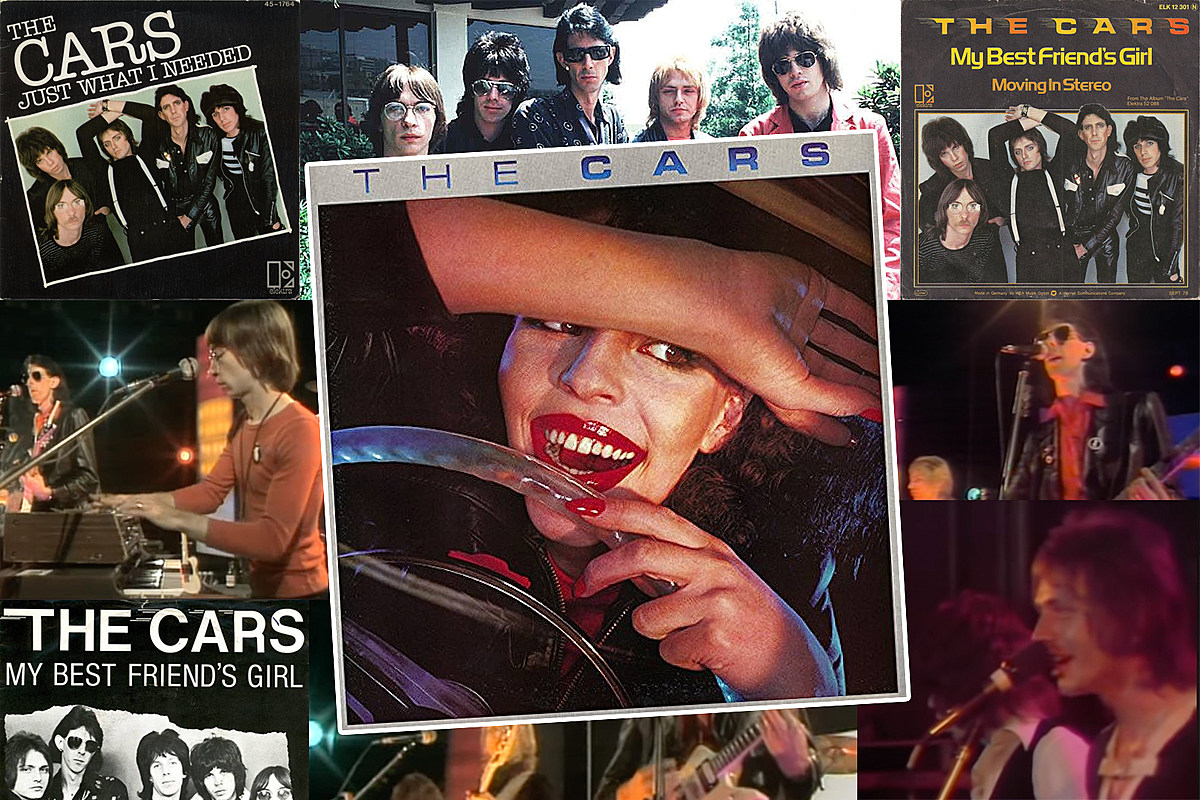

“We used to joke that the first album should be called The Cars’ Greatest Hits,” guitarist Elliot Easton has often said, including in the liner notes for Just What I Needed: The Cars Anthology in 1995.

Their self-titled debut came out on June 6, 1978, as a near-perfect amalgam for the times: It had new-wave cool and album-rock oomph. There were icy synths and overdriven guitar power chords. Technology and passion. The late Ric Ocasek’s lyrics flitted from ironic detachment to passionate angst, sometimes within the same song.

The Cars had the sound of the future but an embrace of the past, which is why its compositions and sonics are timeless. The LP sounds like a work of today no matter when you hear it.

Two of the songs, “Just What I Needed” and My Best Friend’s Girl,” were bona fide Top 40 hits, and “Good Times Roll” just missed. They joined four other album tracks as enduring radio staples, putting The Cars in the league of debuts by Boston and Foreigner as sprints straight off the starting block.

“The Cars had it all – the looks, the hoots, beat-romance lyrics, killer choruses, guitar solos that pissed off your parents,” the Killers‘ Brandon Flowers said during his spot-on induction speech for the Cars in 2018 at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland – their late bassist Benjamin Orr’s home town. “They were able to exist in that highly coveted sweet spot where credibility and acclaim meet huge commercial success.”

However, it was a long drive to The Cars. Ocasek and Orr were longtime friends who met in Cleveland, moved to Columbus, Ohio, and Ann Arbor, Mich., before settling in Boston during the early ’70s. Their first gambit there was a folk-rock group called Milkwood that released one album. Future Cars keyboardist Greg Hawkes played saxophone, then joined their next band, Richard and the Rabbits.

Ocasek and Orr later formed an acoustic coffeehouse duo whose repertoire included songs that would eventually become the Cars’. Like Hawkes, guitarist Elliot Easton was a Berklee School of Music student. He came on board for the more rock-oriented Cap’n Swing, which would become the Cars once drummer David Robinson of the Modern Lovers signed on.

“It took a minute,” Easton told this writer in 2020. “A lot happened before we made that [debut] album” – not least of which was the kind of old-school break that certainly doesn’t happen anymore: Maxanne Sartori, an air personality at WBCN who was also an advocate for Cap’n Swing, played songs from the Cars’ demo tape on her show nearly a year before the album would come out. Another station, WCOZ, followed suit and record companies took notice.

