Miles Davis returned from a two-year recording hiatus with another bold new idea. True to its name, On the Corner would focus on the Black community’s street music, a blend of R&B, soul and funk that was absent any identifiable jazz aesthetic.

Gone was the cool improvisational wankery of old, replaced by the kind of dark, heavy grooves that could bring down tenement buildings. On the Corner was meant to reflect the moment, arriving on Oct. 11, 1972, as a kind of musical documentary of the sounds heard in a groaning cityscape.

But it was similarly unstructured, at least to the average U.S. record buyer. “The band settled down into a deep African thing, a deep African American groove,” Davis enthused in his autobiography, “with a lot of emphasis on drums and rhythm – and not on individual solos.”

Those solos would have been titanic. After all, Davis had assembled another all-star cast, including Herbie Hancock, John McLaughlin, Chick Corea, Jack DeJohnette, Bennie Maupin and a stellar group of Indian players, among others. But the goal was to reconnect with an urban sensibility, after years of performing before primarily white jazz fans.

Davis said “we are losing young Black people,” percussionist James Mtume later remembered. “He said I want to fuse the music that would also draw them in. See, for some reason … if you are doing something popular, it’s some kind of way more trivial. The thing is [Davis] wanted to reach that, and he wanted to bring more young Black people in – and that’s what started to happen when On the Corner came out.”

Listen to the Title Track From Miles Davis’ ‘On the Corner’

Enlisted help also included Paul Buckmaster, who’d become rock’s premier orchestral conductor after work with Elton John, the Rolling Stones and David Bowie. A Davis fan, Buckmaster encouraged a deeper dive into the avant-garde music theories of Karlheinz Stockhausen, known for both his unusual song structures and the use of electronics in classical music.

Davis adapted those ideas with an Ornette Coleman-like focus on playing in the moment, with as few preconceptions as possible. Along the way, however, he ended up tossing aside many of Buckmaster’s initial ideas, simply using his charts as starting points. Davis and his producer Teo Macero instead oversaw sessions that unfolded with relentlessly repeating beats and figures often flowing together in place of discernible melodies.

At the time, nobody knew what to do with this – not traditional jazz fans, not R&B fans, not even the guys in Davis’ band. Saxophonist Dave Liebman said he arrived to find sessions that frankly “appeared to be pretty chaotic and disorganized.”

The happenstance nature of his involvement was typical of what followed. Liebman was at a doctor’s office in Brooklyn when his mother got in touch. She said, “Someone just called named Teo Macero, and he said come now to the studio [to] record with Miles Davis,” Liebman told Nashville Scene in 2015. “I said, ‘What?’ I happened to have my soprano with me. It was complete, absolute luck of the draw. That I’m even talking to you now could be because of that moment: I had my soprano.”

Liebman proceeded to take the album’s first solo, as part of its multipart title track. He had no idea what he was doing: “That first solo is me trying to find my way to a key center because I had no headphones,” Liebman said with a laugh. All of the electric instruments were plugged directly into the recording console and were therefore inaudible. Liebman could hear only the drums. “I’m fumbling around to find out it’s actually in E flat – and that was that track.”

Everything unfolded over only three days, with principal sessions on June 1 and June 6, 1972, producing a pair of winding vamps. The frankly thunderous “Black Satin” was recorded on June 7. Macero then began cutting and splicing the tapes to create completed takes, while Davis added overdubs and various effects – often on keyboards, rather than trumpet. When he did play his traditional instrument, Davis chose to run it through a wah-wah.

Listen to Miles Davis’ ‘Black Satin’

