In 1990, Elton John sat across from Hugh Williams, his partner at the time, at a rehab center where Williams had gone for treatment for drug addiction. Williams’ counselor had instructed each man to make a list of things they didn’t like about one another and then had them read those lists aloud. In his 2019 memoir, Me, John recalled his list of gripes about Williams was short and minor: He was untidy, left his clothes everywhere and wouldn’t put his CDs away when he finished playing them. Then it was Williams’ turn to read his list about John.

“I noticed he was shaking,” John recalled. “He was more terrified than me. ‘You’re a drug addict,’ he said. ‘You’re an alcoholic. You’re a food addict and a bulimic. You’re a sex addict. You’re codependent.'”

John could not deny these things. He was a mess and a very public one at that. His years in the wasteland of cocaine and alcohol left him veering between manic episodes and inexplicable rages, and the addition of the binge-and-purge nature of bulimia had a ravaging effect on his body. You can see the result of the totality of his addictions in the film of him performing “Skyline Pigeon” at the funeral of teenage AIDS victim Ryan White: a bloated, pale, frightening figure at the piano.

“When I saw the footage of the funeral,” John told the Los Angeles Times, “I thought, ‘My God.’ I was so fat, so old.”

Shortly after he met with Williams and the counselor in July 1990, John checked into Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Ill. (a suburb of Chicago), to treat his alcohol, drug and food addictions, all at once. “I didn’t want them treated consecutively,” he wrote in Me, “which would have meant spending something like four months going from one facility to another.”

The six weeks he spent at Lutheran General provided him with education about himself, not just his addictions. Compelled for the first time in his adult life to perform modest tasks like making his bed and washing his clothes, John balked, as much out of confusion over how to take care of himself as embarrassment over being ordered to do so.

“I tried to run away twice because of authority figures telling me what to do,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “I didn’t like that, but it was one of the things I had to learn – to listen. I packed my suitcase on the first two Saturdays and I sat on the sidewalk and cried. I asked myself where I was going to run: ‘Do you go back and take more drugs and kill yourself, or do you go to another center because you don’t quite like the way someone spoke to you here?’ In the end, I knew there was really no choice. I realized this was my last chance.” Ultimately, the attitude adjustment and physical detoxification proved life-changing.

“I came out of rehab and, you know, it’s astonishing when you think of the chain of events,” John told Rolling Stone. “Everything came alive again. The hope. Everything. Music never left my side.”

Listen to Elton John’s ‘The Simple Life’

Still, he was not ready to go back to work quite yet. “I flew back to London,” he recalled in Me, “where I called in at [the management] office and told everyone I was taking some time off. No gigs, no new songs, no recording sessions for at least a year, maybe 18 months.”

(He did make one exception, which he mentions in his memoir: “unexpectedly turning up onstage in full drag at one of Rod Stewart’s Wembley Arena gigs and sitting on his lap while he tried to sing ‘You’re in My Heart’ … Spoiling things for Rod has never felt like work, more a thoroughly enjoyable hobby.”)

John lived alone for much of his time away; he got a dog, and the two could be spotted walking around London by themselves. He also attended Alcoholics Anonymous meetings – sometimes three or four a day.

“It was wonderful, the way they just accepted me,” he told biographer Philip Norman in Rolling Stone. “They didn’t care who I was. For the first time in 20 years, I could feel totally anonymous. The incredible thing about AA is that, whatever your addiction has made you do, there’s never any blame, only sympathy and love.”

While John was spending restorative time out of the spotlight, he still mattered to his fans. A career-spanning box set, To Be Continued … , was released in the U.S. in November 1990, and a tribute album of his and collaborator Bernie Taupin’s work, Two Rooms: Celebrating the Songs of Elton John & Bernie Taupin, came out 11 months later. More incredibly, George Michael released a version of John’s 1974 hit “Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me,” recorded live at Wembley Arena in spring 1991 with John joining him as a special guest. The duet topped the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart in February 1992.

Armed with a cache of new songs he’d written with Taupin, a rejuvenated Elton John walked into Paris’ Studio Guillaume Tell in November 1991, and almost immediately turned around and walked out.

“He had had a lot of fear going in to make the album because he hadn’t made an album sober [in some time],” John’s manager John Reid told the Los Angeles Times. “We went into the studio the first day, and he lasted about 20 minutes and he said he couldn’t do it.”

“I was used to making records under the haze of alcohol or drugs,” John told Rolling Stone, “and here I was, 100 percent sober, so it was tough.” “He just wasn’t ready,” Reid noted, “but we went back the next day and eventually it was fine. The album just flowed.”

