Stardom was never on Bonnie Raitt’s radar. From the beginning of her career, she was mostly concerned with the craft of live performance.

“I personally don’t have any ambition to be any big hot stuff,” she told Sing Out! in 1972. “I like to play. I could play second act, or play at Jack’s [a bar and music venue] in Cambridge for the rest of my life. And that’s what I’m trying to do now, to build a base on live appearances rather than on records.”

She took to music from a young age, with parents who encouraged her interests. Raitt’s mother was a pianist and her father was a musical-theater actor who appeared in productions of Oklahoma! and The Pajama Game. Raitt first began to hone her skills on guitar while still a teenager at summer camp, then as a young adult on the campus of Harvard, where she majored in social relations and African studies.

In Cambridge, she met Dick Waterman, a leader of the then-growing blues revival movement. Not long after, she decided to leave school and move with him to Philadelphia. She began performing there locally, as well as in Cambridge and New York City. “It was an opportunity that young white girls just don’t get,” she recalled in 2002, “and as it turns out, an opportunity that changed everything.”

A 1970 at the Gaslight Cafe found Raitt opening for John Hammond Jr., son of the legendary Columbia Records executive. The New York City venue was once a haven for up-and-coming folk artists like Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell, but was then turning its ear toward blues. Word began to spread about the exceptionally talented young guitarist, whose slide work in particular stood out from others.

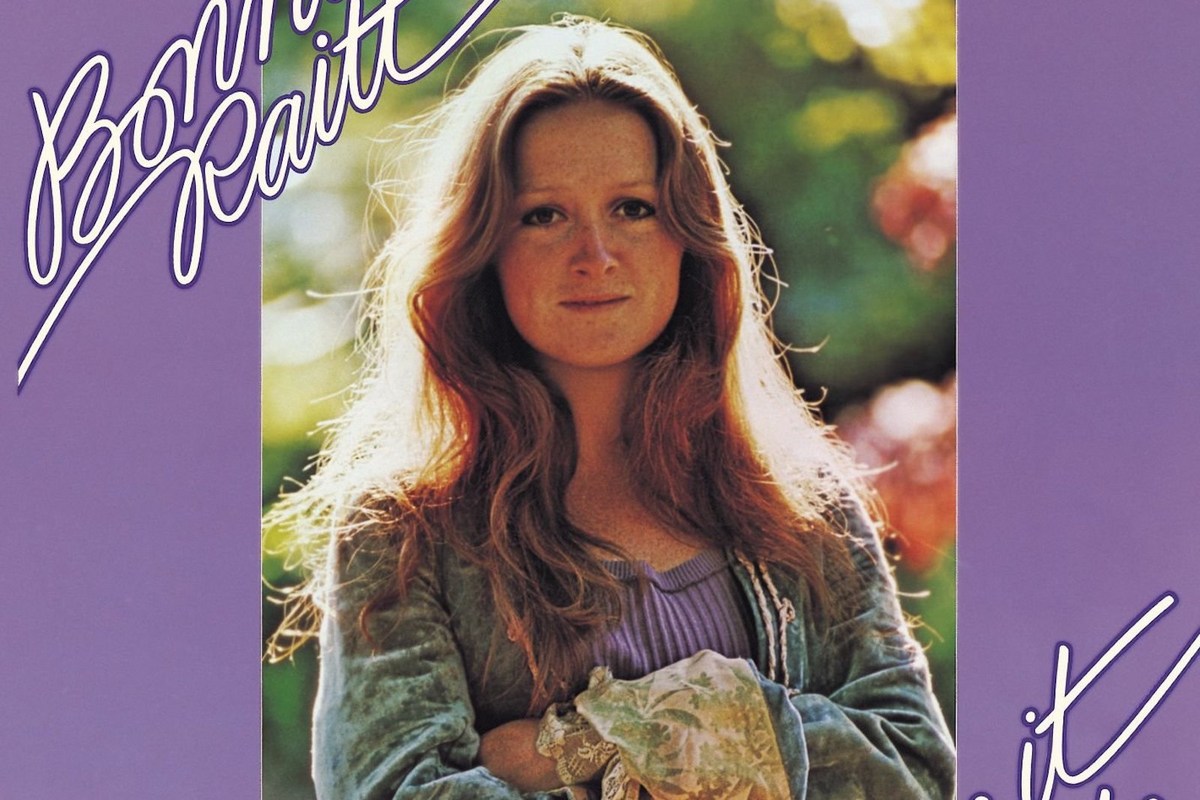

Raitt eventually accepted a record deal with Warner Bros., and she released her first self-titled album in 1971. A collection of mostly covers with a few originals, the LP sold only modestly but was generally well received by critics.

At that point, Raitt described the notion of becoming a star based on albums alone as “superfluous.” Still, when it came time to record Give It Up, she was grateful for the “complete control” Warner Bros. allowed her. “They just give me the money and I give them the tapes,” she said. “And I do respect Warners for the fact that they’d take an unknown artist like me and give me unlimited artist control.”

