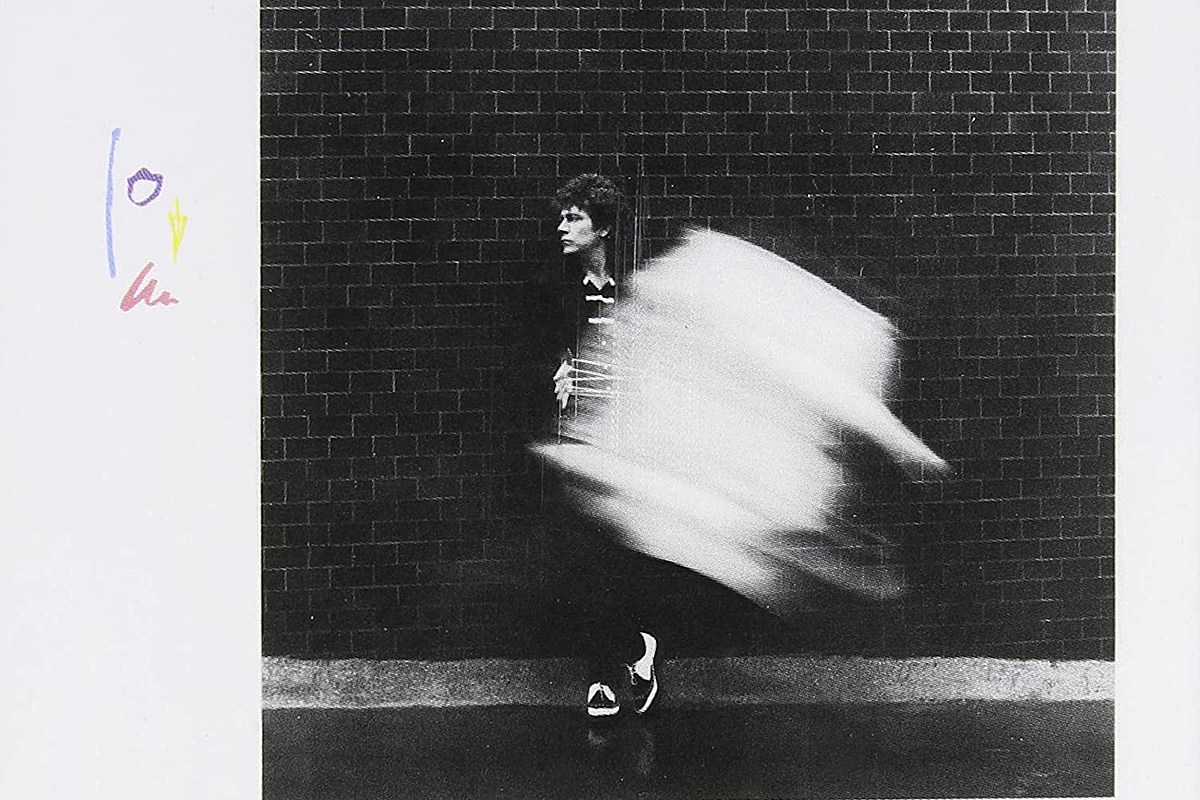

Robert Plant didn’t change the formula much for his sophomore solo album, at least on the surface.

The Principle of Moments, released on July 11, 1983, found him once again writing and/or performing with a core group featuring Robbie Blunt, Jezz Woodroffe and Phil Collins – just as he had on 1982’s Pictures at Eleven. He also continued to distance himself from his legacy in Led Zeppelin, both in the studio and (after the release of this studio effort) out on the road.

Yet something was different about The Principle of Moments, and it had everything to do with the songs.

His debut could sometimes – despite its Top 5 finish in both America and the U.K. – feel no more than serviceable. Not so the gumption-filled follow up, which featured Plant’s first two solo Top 40 Billboard hits in “Big Log” and “In the Mood,” and a rock-radio staple in “Other Arms.”

None of it sounded all that conventional, at least within the emerging synth-pop landscape of MTV. But it also couldn’t have been further away from the stadium-rattling hard rock excursions associated with his time playing with Jimmy Page in Led Zeppelin. That was the point, Robert Plant argued.

“I was just trying to do stuff that was as far removed from Zeppelin as possible,” Plant told the Los Angeles Times in 1988. “It wasn’t commercial, but I wanted to be commercial – on my terms. I was on some kind of mission to make mildly obscure music but at the same time be a success on the pop platform.”

This flinty search for something new would be the hallmark of Plant’s intriguing solo career.

Watch Robert Plant’s ‘Big Log’ Video

Deeper album cuts here like “Messin’ with the Mekon” and “Wreckless Love,” with their respective musical references to “Black Dog” and “Kashmir,” were the only overt nods to what came before. More notable was the nuanced vocal performance on the No. 11 UK smash “Big Log,” which found Plant singing with a suave new assuredness alongside Blunt’s guitar atmospherics. Plant is similarly restrained on key tracks like “In the Mood” and “Thru’ with the Two-Step,” the latter of which showcases Woodroffe’s gorgeous keyboards.

Collins, then on the cusp of his own solo superstardom, offers a similarly light touch at the drums. He appeared on all but two of the album’s eight tracks, where he was spelled by Barriemore Barlow of Jethro Tull fame. This new relationship then helped bridge the gap between Plant’s two musical eras as Collins sat in for a subsequent Led Zeppelin reunion at Live Aid.

“A drummer contacted me and said, ‘I love [late Zeppelin drummer John] Bonham so much I want to sit behind you when you sing.’ It was Phil Collins,” Plant once told the Pulse of Radio. “His career was just kicking in and he was the most spirited and positive and really encouraging force, because you can’t imagine what it was like – me trying to carve my own way after all that.”

Hit singles in hand, Plant finally had a platform for every intriguing experiment, reunion and side road that would follow. That included returns to his deepest roots (1984’s The Honeydrippers: Volume One and 2002’s Dreamland), as well as spirited collaborations with Page (1988’s Now and Zen and 1998’s Walking into Clarksdale).

He also traveled to places perhaps undreamt of my his staunchest early fans (2005’s Mighty ReArranger and 2014’s Lullaby and the Ceaseless Roar). The seeds were sown on Principle of Moments.

Led Zeppelin Solo Albums Ranked

There have been vanity projects, weird detours and huge disappointments – but also some of the best LPs of the succeeding eras.

Why Led Zeppelin Won’t Reunite Again