Stevie Wonder’s early 1972 release Music of My Mind was an incremental achievement, as he neatly refined the approach of earlier, more uneven albums. The follow-up Talking Book arrived on Oct. 27, 1972, as something else entirely: a crystallization of Wonder’s self-contained genius.

He plays all of the instruments on “You and I (We Can Conquer the World),” “Big Brother,” “Blame It on the Sun” and “I Believe (When I Fall in Love It Will Be Forever).” He handles everything but the horns on “Tuesday Heartbreak” and “Superstition.” Elsewhere, Wonder is paired with only guitars on “Maybe Your Baby” and “Lookin’ for Another Pure Love,” and with congas on “You’ve Got It Bad Girl.”

He produced Talking Book, was the sole credited songwriter on six of its 10 songs (including two chart-topping singles) and co-wrote the rest with Syreeta Wright and Yvonne Wright.

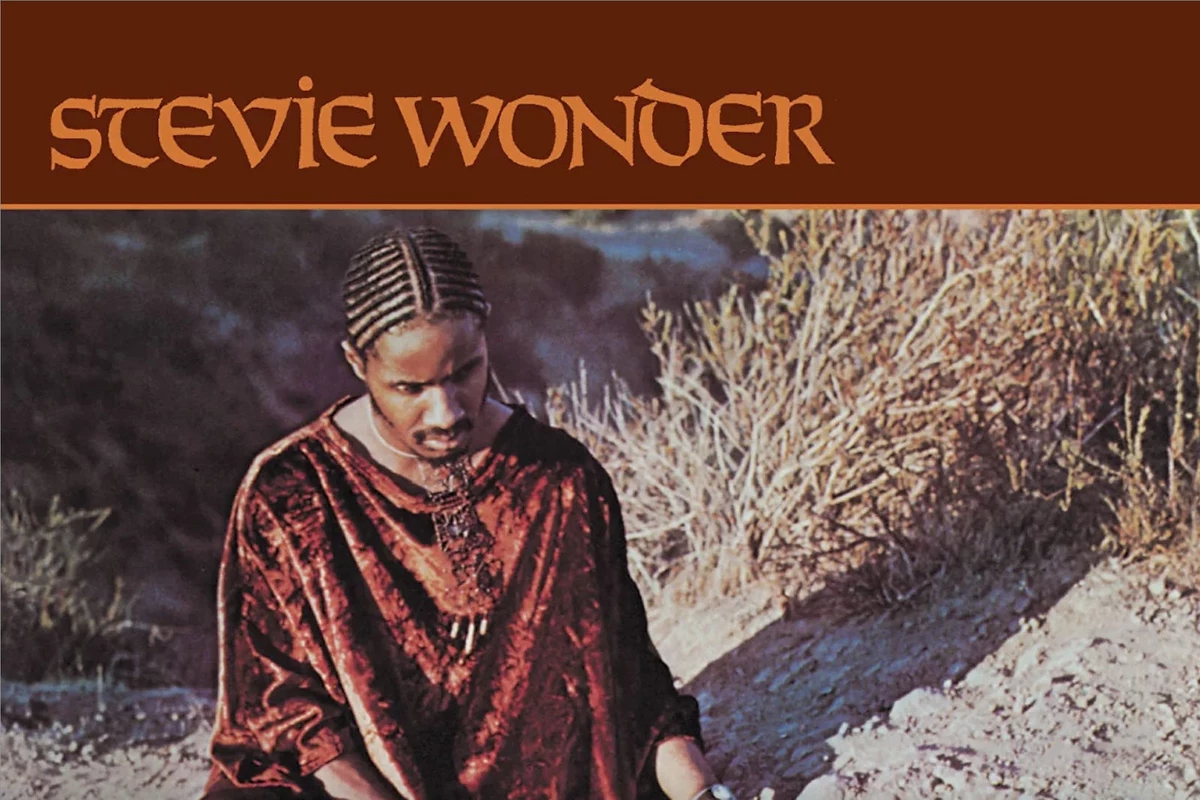

This brings a uniformity of music and concept that never existed before. Wonder is no longer the showboat of his youth or the sometimes-gimmicky experimenter of more recent LPs. With a cover image showing Stevie Wonder in a rare moment without his glasses, Talking Book instead showcased a new honesty to his music. The songs took a more introspective focus, as Wonder explored heartbreak, protest and ambition without regard for the old Motown fascination with hit singles.