Listen to Bonnie Raitt Perform ‘Love Has No Pride’

This second studio effort was recorded in Woodstock, N.Y., where Albert Grossman’s Bearsville Studios was just beginning to become a retreat of sorts for musicians looking to escape the bustle of big city studios. Raitt was already accustomed to this — she recorded her debut album at an empty summer camp just outside Minneapolis — but this time, she had new musicians to work with including Paul Butterfield, T.J. Tindall and Chris Parker, among others. (Many were from around the Woodstock area.)

She also had a new producer in the up-and-coming Michael Cuscana, then mainly known for his jazz-radio programs and writing. He’d heard mention of Raitt through Waterman, but knew nothing else when he first heard Raitt perform in Philadelphia. “I didn’t even know she played guitar or sang,” he told Joe Maita in 2019. Cuscana said he was “knocked out” by her performance.

Like Bonnie Raitt, Give It Up arrived in September 1972 dotted with mostly covers. They included songs written by elder blues women Raitt admired — Barbara George’s “I Know” and Sippie Wallace/Jack Viertel’s “You Got to Know How” – as well as the then-recently released “Under the Falling Sky” by Jackson Browne. The heavy presence of covers didn’t bother Raitt.

“I’m not a songwriter,” she insisted in 1976, “and besides, that I didn’t write a song like ‘Love Has No Pride’ myself, it doesn’t mean it doesn’t feel like I wrote it myself. There is no difference whether I spread it using other people’s words or my own songs.”

Raitt recognized that a new era of interest in blues music was taking shape, but that the Black musicians who pioneered it might still get left behind. “Buddy Guy and Junior Wells, they have no faith in white kids,” Raitt told Sing Out. “They know that even if white kids happen to like blues this year, they would still rather see Johnny Winter. They know that Janis Joplin was making a certain amount of money, and that Big Mama Thornton was making maybe a fifth of it – and that’s why Junior Wells does James Brown songs.

“White people have been fickle before,” Raitt added, “and the next year blues might not be their thing: That’s why a lot of blues singers don’t work anymore, why all those clubs closed down.”

Listen to Bonnie Raitt Perform ‘You Got to Know How’

Through the ’60s and into the ’70s, countless rock ‘n’ roll bands like Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones and the Allman Brothers Band had often benefitted greatly from inspiration taken from older blues musicians and albums. Raitt wanted to bring these artists — especially if they were still living — closer to the forefront.

“It’s also true that people would rather see me or John Hammond do blues than Fred McDowell. It’s ridiculous,” she added. “Eventually, it would be real nice to put some of the older blues people on the bill with me and try to educate people. I think it’s really important.”

That’s exactly what Raitt did once Give It Up began attracting more attention. Sales were again moderate, but this became her first charting album at No. 138 and it garnered widespread critical praise. She brought along Buddy Guy and Junior Wells as her support act in 1975. Two years later, John Lee Hooker opened her shows. She also subsequently befriended Sippie Wallace.

They may have initially found it somewhat strange that a young woman raised in a Quaker family from Los Angeles could find such meaning in their music – but Raitt soon won them over. “They thought her interest in the blues was some kind of freakish quirk,” Waterman told Rolling Stone in 1975, “but she’s proud that Buddy and Muddy [Waters] and Junior and [Howlin’] Wolf now regard her as a genuine peer. Not ‘she plays good for a white person or a girl,’ but ‘she plays good.'”

In her eyes, continuing the momentum she started with Bonnie Raitt was an accomplishment. Give It Up offered a lot of what fans and critics liked about Raitt’s first album – her earthy style of singing and first-class guitar playing – but with a more polished, professional sound. “It’s a great collection of songs,” Raitt said in 1976, “it had the same funky feeling of the first album – only much better recorded, on six tracks.”

Listen to Bonnie Raitt Perform ‘Love Me Like a Man’

Especially in the early days of her career, Raitt inherently stood out amongst her male counterparts. How she fit in among her female predecessors was still a point of debate, too.

“Could Bonnie Raitt be the woman to fill the gap left by Janis Joplin’s death?” one New York Times critic asked in a 1972 review of Give It Up. “Not that Raitt sounds like Joplin, but she’s a talented singer who exudes a captivating energy.” (By the way, Raitt held a considerably different opinion about her vocals on Give It Up: “I sound like Mickey Mouse,” she said in the 1995 biography Bonnie Raitt: Just in the Nick of Time.)

Raitt grew up with two brothers, so she was used to proving herself. Still, her aim was to do so in an understated way – and female fans related to that attitude.

“I think women like me because they don’t have to be jealous,” she told Rolling Stone in 1990. “I’m one of them, you know. I’m not ridiculously beautiful, and I’m not wealthy, and I’m not intimidatingly talented. I’m probably as close to a normal person as you’ll find in the music business.”

They kept buying Give It Up, which eventually reached gold certification in 1985. Raitt was probably on stage at some intimate gig, doing what she always had. “I’d rather play in little places that only charge a dollar, be on the bill with people I really like,” she told Sing Out. “That’s the only thing that matters to me, that it’s not a rip off for the people coming in, and that I have a good time.”

Top 40 Blues Rock Albums

Inspired by giants like Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson and B.B. King, rock artists have put their own spin on the blues.