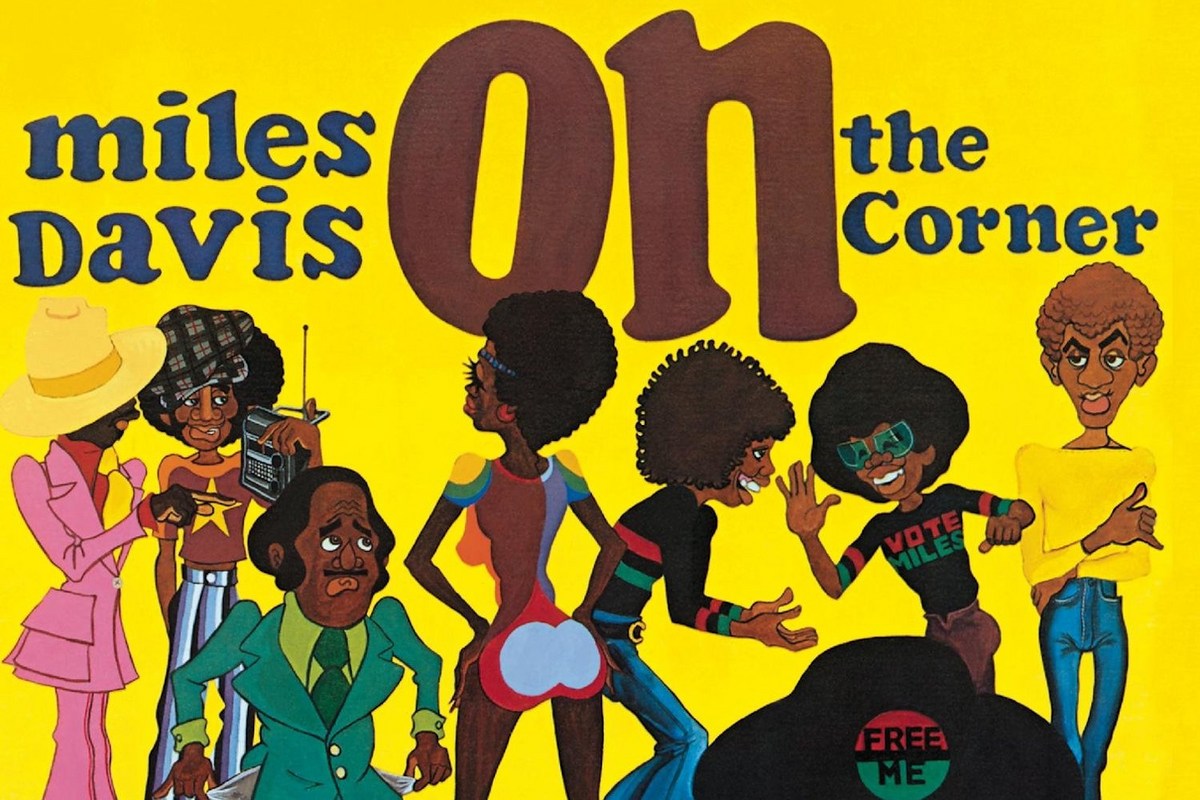

Not that you’d know going in. The On the Corner cover showcased a stylized cartoon by Corky McCoy, but Davis deliberately left off any specific player credits so that listeners would arrive with open ears. “I didn’t put those names on On the Corner specially for that reason, so now the critics have to say, ‘What’s this instrument, and what’s this?” he said in Milestones: The Music and Times of Miles Davis. “I’m not even gonna put my picture on albums anymore. Pictures are dead, man. You close your eyes and you’re there.”

Critics panned On the Corner, and listeners stayed away in droves. Davis blamed a misguided promotional approach by Columbia Records, which still framed him as a jazz artist. “Watching the way [Hancock’s funky fusion LP] Head Hunters sold just pissed me off even more,” he said in his autobiography.

Davis never created another fully formed album concept in the ’70s and briefly retired before returning with a more pop-focused sound. But something funny happened along the way: On the Corner started to feel like a revolution. The LP’s multilayered approach, defined by Macero’s mind-bending mixing and matching, creates a proto-sample free-form funk that would underpin hip-hop and electronica in the coming decades.

Once thought of as a flop, On the Corner may instead be the last great expression of Davis’ frisky mind-set, in particular in the form of “Black Satin.” The ideas whiz by like traffic from your front stoop, while much of the LP avoids the kind of approachable themes that radio programmers typically require from popular music. On the Corner was simply too forward-thinking for that.

“I said, ‘You know what? This motherfucker knew what he was doing,'” Liebman told Nashville Scene. “I realized there was a method to the madness — later on, in looking back.”

Top 25 Soul Albums of the ’70s

There’s more to the decade than Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder, but those legends are well represented.