piece whose three horns proffered a richer, more textured sound than most other hard bop combos. The group’s 1960 debut LP Meet The Jazztet, on Chess Records’ Argo imprint, included a Golson-penned number called “Killer Joe,” combining a cool, insistent groove with a slow, seductive melody. “Playing Birdland I used to see the pimps come in with a lady on each arm,” he told Record Collector, explaining the tune’s inspiration. It would eventually be known as Golson’s signature song — especially after it became the basis for a 1970 hit single by Quincy Jones, then a noted pop and R&B record producer.

Golson was busy in the first half of the 60s, both as a leader and sideman. But in 1967, frustrated with what he perceived as a lack of opportunities for artistic growth, he decided to take a break from the New York jazz scene. On the encouragement of Jones, he moved to Hollywood, hoping to establish himself as an arranger and composer. “I was turning down work as a saxophonist, because I didn’t want to be known as a jazz musician,” he told Anthony Brown in 2009. “I wanted to be a film composer.”

In 1969, Golson scored a coming-of-age film called The Learning Tree, directed by future Shaft director Gordon Parks. During that time, he was also writing music for commercials and working at Universal Studios, where he penned music for several well-known TV shows, including Mission: Impossible, M.A.S.H., and Six Million Dollar Man. “While all this was going on, Benny Golson, jazz musician, got lost,” he would tell jazz critic Les Tomkins in 1983. “For eight years I never even opened my saxophone case.” Early on in his time in Los Angeles, he also became a Jehovah’s Witness. He would remain one until the end of his life.

After 12 years on the West Coast, Golson returned to New York and resumed his recording career, cutting a couple of disco-funk albums for Columbia in the late 1970s and producing some R&B records by Esther Phillips and Larry Graham & Graham Central Station. In the 1980s, Golson returned to his hard bop roots and resurrected The Jazztet, though picking up where he left off wasn’t without a struggle. “The road to regain my full jazz confidence was long and hard,” he wrote in his 2016 memoir. “I had to relearn many skills I once took for granted.”

Golson enjoyed a moment of wider fame when he played himself in Steven Spielberg’s 2004 movie, The Terminal, which identified him as one of the last surviving musicians of a group of 57 jazz artists who appeared in the iconic 1958 Esquire photograph, “A Great Day In Harlem.” During the last two decades of his life, he was also the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and an NEA Jazz Master fellowship, in addition to honorary degrees from Berklee College of Music, Howard University, and the University of Pittsburgh.

Golson continued touring and recording into his late 80s, splitting time between New York, Los Angeles, and Friedrichshafen in Germany. He released his final album, Horizon Ahead, in 2016 for the High Note label. It was full of wistful, aching melodies, and though he was 87 at the time, his saxophone playing was just as lyrical and athletic as it had always been.

While Golson’s accomplishments as a saxophonist were eclipsed by the more experimental exploits of contemporaries like Rollins and John Coltrane, his peers admired his playing for its soulfulness. Mostly, though, he will be remembered as a songwriter who gave modern jazz some of its most durable melodies. Describing his approach in a 1983 interview with the National Jazz Archive, Golson emphasized authenticity as his abiding ethos as composer: “I have to write what I feel in my heart,” he said. “I can’t write to please the people. It’s got to be what I feel; otherwise it would be all for naught — it would be a lie. I’ve got to be fair to myself.”