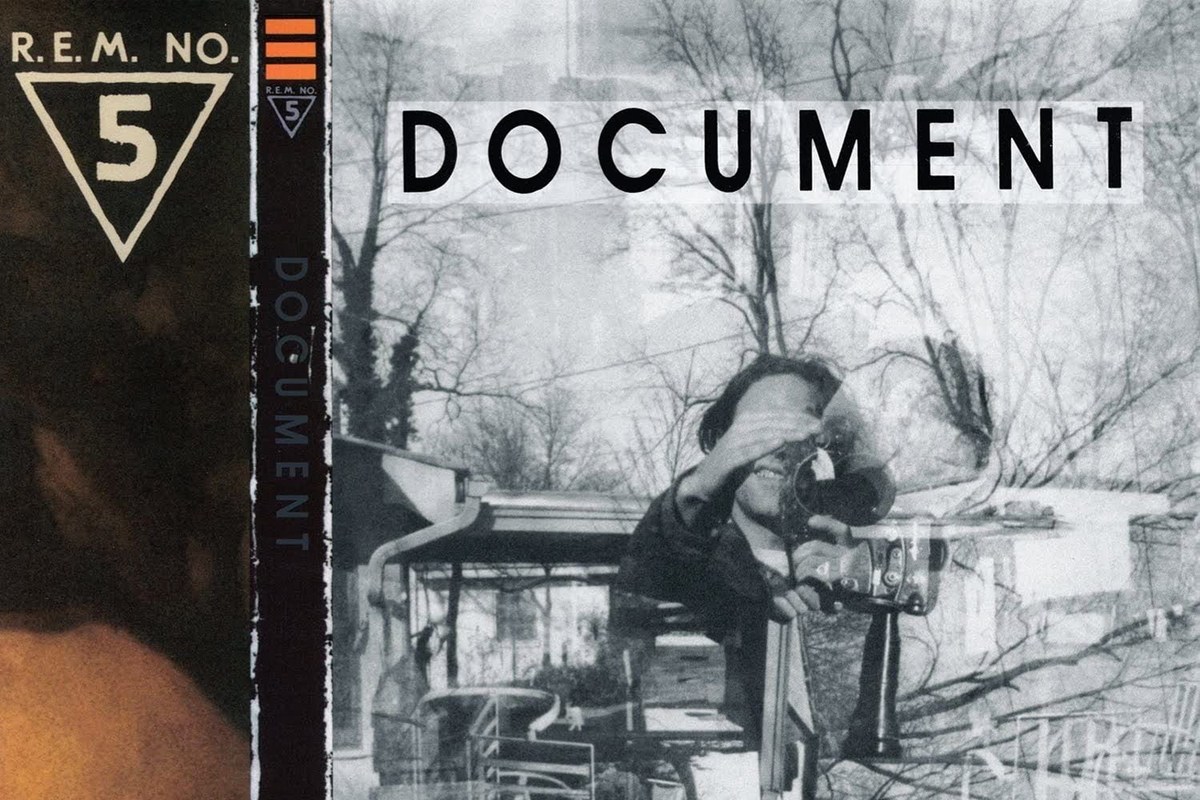

It’s the first week of December 1987, and R.E.M. has just finished a tour of Europe and North America, playing to the largest crowds of the group’s career so far. They are on the cover of Rolling Stone, underscored with the declaration “America’s Best Rock ‘n’ Roll Band.” Their latest album, Document, is fast approaching platinum sales in the U.S. And they have a Top 10 hit.

Most bands would be thrilled, ready to forge ahead with declarations of continued greatness (remember what Bono was saying about U2 in 1987). But the guys in R.E.M., bandmates for seven years, were more surprised by their quantum leap in popularity, maybe even shocked by it, and skeptical.

“I can’t believe that we’re up there with [Bruce] Springsteen or whatever,” singer Michael Stipe said in that Rolling Stone cover story. “It doesn’t really mean that much, but it does to the industry, and I guess to kids that read. And my mom got kinda weepy … No, she didn’t. But she couldn’t believe it, either.”

The disbelief made sense. R.E.M. had been promised a fabled “breakthrough” by music industry experts every time they’d put out a new LP, going back to 1983’s Murmur. That had yet to be seen and the band had long given up any such desire. Sure, the critics were adoring (only to be outdone by the band’s hardcore fans) and sales improved with every release – but this was a steady sort of growth, in line with R.E.M.’s underground status.

“There are a few things on this album that could do well on Top 40 radio,” guitarist Peter Buck told Rolling Stone, just before Document’s release on Aug. 31, 1987, “but then again I can’t imagine it happening, knowing us. So I don’t know if I have any commercial expectations for this one at all. I assume it will sell some, somebody’s got to buy it. I know my mom will buy three or four. I don’t see this as the record that’s going to blast apart the chart. Although you never know. Weirder things have happened.”

If R.E.M. happened to scrape the singles charts, that was fine, as long as they could tour and make records, each one with a sonic approach different from the one that came before. Document, the band’s fifth album, fits firmly in that tradition. As with previous LPs, the quartet looked to build on what they had done, while simultaneously moving in an alternate direction.

Lifes Rich Pageant in 1986 had brought a cleaner and richer sound to the band’s recordings, partially by way of producer Don Gehman. In the realm of R.E.M., it was more direct musically and lyrically, with Buck’s spindly guitar wrapped around Stipe’s often environmentally conscious pleading. Stipe and Buck, along with bassist Mike Mills and drummer Bill Berry, wanted this next record to be a bit weirder.

Listen to R.E.M.’s ‘Fireplace’

“This time around we wanted to make a tougher-edged record,” Buck said. “This time we wanted to make a loose, weird, semi-live-in-the-studio album. We wanted to have a little tougher stance.”

