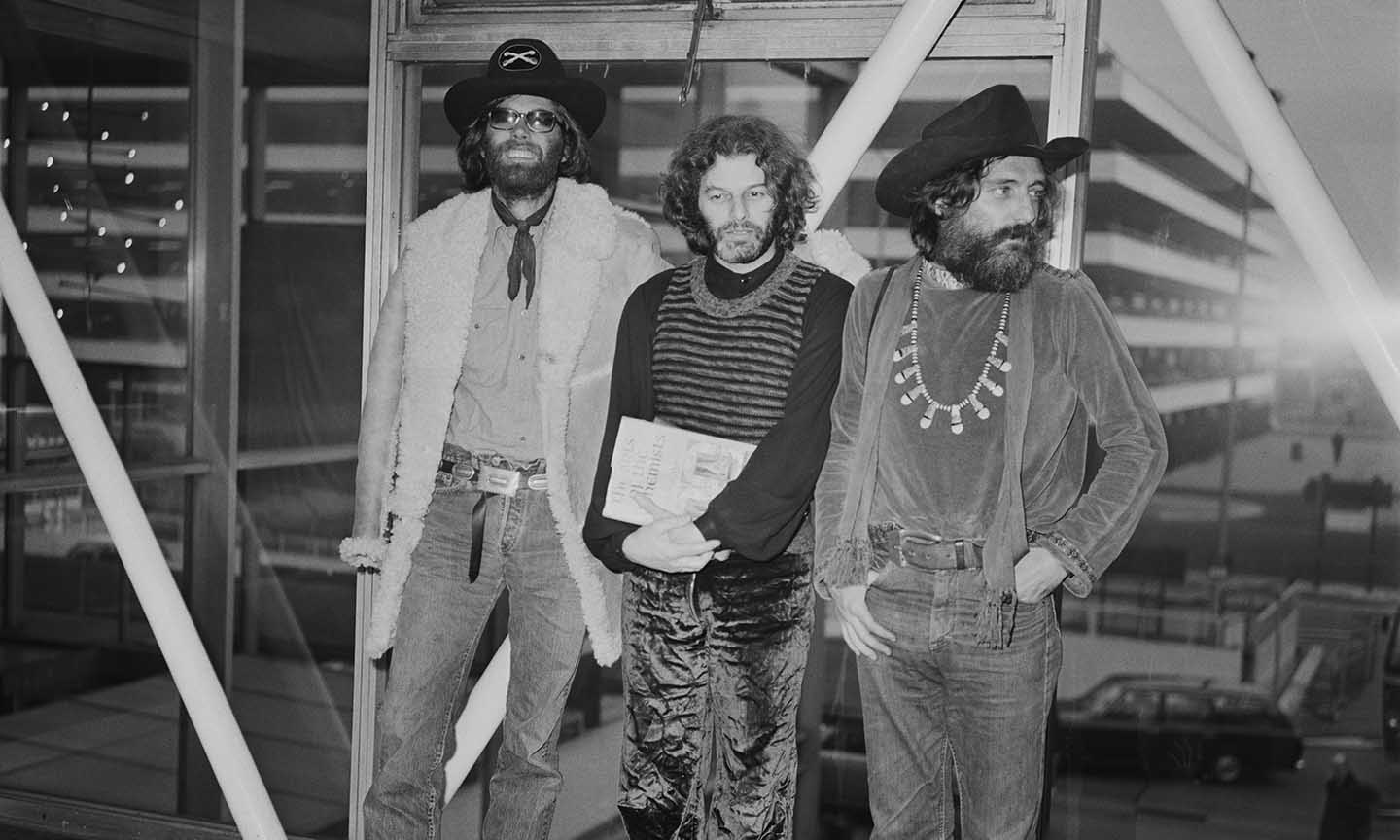

Henry Fonda, Alejandro Jodorowsky, and Dennis Hopper in 1971 Photo: George Stroud/Daily Express/Getty Images

There are few directors as revered in the world of counter-cultural filmmaking as Alejandro Jodorowsky. The Chilean-French filmmaker’s phantasmagorical movies are thought-provoking, absurd, energetic, and vivid feats of imagination, rich with religious and occult symbolism. They are unlike anything else in cinema. Jodorowsky’s use of music is intrinsic to their appeal, with his soundtracks earning the cult status enjoyed by his work. The world of music loved Jodorowsky back, with musicians playing a key role in the making of his films and many generations citing the filmmaker as an influence.

Born in Chile in 1929, Jodorowsky worked as an actor and a circus clown early in his life and, by 1953, he was writing material for famed mime artist Marcel Marceau’s troupe in Paris. On relocating to Mexico, Jodorowsky began directing plays and co-founded the “Panic Movement,” an art collective delighting in rebellious and disruptive acts known as “happenings.”

Listen to the El Topo and The Holy Mountain soundtracks now.

