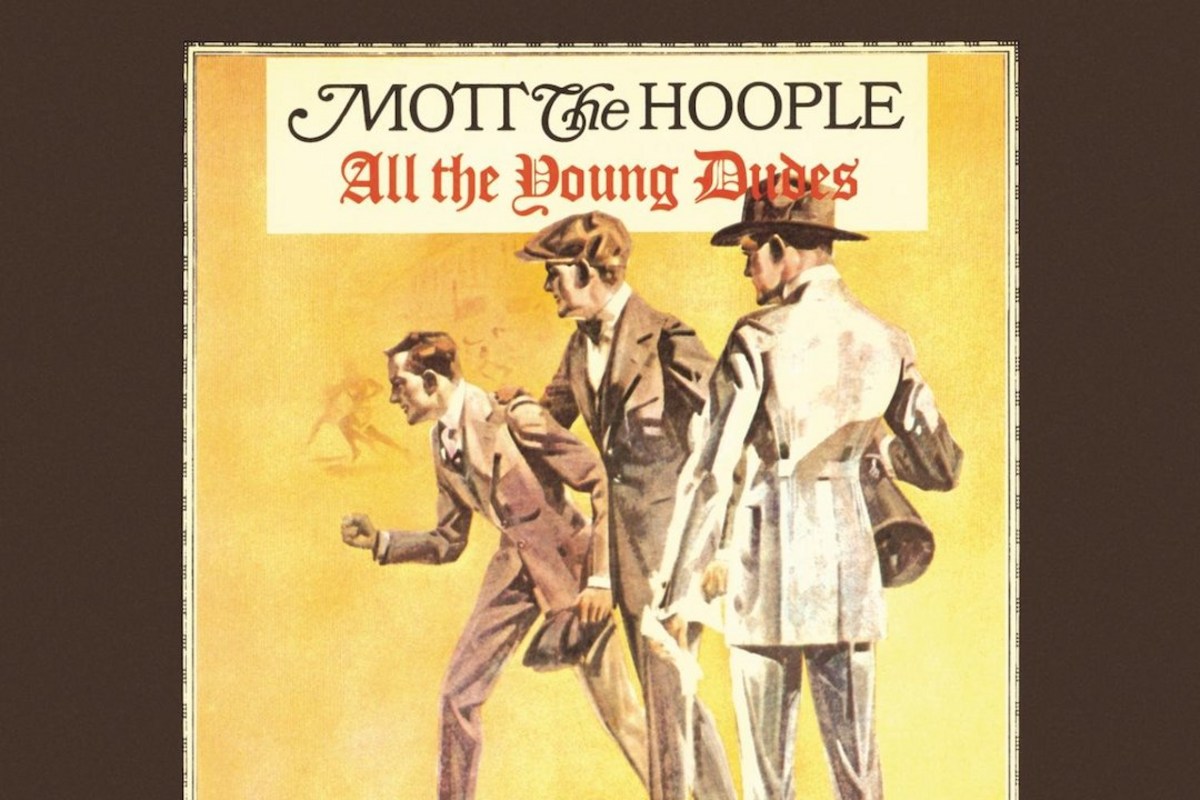

The history of rock ‘n’ roll is full of stories of dissolution and disaster, of drug-fueled tragedy and excess. Stories of pure, selfless generosity are so much rarer that they’re almost antithetical to the form. But it’s the latter that lies at the heart of one of the most purely rock ‘n’ roll subgenres, glam-rock: the story of Mott the Hoople’s 1972 album All the Young Dudes.

Hailing from Herefordshire in the West of England — a rural county whose other most famous export is its brown-and-white Hereford cattle — Mott the Hoople formed in 1969 when Island Records producer Guy Stevens heard something he liked out of a band calling itself at times the Doc Thomas Group and at other times Silence. Stevens recruited singer Ian Hunter (relegating the group’s former singer, Stan Tippins, to the position of road manager) and convinced them to change their name to Mott the Hoople, after a character in a novel he’d read while serving time for a drug offense.

Mott the Hoople released their eponymous debut album – a strutting hard-rock effort with more swagger than polish – in November 1969. It was a minor success that earned them a cult following in England, but their next three albums all failed to make much of a mark, and by the beginning of 1972, the band was on the verge of breaking up. Cue the moment of generosity. David Bowie, then at the height of his Ziggy Stardust powers, decided to save them.

Watch Mott the Hoople Perform ‘All the Young Dudes’

As Hoople keyboardist Verden Allen remembered in a 2016 interview with WalesOnline, Bowie “liked our image and sent us a telegram inviting us to his agent’s office in London.” There, he played a song he had written for them. As Bowie told NME, “I literally wrote that within an hour or so of reading an article in one of the music rags that their breakup was imminent. I thought they were a fair little band, and I thought, ‘This will be an interesting thing to do, let’s see if I can write this song and keep them together.'”

The song Bowie wrote and played for the band in his agent’s office — on a blue guitar while wearing a blue catsuit — was “All the Young Dudes.” It would become one of the definitive anthems of the glam-rock movement while giving Mott the Hoople a bona-fide hit and making their career. And for good measure, Bowie offered to produce the band’s next album, which would also be called All the Young Dudes.

The album has Bowie’s fingerprints all over it. Opening with an understated version of the Lou Reed classic “Sweet Jane,” it immediately finds its groove in a kind of glossy showmanship that fits the band’s strengths perfectly. Hunter’s songwriting shines on tracks like the midtempo, blues-riff-driven “Momma’s Little Jewel” and the anthemic “One of the Boys.” Guitarist Mick Ralphs’ cool, in-the-pocket style is reminiscent of Keith Richards, and he displays some writing chops in “Ready for Love/After Lights,” the first half of which he would resurrect with the subsequent group Bad Company.

Bassist Pete Watts and drummer Dale “Buffin” Griffin swing capably between driving hard-rock rhythms and the cheekier grooves that make up much of the album’s glam fare, such as “Sucker.” And Bowie’s steady hand as a producer gives the album a strong, clean sound, lending a perfect amount of cosmic sheen to the band’s power riffing. Several tracks — such as the gorgeous ballad “Sea Diver” that closes the album — wouldn’t be out of place on Bowie’s 1972 masterpiece, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars.

Listen to Mott the Hoople’s ‘Sucker’

But the heart of the album is “All the Young Dudes.” From the iconic opening guitar line and Hunter’s languid, Bob Dylan-esque talk-singing to the operatic chorus and soaring arrangement, the song helped define glam as one of the most flamboyant, sexually supercharged, gender-bending and rebellious moments in rock history.

The song’s lyrics celebrate alternative sexuality — the “I’m a dude, dad!” refrain reads like a cross between “Guess what: I’m gay!” and “I’m going to dress like a girl if I want, so get over it!” — and detail the difficulties endured by people who embrace that sexuality. Billy, one of the song’s young dudes, is already talking about committing suicide even though he’s not yet 25. Lucy “dresses like a queen” but is sometimes forced to “kick like a mule.” The song’s narrator is distressed because they couldn’t ever quite get down with the more straightforward “revolution stuff” offered by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

That all of this subversion was delivered by a band whose members were not gay wasn’t confusing or accidental but part of the point of glam rock. It was about strutting whatever sexuality you wanted to strut at the moment, about dressing up and being who you wanted to be, about celebrating people who had up until that point been driven into hiding by the mainstream. It was an inclusive, joyous moment in music, founded in part on an act of unadulterated generosity.

Top 100 ’70s Rock Albums

From AC/DC to ZZ Top, from ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ to ‘London Calling,’ they’re all here.