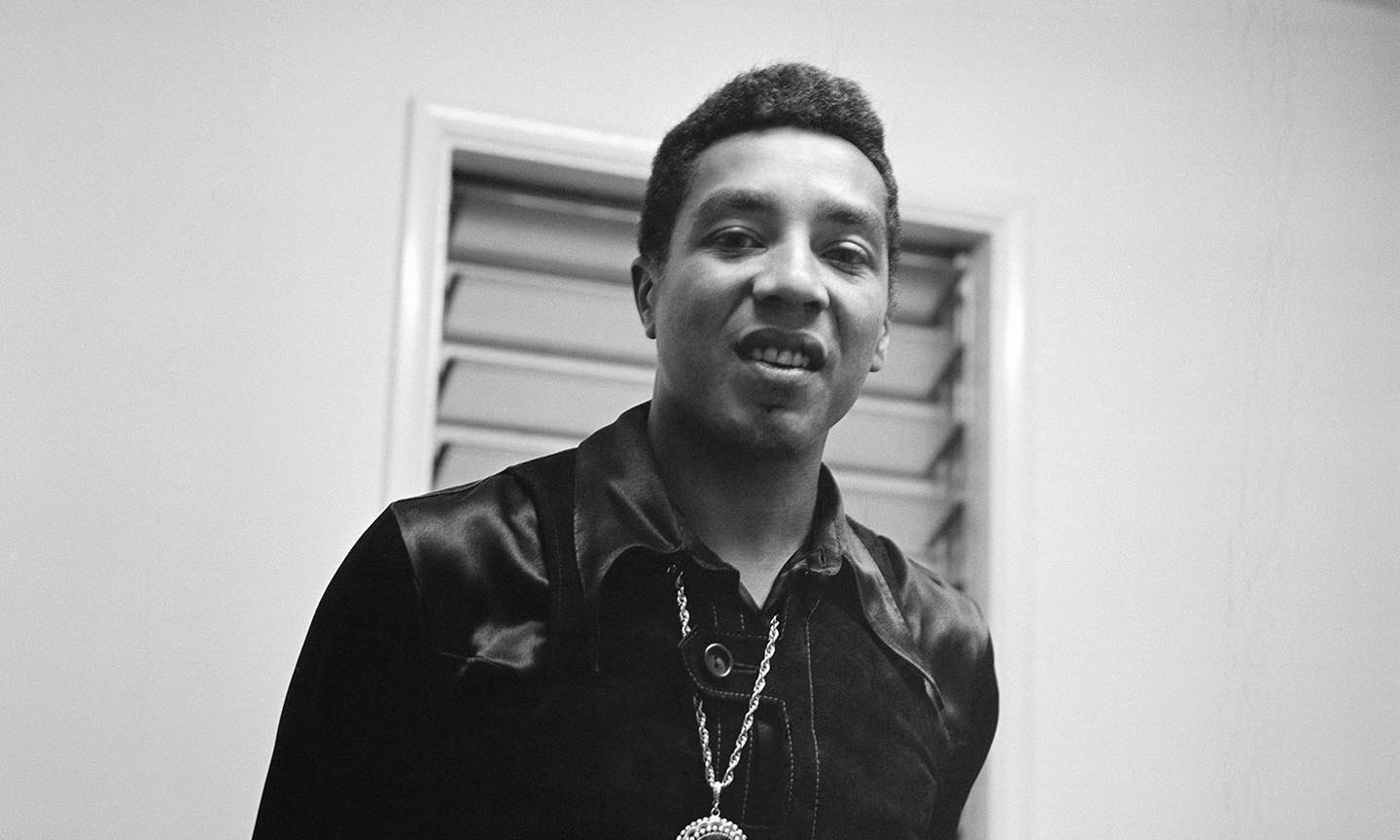

Don’t worry, we’re not going to repeat the Bob Dylan quote about Smokey Robinson. We know you are sick of it being trotted out at every opportunity, and if you don’t know it, it’s not hard to find. Smokey doesn’t need another songwriter to confirm his greatness. His work speaks for itself: he’s got the write stuff. Our job here is to chart a course through some of the musical miracles he created for Motown, whether written to perform himself or with The Miracles, or for other artists blessed by the gift of his songs.