Jodorowsky’s debut movie, Fando And Lis (1967) was so provocative it caused a riot at its Acapulco Film Festival premiere and was banned in Mexico. His follow-up, the surreal and symbolism-heavy “acid Western” El Topo was released three years later and became an unlikely hit. It was shown exclusively at The Elgin Cinema in New York City in a late slot and word spread of the movie’s mind-expanding properties. John Lennon and Yoko Ono were among its fans and were instrumental in spreading the word. “I was so lucky, because Yoko Ono was a conceptual artist and they were very interested in intellectual and spiritual things,” Jodorowsky recalled in 2007. “John Lennon told his manager [Allen Klein] to give me $1 million to do whatever I would like to create next.” Klein’s company ABKCO bought the rights to El Topo and he co-funded Jodorowsky’s next movie, The Holy Mountain.

Klein was at the helm of the Beatles-founded Apple Records at the time and the El Topo score – composed by Jodorowsky himself with Nacho Méndez, a collaborator from his Mexican agit-prop days, and featuring additional music and production gloss from John Barnham (George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass orchestrator) – was released on the label in 1971. Jodorowsky’s music flits between skewed and lo-fi takes on spaghetti western themes (“Bajo Tierra (Under The Earth)”), eerie instrumental pieces built around distorted electric guitar (“La Catedral De Los Puercos (The Pigs Monastery)”), hypnotic flute cues (“El Agua Viva (Living Water)”), and moments of elegance and beauty (the sweeping strings of “Entierro Del Primer (Burial Of The First Toy)” and the bucolic “Topo Triste”).

In 2007, Jodorowsky told cult movie magazine Electric Sheep how the El Topo score came together, “I had a person who played the flute. I took a piece by Bach for instance, and I took scissors and cut it and re-arranged the pieces in another order and then I made the guy play it on the flute… There was another idea that I called ’21 Friends’. I gave a musical note to my friends, do re mi fa sol la si, and then I asked them to come to my house and I was noting the order they were coming, and I made music from that… I was inventing ways to make music.”

The filmmaker went on to emphasize the importance of music to his filmmaking, “I always think that I’m making musical pictures. But not musicals as you see here in the theatre. They call them musicals but they’re not, they’re just stories in which they put songs and dance. For me, a musical is a construction in which images and music go together. The music is always sacrificed in movies; it just accompanies the story in order to produce subliminal sensations in the audience. You need to forget the music. Every time a man and a woman look into each other’s eyes you have the music, na na na, or they’re killing someone, boom boom boom, you have a strong rhythm. But that is not a musical. What I do is different. The music speaks as much as the image. It doesn’t accompany it; they’re both part of the creation together.”

Released in 1973, The Holy Mountain was Jodorowsky’s masterpiece, a vivid and hallucinatory spiritual quest peppered with mind-boggling imagery. The soundtrack was just as groundbreaking, Jodorowsky later describing it as, “Another kind of music – something that wasn’t entertainment, something that wasn’t a show, something that went to the soul, something profound.”

The movie was scored by free jazz trumpeter Don Cherry (who had previously collaborated with John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, and Sun Ra), multi-intrumentalist, composer, and arranger Ronald Frangipane (keyboards on hit films Barbarella and Midnight Cowboy, as well as The Archies’ 1969 hit, “Sugar Sugar”), and Jodorowsky himself. The varying backgrounds and sensibilities of the composers resulted in a smorgasbord of genres – spiritual jazz, primitive techno, lush classical, sci-fi sound effects, psychedelic rock, becalming ambient sounds, and much more – interweaving in a sonic collage that echoed the rampant creativity of the movie.

Jodorowsky took a hands-on approach to the soundtrack, as he told Electric Sheep, “Some noises I had to make myself. Nobody knows that but I made a lot of sounds. When the thieves attack the masters in The Holy Mountain, I had a piano and I took a chamber pot and I started to hit the piano with the chamber pot. It was fantastic, the chamber pot made a fantastic sound!… And I worked with a fantastic jazz musician called Don Cherry… He brought lots of musicians. One time I had 100 guys! He made the music as he was watching the picture. Every time I discovered ways to make the music I needed.”

The director also turned down a former Beatle for a role in the movie, as he later told Dazed & Confused magazine, “George Harrison wanted to play the thief. I met him in the Plaza Hotel in New York and he told me there’s one scene he didn’t want to do, when the thief shows his a**hole and there is a hippopotamus. I said: ‘But it would be a big, big lesson for humanity if you could finish with your ego and show your a**hole.’ He said no. I said, ‘I can’t use you, because for me this is a sin.’”

A year after The Holy Mountain’s release Jodorowsky and Klein fell out after the director walked out on the studio’s next movie, The Story Of O. The disagreement led to a decades-long feud. This meant the complete score to The Holy Mountain remained unreleased until 2007. During its time in the wilderness, the score became a thing of near-mythological intrigue among jazz fans, soundtrack collectors, and musicians. Its vinyl reissue – along with El Topo – will ensure future generations fall under its transformative spell.

Listen to the El Topo and The Holy Mountain soundtracks now.