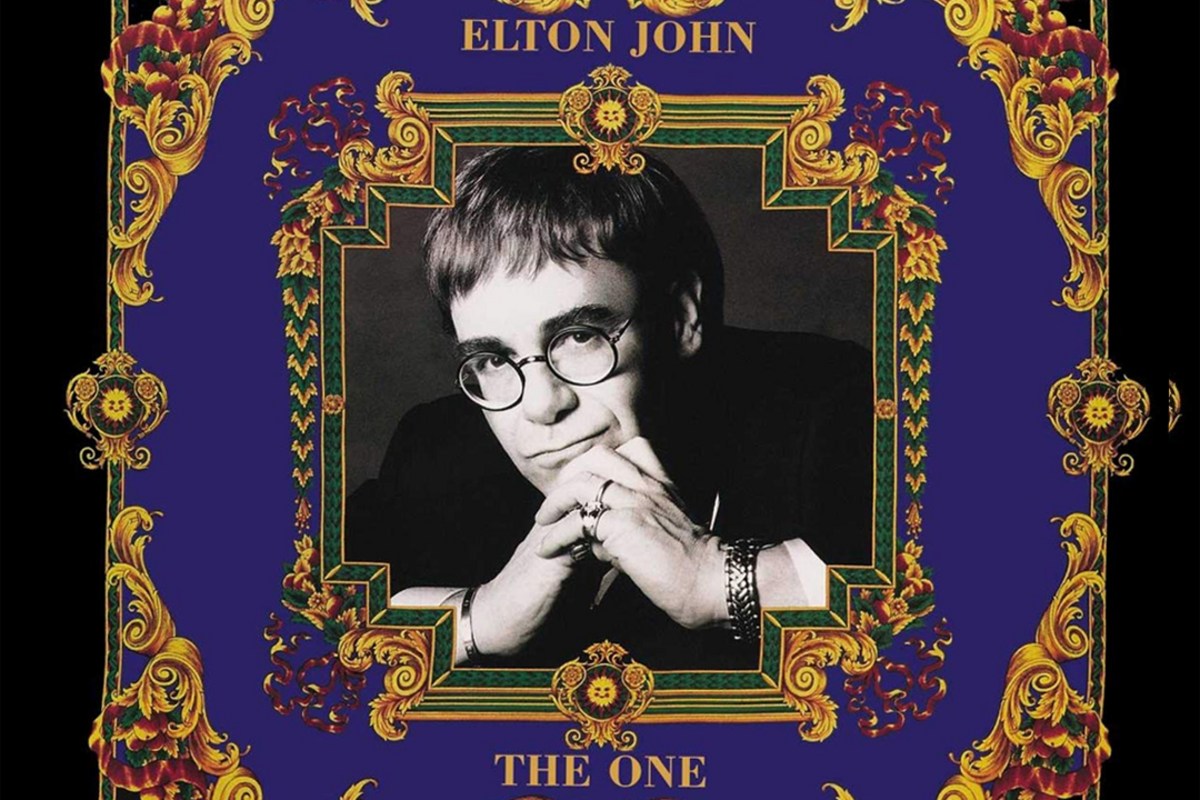

That album was The One, released June 22, 1992 – Elton John’s first new studio album in three years and the centerpiece of a massive 13-month world tour that would find him playing more than 150 shows. The record kicks off with the midtempo “Simple Life.” The sound of the song is completely contemporary – Olle Romo’s electronic percussion and Pino Palladino’s supple fretless bass work provide the foundation, while atmospheric keyboards hold firm under a synthesizer with a harmonica sample that establishes the melody. John’s voice is strong as he delivers Taupin’s defiant lyrics, particularly in the chorus: “And I won’t break and I won’t bend / And with the last breath we ever take / We’re going to get back to the simple life again.”

“Simple Life” segues into the title track, which also served as the album’s first single. A big, dramatic piano ballad, “The One” was a perfect complement to John’s duet with George Michael on “Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me” – perhaps a peek at the same character’s life, 18 years after his first appearance on record. Taupin’s lyrics capture a moment of contemplation – a private moment given Biblical size and emotional heft: “For each man in his time is Cain / Until he walks along the beach / And sees his future in the water / A long, lost heart within his reach.”

Watch Elton John’s ‘The One’ Video

Similar to “The One” in sound and tempo, “The North” presents a different kind of moment – a departure from home and people who have mistreated the character to whom John gives voice. As he leaves the space, he leaves his pain behind (“The North is my mother / But I no longer need her”).

When asked by Rolling Stone to list 20 of his songs that described his life, John included the song saying, “‘The North’ I love a lot; that’s my favorite song [on The One] without question.”

John’s friend Eric Clapton shares the mic on “Runaway Train,” which became the album’s second single. Both singers are in fine voice, but their respective instrumental performances are what make the song special – Clapton’s guitar, in particular, sears anything in its path, cutting through the bed of synthesizers that permeates the song. John’s organ accents and solo likewise provide an analog antidote to the production sheen. “Understanding Women” features another guitar hero – Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour – adding some fire to proceedings. Taupin’s lyrics on this one are, to be honest, little more than a long exasperated sigh (“Some men reach beyond the pain / Of understanding women”), but Gilmour’s solo is well worth sitting through the exhalation to hear.

The One ends with “The Last Song,” a stunning ballad presenting a young man dying of AIDS who is reunited with his estranged father in his last moments. Taupin’s lyrics (“I can’t believe you love me / I never thought you’d come”) are heartbreaking and proved troublesome for John to get through in the studio.

“Bernie’s lyrics … were beautiful, but I just couldn’t cope with singing them,” John wrote in Me. “It was just after Freddie [Mercuy]’s death. Somewhere in Virginia, I knew [former partner] Vance Buck was dying, too. Every time I tried to get the vocal down, I started crying.”

“The Last Song” was used in a montage at the conclusion of And the Band Played On, a docudrama on the early days of the AIDS crisis, based on the book by Randy Shilts. The sequence featured photos and videos of prominent individuals who had died from AIDS. “Half of them were people I knew personally,” John wrote.

The One launched Elton John back to the top tier of pop performers, becoming his first Top 10 album in the U.S. since Blue Moves in 1976. Within two years, he would help pen and perform the soundtrack to the Disney film The Lion King and return to the top of the album and singles charts, completing the comeback begun by his sobriety and the songs on The One.

Elton John Albums Ranked

Counting down every Elton John album, from worst to best.