With that notion, the band brought on producer Scott Litt. At that point, Litt had gained the most attention for helming Katrina and the Waves’ “Walking on Sunshine,” but R.E.M. was curious because he also had produced the dB’s Repercussion. After recording the one-off “Romance” with Litt for the Made in Heaven soundtrack, the guys thought it would be interesting to make a full album with him.

R.E.M. and Litt agreed to record the album in the spring of 1987 at Nashville’s Sound Emporium studio – chosen by Buck, “because it [looked] a little like a Polynesian bar,” according to Stipe. Litt’s mission aligned with R.E.M.’s in wanting to change the band’s sound. He hadn’t been a huge fan of the group before that time because he felt their records had been too “murky” sounding.

“I’ve always liked full-range records and treating vocals with care,” Litt told the Chicago Tribune in 1994. “With R.E.M., I thought it was important to show that the music belongs on the radio, that it was every bit as worthy as Whitney Houston or whatever else was on there.”

While writing and recording Document, the members of R.E.M. were less concerned with the radio than creating a record that reflected the modern world circa 1987. That’s why the LP’s title was eventually selected, instead of alternate choices “No. 5” and “Table of Content” (both of which appear on the sleeve), as well as “Last Train to Disneyland” (which does not).

Listen to R.E.M.’s ‘Exhuming McCarthy’

Stipe, as the band’s singer and primary lyricist, crafted political and observational songs that were as pointed as the blend of rock, funk and folk music that was coming from Berry, Buck and Mills. “Exhuming McCarthy” drew connections between the Red Scare and Iran-Contra. “Welcome to the Occupation” decried U.S. meddling in Central America. Even the album’s lone cover, of Wire’s “Strange,” seemed to reflect how R.E.M. felt about current events. Meanwhile, “Finest Worksong” opened the album with a call-to-arms – “The time to rise has been engaged” – forecasting how these 11 tracks would be doused in righteous anger.

“Michael is really concerned – we all are – about this neo-conservative wave in America,” Mills told the Globe and Mail in August 1987. “With all the repression of personal freedoms, the knee-jerk reactionism, it’s the sort of atmosphere old Joe [McCarthy] would fit well into, hence the song. But we try not to be dire about it. There’s a lot of whimsical humor and irony in Michael’s writing that we don’t really get credit for. I think people miss that a lot of the stuff we do is partly tongue-in-cheek.”

That goes for one of Document’s (and R.E.M.’s) most famous tracks, “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (and I Feel Fine),” which merged real-life fears – like Stipe’s earthquake terror – with political references and daydreams about famous people with the initials L.B. having a birthday party with cheesecake and jelly beans. The song also forecasted the future’s media-saturated information overload with its rapid-fire lyrics, which exit the singer’s mouth like slugs from a Howitzer.

“End of the World” would become a modest hit on its way to pop culture immortality, whereas “The One I Love” would resonate much more immediately. With Berry’s crisp drum riff launching into Buck’s barbed wire guitar, the album’s lead single arrested listeners’ attention. The track was the one that beat the odds, buzzing radio stations internationally and earning R.E.M. their first Top 10 hit in America by rising to No. 9. Stipe got a kick out of casual fans who didn’t listen closely enough to hear him declare that the titular object of this dedication was also just “a simple prop to occupy my time.” “It’s a brutal kind of song, and I don’t know if a lot of people pick up on that,” he told Rolling Stone. “But I’ve always left myself pretty open to interpretation. It’s probably better that they just think it’s a love song at this point … I don’t know. That song just came up from somewhere, and I recognized it as being real violent and awful.”

Watch R.E.M.’s ‘The One I Love’ Video

Whether because of “The One I Love”‘s darker tendencies or despite them, the single brought R.E.M. hordes of new fans who pushed Document into the Top 10 and made it the band’s first-ever platinum release by January 1988. In the meantime, the band had completed their Work Tour to promote the album, which saw members struggling with the group’s increasing fame. Buck had a freak-out after playing to 12,000 fans and witnessing the bruising physicality of a general admission crowd. Stipe found himself becoming increasingly hostile to certain members of the audience.

“There was a point in the ’80s when I looked out at my audience and I saw people that – were I not on stage – they’d sooner slug me as they walked by me on the sidewalk,” Stipe told Filter Magazine in 2003. “These were other people. I was an ugly, horrible person onstage then [Laughs] – spewing about Reagan and about this and that. It’s where a song like ‘Exhuming McCarthy’ came from. There was a point where I looked out and I saw these people and I realized: I’m the performing monkey. I’m the dancing clown … And it was really offensive to me and so I reacted the way anyone would react in that situation: you get very defensive and very insecure and very angry and you want to shove down people’s throats who you really are and see how much of it they can take. OK, well, I thankfully kind of grew out of that, but I had to learn the hard way.”

In so many ways, Document was a massive turning point for R.E.M., filled with big hits and hard lessons. As the band’s final studio LP with I.R.S. Records, it marked the ending of the band’s underground years – as R.E.M. would jump to Warner Bros. the following year and become an act that could fill arenas. But it was also the beginning of a new era, a fruitful studio partnership with Scott Litt resulting in a bevy of blockbuster albums and many more radio songs.

“We never made giant steps to make ourselves a viable, hit-making American band for American radio,” Stipe reflected on In the Studio With Redbeard. “Radio came to us … pop culture just swung into our little, stubborn trajectory.”

Watch R.E.M.’s ‘It’s the End of the World as We Know It (and I Feel Fine)’ Video

Top 100 ’80s Rock Albums

UCR takes a chronological look at the 100 best rock albums of the ’80s.