Smokey Robinson was a pioneer. Many statements have been made to the effect that Motown’s artists began to wrest control of their careers at the start of the 70s by writing their own material, but Smokey began doing it in the late 50s. Every word, every melody he dreams up has soul, and there’s a Smokey song for everyone. What follows will give you a taste of his greatness.

Listen to the best of Smokey Robinson on the Motown Songbook playlist on Apple Music and Spotify.

Miracle of creation

It’s said that Smokey Robinson wrote 100 songs before Berry Gordy, Motown’s boss, declared one to be worth recording. Chances are it was more than that, as Smokey, who was born on February 19, 1940, composed a song for a school play when he was seven, and from an early age he bought Hit Parader, a magazine which printed the lyrics of chart songs, to study them closely and decipher how they worked. In this instance, practice made perfect. On the advice of Gordy, who had written several hits for R&B star Jackie Wilson, Smokey began to think more about the structure in his songs and to give their stories continuity. By 1960, after a couple of well-received singles with The Miracles, Smokey’s first major writing success arrived with “Shop Around,” which took parental love advice to No.2 in the US pop charts.

Clearly, Smokey didn’t heed what mama said, because by the time of “You’ve Really Got A Hold On Me,” a Top 10 smash in ’62, he was hooked on one girl. Not only was it a brilliant performance by The Miracles, it proved that Smokey’s songs had legs. The following year, “You’ve Really Got A Hold On Me” was covered by a rapidly rising Liverpool group for their second album, With The Beatles, guaranteeing a rush of royalties for Smokey and Motown’s publishing company, Jobete. From this point on, songs bearing the Robinson writing credit would be scoured for hit potential by other artists. The Beatles did a great job on the tune, but if you want to hear the definitive version, it’s got to be The Miracles’ emotive cut. (Without a hint of irony, The Supremes’ 1964 tribute album to the Fabs and the Mersey sound, A Bit Of Liverpool, contained a version of “You’ve Really Got A Hold On Me.” Um, cart before the horse?)

My go-to guy

As was the way at Motown, Smokey Robinson found himself in great demand among the company’s other singers, all seeking a sprinkle of his songwriting stardust. Smokey returned to hard-headed love advice when writing “First I Look At The Purse” for The Contours (1965). He was more romantic on “My Guy,” a smash hit for Mary Wells (1964) and a song he answered himself with “My Girl” (1965), a mega-hit for both The Temptations and Otis Redding, and generously provided the Tempts with “The Way You Do The Things You Do,” “It’s Growing,” “Get Ready” and an entire album’s worth of gems on The Temptations Sing Smokey.

Equally fluent at writing for women and men, Smokey penned “Operator” for Brenda Holloway (1965), and blessed the magnificent Marvelettes, who ranked among Motown’s most soulful groups, with the stark warning “Don’t Mess With Bill” (1965) and the rather more philosophical “The Hunter Gets Captured By The Game” (1966) (Bill, incidentally, was another nickname for William “Smokey” Robinson.) Marvin Gaye, who was not short of writing chops himself, was nonetheless delighted to receive “Ain’t That Peculiar” (1965), which many fans regard as his greatest mid-60s single. “One More Heartache” and “I’ll Be Doggone” are also candidates for that accolade – and Smokey wrote those too.

What love has joined together…

Not content with feeding hits to other artists, Smokey Robinson had his own group to write and perform with. Often considered masters of the ballad, thanks to the likes of the majestic “Ooo Baby Baby” (1965) and the heartbreaking “Tracks Of My Tears” (1965), The Miracles could also kick up a rumpus on tunes such as “Going To A Go-Go” (1965) and “The Tears Of A Clown” (1970). These songs are well remembered today, but Smokey and The Miracles’ brilliance still oozed from album tracks and B-sides. Songs which are heard far less today have remarkable depths. “Save Me,” the B-side of “Going To A Go-Go,” opens like a twee ditty, with tidy piano and ticking bongo drums. But that polite arrangement only serves to hide Smokey’s tale of total personal disaster: his lover has gone and he’s at the end of his tether – a man drowning in a sea of emotion now that his romance is on the rocks.