Suddenly, his music was reflecting “the cry for civil rights, the urban Black experience and about who he was,” associate producer Robert Margouleff told The Atlantic in 2012. “He didn’t just write love songs, but he related to the world’s reality at that time. I thought he was a messenger. What he had to say was really important, and it’s proven to be that way.”

In a telling moment, the sunny album-opening No. 1 smash “You Are the Sunshine of My Life” was reportedly written before Wonder pulled away from Motown’s heavy-handed management for good. The paranoid funk of “Maybe Your Baby” immediately follows, and it’s much closer to the broader intent of the record, both in sound and vision. Wonder was suddenly prone to uncertainty amid the wreckage of his marriage to Syreeta Wright, and that brought a human dimension to everything.

Listen to Stevie Wonder’s ‘You Are the Sunshine of My Life’

“I don’t think you know where I’m coming from,” Wonder memorably scolded label execs in 1971. “I don’t think you can understand it.”

They didn’t. “Big Brother” boasted a political bent that was worlds away from earlier radio-ready favorites like “Uptight (Everything’s Alright)”: “I live in the ghetto, you just come to visit me ’round election time … I don’t even have to do nothin’ to you, you’ll cause your own country to fall.” But at the same time, “You and I” was simply shattering in its vulnerability.

“Blame It on the Sun” followed the same emotional trajectory. “The lyrics were very heavy,” Margouleff noted. “He was saying you have to blame yourself and not others for loves lost. He had heavy things going on.”

Wonder’s voicing, both personal and musical, provided the threads that sew everything together. His Fender Rhodes worked as a through line for most of the songs, but Wonder also dug deeper into new explorations of the TONTO synthesizer and, more crucially, the Hohner Clavinet. (Wonder signaled this groovy new direction on “Sweet Little Girl” from Music of My Mind when he whispered, “You know your baby loves you more than I love my Clavinet.”)

This instrument, and its specific sound, would come to define Wonder – and, to some degree, an era of R&B. In the meantime, it drove “Superstation.” Wonder built the album’s first chart-topping song atop a monstrous riff that Wonder swiped from Jeff Beck and then transposed onto the clavinet.

“I think that the reason that I talked about being superstitious is because I really didn’t believe in it,” Wonder told NPR in 2000. “I didn’t believe in the different things that people say about breaking glasses or the number 13 is bad luck and all those various things. And to those, I said, ‘When you believe in things you don’t understand, then you suffer.'”

Listen closely, however, and an anguished Wonder also seemed to be shaking his fist at the free-love era.

Listen to Stevie Wonder’s ‘Superstition’

“Tuesday Heartbreak” arrived amid a crashing tide of sound, with Rhodes and Clavinet replacing the more familiar strings then associated with R&B. Wonder brought in guest saxophonist David Sanborn to act as a ground wire while he blurted out unheeded pleas for reconciliation: “I wanna be with you when the nighttime comes / I wanna be with you ’til the daytime comes.”

“We got married at a very young age, and no one gave us a manual,” Syreeta Wright told the Burlington County Times in 2018. Their romantic ties were irretrievably broken, though they’d continue working together in a career that included her similarly quite personal Syreeta. “For me, the album was about my hope that maybe we could salvage our marriage. A lot of the vocals are coming from that space.”

Talking Book ultimately found hope among its uncertainties with the album-closing “I Believe (When I Fall in Love It Will Be Forever),” deftly bookending the LP with the unadulterated joy of “You Are the Sunshine of My Life.” This may be the wisest moment in an LP filled with them.

“It wasn’t so much that I wanted to say anything” with Talking Book, Wonder told NPR, “except where I wanted to just express the various many things that I felt — the political point of view that I have, the social point of view that I have, the passions, emotion and love that I felt. Compassion, the fun of love that I felt, the whole thing in the beginning with a joyful love and then the pain of love.”

Mission accomplished: “You Are the Sunshine of My Life” won a Grammy and “Superstition” earned two, while Talking Book became Wonder’s first Top 5 Billboard album hit. He’d end up reeling off eight in a row.

Top 25 Soul Albums of the ’70s

There’s more to the decade than Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder, but those legends are well represented.