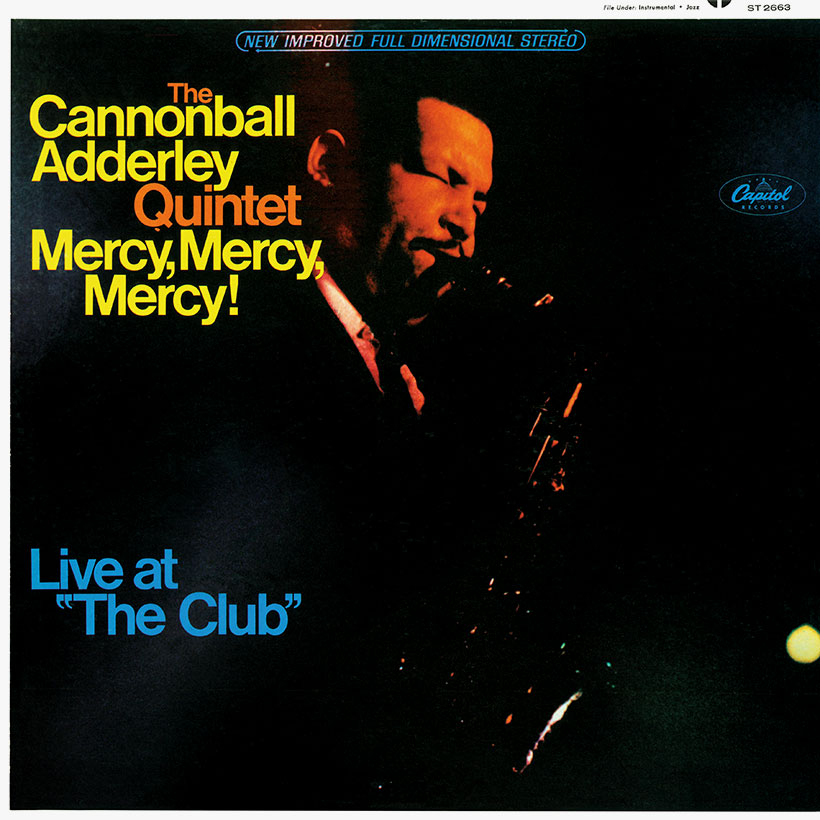

When 27-year-old Julian “Cannonball” Adderley went up to New York from his native Florida in the summer of 1955, he blew the Big Apple jazz community away with his thrilling alto saxophone playing. A hugely impressed Miles Davis was among his champions, and big things were expected of the saxophonist. The recent death of another altoist, bebop legend Charlie Parker, who had died earlier that same year, at the tragically young age of 34, left a gaping void in the jazz world, and many saw Cannonball as the man to fill it. It was a heavy responsibility and, at first, the portly ex-teacher from Tampa struggled under the burden of expectation; his early LPs for Emarcy and Mercury failed to live up to the promise of his talent. But Miles Davis came to Cannonball’s rescue, making a rare sideman appearance on the saxophonist’s Blue Note LP, Somethin’ Else, in 1958, and then recruited him when he expanded his quintet to a sextet, which recorded the classic 1959 LP Kind Of Blue. These albums paved the way for further high points in Adderley’s career, among them Mercy, Mercy, Mercy! Live At “The Club”.

Listen to Cannonball Adderley’s Mercy, Mercy, Mercy! Live At “The Club” at Apple Music and Spotify.

Mercy, Mercy, Mercy! is a live album that captures Cannonball seven years on from the triumph of Kind Of Blue, by which time he was 38 years old and a noted bandleader in his own right. Importantly, he had also found his niche as a purveyor of a popular style called soul jazz, a more accessible variant of bebop that dug deep into gospel and blues styles.

One of Cannonball’s key musicians during this timeframe was his pianist, Austrian-born Joe Zawinul, who had been with him for four years at that point and would go on to find fame in the 70s as the co-founder of the fusion giants Weather Report. As well as being a fluent pianist well versed in the bebop argot, Zawinul was also a gifted composer and his compositions were beginning to shape the stylistic trajectory of Adderley’s band. Also crucial to Adderley’s sound was the presence of his younger brother, Nat, who played the cornet. Playing behind the Adderley brothers on this particular album was a sturdy but pliable rhythm section comprising bassist Vic Gatsky and drummer Ron McCurdy.

Though the sleevenotes for Mercy, Mercy, Mercy! state that the album (produced by David Axelrod) was recorded live in July 1966, at a venue called The Club, a newly-opened Chicago nightspot owned by a local DJ, E Rodney Jones, it was, in fact, recorded over 2,000 miles away in Los Angeles, in October of that year.

The tracks that made up Mercy, Mercy, Mercy! were cut in Hollywood at Capitol Studios, in front of an assembled congregation of family members, fans and music-biz people, to help give it a live concert feel. Cannonball had, in fact, recorded live at The Club in March ’66, and though that performance had been slated for release, it didn’t come out at the time (it eventually surfaced in 2005, 30 years after the saxophonist’s death, as the album Money In The Pocket). It’s feasible that Cannonball wanted Mercy, Mercy, Mercy! to give the impression of having been recorded in Chicago, in order to avoid disappointing The Club’s owner, who was a friend.

Comprised of six varied tracks, Mercy, Mercy, Mercy! is an album that showcases the exciting onstage alchemy of Cannonball’s band, who veer from intense, cutting-edge modal jazz (“Fun”), to rousing pop-soul beat ballads (“Mercy, Mercy, Mercy”), and danceable, finger-snapping soul jazz in the shape of “Sack O’ Woe,” one of Adderley’s signature tunes, where Joe Zawinul’s driving piano takes the listener straight to church.

But it’s “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy” – which elicits enthusiastic shouts, hollers, and spontaneous clapping from the audience – that is the album’s keystone. Defined by an infectious chorus and infused with a strong, gospel feeling, the song is now regarded as a quintessential example of soul jazz. Its author was Joe Zawinul, who also contributed the cool groove “Hippodelphia” to the album.

As soon as he’d written “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy,” Zawinul knew his song had the potential to be a hit, but felt it needed an electric keyboard to make it funkier and get its message across, as he told this writer in 2006: “I used to play ‘Mercy, Mercy, Mercy’ on the acoustic piano. It came off pretty good but I told Cannonball, ‘Listen, man, I played on Wurlitzer pianos during my tours in the 50s in American clubs and air bases. Let’s find a studio that’s got one.’ I found one in 1966 at Capitol Records in Hollywood. I said, ‘I will play the melody on the Wurlitzer instead of the acoustic piano. We’re gonna have a smash.’ And so it was. It was the first recording with the Wurlitzer I did in America.”

Released as a single in January 1967, “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy” rose to No.2 in the US R&B charts and No.11 in the pop lists, while its parent album topped the US R&B albums chart and made No.13 on the Billboard 200. There were cover versions of the song, too, most notably by Marlena Shaw, who scored a Top 40 R&B hit with a vocal version in 1967.

In the wider scheme of things, the song showed that electric keyboards had a role in jazz – indeed, a year later, in 1968, Miles Davis starting using electric pianos in his bands and employed Joe Zawinul as a sideman. Zawinul would help the Dark Magus map out the musical terrain of his jazz-rock-fusion albums In A Silent Way and Bitches Brew.

For Cannonball Adderley, though, “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy” – both the album and the single – would mark the commercial pinnacle of his career, transforming a man once deemed “the new Charlie Parker” into the unlikeliest of 60s pop stars.

Mercy, Mercy Mercy! Live At “The Club” can be bought here.