The song resurfaced in Jamaica with all its darkness exposed as “Rude Boy Prayer” by Alton Ellis, Zoot Sims and Bob Marley’s Wailers, the pain of lost love adapted to the terror of falling into a pit of crime. “Choosey Beggar,” a 1965 B-side, also deserved to be heard more, with Smokey turning down potential true loves in favour of one girl in particular – but he has to grovel to get her. The Miracles’ Going To A Go-Go album (1965) in particular is packed with Smokey’s mid-60s songwriting goodness.

Got a job

Smokey suffered from a certain amount of conflict in his roles at Motown. He was an executive of the company. He wrote and produced for other artists. The Miracles were often on the road. He had to write and produce for them. It was a lot of responsibility. Towards the end of the 60s, he had identified touring as an aspect of his role he could do without, and decided to leave Smokey Robinson And The Miracles in the hope of making his working life more manageable. However, in 1970 the group landed a No.1 with “The Tears Of A Clown,” just as Smokey was about to “hand in his notice,” so he stayed with them for another couple of years, delivering a further big US hit in ’71 with the subtle and mature “I Don’t Blame You At All.” A notable song for another act recorded at the starts of the 70s was Four Tops’ “Still Water.” which was a precursor to the sound of Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On. But Smokey also wrote for the biggest Motown group of all, which helped him…

Reign supreme

Smokey’s songs had been recorded by The Supremes several times down the years, as Motown liked to recycle its hit material. Diana Ross And The Supremes hit with Smokey’s faintly autobiographical “The Composer” in 1969, but after Ms Ross quit for a solo career, Smokey took charge of their fourth album without their former lead voice, and many fans regard Floy Joy (1972) as The Supremes’ 70s album most in touch with the true Motown sound. Smokey’s production was both classically Detroit-sounding and yet expressively funky, as befitting its era. Smokey wrote or co-wrote all nine tracks, which include the magnificent stomping title song, the deeply groovy, minor-key melody of “Automatically Sunshine,” and the epic, almost dub-styled “Now The Bitter, Now The Sweet.” It was a beautiful album, but a one-off. Smokey quit The Miracles in 1972 and soon had other fish to fry.

The one you need

Smokey’s solo career started reasonably strongly, with the 1973 album Smokey delivering a hit single in “Baby Come Close,” but the most notable fact about the follow-up LP, Pure Smokey, appeared to be that it triggered ex-Beatle George Harrison to write a tribute song of the same name dedicated to the Motown legend. Critics and DJs wondered if Smokey could really make it alone. Smokey’s third solo album answered that. 1975’s A Quiet Storm not only found a niche that the solo, all-grown-up Smokey fitted, it created a whole new format of soul music that took its name from the album’s title track: a humming, pulsing wash of adult-oriented, tenderly expressed emotion. “Baby That’s Backatcha” was also a big hit with its mellow yet funky tale of tit-for-tat relationships. Smokey’s brilliance as a writer had not dissipated, and “Cruisin’” (1979) was another example of his quiet storm-styled songwriting at its best.

Seconding that emotion…

Smokey did not usually write alone. Among his closest collaborators was Marv Tarplin, The Miracles’ guitarist, who broke a rare writing block for Smokey when the two wrote “Cruisin’” together. Additionally, various members of The Miracles contributed to many of the group’s hits, such as Pete Moore, Bobby Rogers and Ronald White. Motown house songwriter Al Cleveland co-created many late-60s wonders with Smokey, including the much-loved “I Second That Emotion.” “The Tears Of A Clown” was co-authored by another Motown giant, Stevie Wonder, with Wonder’s regular co-conspirator, Hank Cosby. And Motown boss Berry Gordy shaped and rewrote some of The Miracles’ earliest successes, including “Shop Around.” Genius works with genius.

Smokey Robinson’s songs continue to resonate. It doesn’t take a search helicopter with a spotlight to track down a cover of “Get Ready,” “Ooo Baby Baby” or “My Girl,” for example. While other songwriters have hailed his sweet and tender vocal talent, without his unique gift for songwriting, Smokey might have been just another great Motown singer. With pen in hand, however, he has become a legend. And he still works on new songs every day. Write on, write on…

Listen to the best of Motown on Apple Music and Spotify for more classics penned and sung by Smokey Robinson.