The new group chose Elektra over Arista, primarily because Elektra was a longtime haven for singer-songwriters and so had a greater need for a new wave band.

The Cars was recorded in London with producer Roy Thomas Baker, famed at the time for his work with Queen. Demos included on the 1999 deluxe edition of The Cars show a band with its creative affairs in order, but Baker added a spit-polish sheen that would make the songs even more radio-friendly.

“We never tried to make hits – ever,” Robinson said in anthology liner notes. “We just knew we had something different that sounded good. I probably thought that none of them were hits at the time.” Easton describes Baker’s approach as “get real balls but with clarity,” which led to some tension during the sessions.

“It was very intense,” Easton recalled. “He’s absolutely brilliant, you can’t argue with any of that. I will say he wore out several engineers who just ended up asleep under the board. They just couldn’t do it anymore. But he was up for everybody.”

Despite it all, this was a winning equation. The Cars reached No. 18 on the Billboard 200 and has been certified six times platinum. The LP insured a steady, hit-filled career until the Cars broke up in 1988, with short-lived reunions as the New Cars and then with the four surviving members 10 years after Orr’s death. The quartet played for the last time together at their Rock Hall induction. Ocasek passed away 17 months later, putting the Cars in storage – but not before creating an enduring legacy with this nine-track gem.

“Good Times Roll”

Sarcasm and cynicism drip from the opening track of The Cars, Ocasek’s take on the rock stardom he’d realized on a local level at the time: “Let the good times roll, let them make you a clown,” “if the illusion is real, let them give you a ride” and, of course, a reference to “rock ‘n’ roll hair.” Ocasek acknowledged “Good Times Roll” was “a parody,” and its deliberate gait was anything but good-time rock ‘n’ roll. That said, the track swings and serves as a microcosm of what’s to come – gritty guitar mixed with Hawkes’ synthesizer and Robinson’s electronic Syndrum accents. It’s a different kind of rocker, drawing out a line that the Cars would straddle throughout their career.

“My Best Friend’s Girl”

There was no actual best friend or girl who inspired the Cars’ second consecutive Top 40 hit. “I just figured having a girlfriend stolen was probably something that happened to a lot of people,” Ocasek later revealed. One of the tracks played as a demo on WBCN and WCOZ, “My Best Friend’s Girl” lets Easton loose with some rockabilly picking that butts up against Hawkes’ synthesizer hooks. It’s pure pop that came from a time when that wasn’t necessarily in vogue – yet “My Best Friend’s Girl” had more AOR swagger than others mining that field. It’s always mentioned in any discussion of the Cars’ best songs, and deservedly so.

“Just What I Needed”

The song that started it all was also part of the famed demo tape that Boston radio stations got behind. “I remember hearing ‘Just What I Needed,’ the first time I heard it, thinking, ‘Wow, that’s pretty cool,'” Hawkes said during a full-band promotional interview in 2000. He described the single as “nice and concise,” but it was also tremendously impactful and sly: The Cars slipped in an acknowledging nod to the Velvet Underground’s “Sister Ray” with the line “wasting all my time-time.” Along with “Best Friend’s Girl,” “Just What I Needed” established Orr as the Cars’ other principal vocalist. “If it needed to have a good voice, it needed to be Ben,” Ocasek remembers thinking in the 2000 interview. “This is a song that has a lot of melody and needs a good voice, so Ben should sing this one.”

“I’m in Touch With Your World”

Coming off a propulsive three-song start like that, the Cars had to down-shift at some point. The Cars does not stall on “I’m in Touch With Your World,” which was also the B-side to “Just What I Needed,” but the song was a substantial change of pace. This is artier, more ambient, halting and almost lo-fi in comparison to the punchy dynamics of its predecessors. “I’m in Touch With Your World” also gives Hawkes a chance to play around with a greater array of sound effects, but when the CD age came along you can bet this one was programmed out of a lot of replays.

“Don’t Cha Stop”

The Cars kicks back into gear at the end of the original Side One with a bouncy rocker that blends psychedelic and garage influences into three minutes of energetic cruise control. It’s also the album’s most straightforward love (or lust) song, sounding a bit out of place but at least ensuring some libido existed within Ocasek’s droll countenance.

“You’re All I’ve Got Tonight”

Robinson’s thundering, flanged tom toms introduce a second side plays like a suite, with each song (all four minutes or longer) bleeding into the other in some form and taking us on a journey of emotional tumult. “You’re All I’ve Got Tonight” was The Cars‘ heaviest rocker, as Easton puts a little metal into his tone while stretching out his solos in a manner that almost feels like jamming. Meanwhile, Ocasek lets that noise in his head distract him enough to get through what sounds like a dire romantic situation: “You can make me, I don’t care – and you can fake me, I don’t care. And you can love me just about anywhere. It’s alright, ’cause you’re all I’ve got tonight”).

“Bye Bye Love”

With just a second’s silence, Ocasek waves farewell with the Cars still in high gear. “Bye Bye Love” was another Easton showcase, and one the band knew well. This was part of a Cap’n Swing demo even before the Cars formed, with Hawkes adding the keyboard lines between the verses. The cannon-shot dynamics pull back just enough to give “Bye Bye Love” an additional hard-rock punch that serves the narrator’s triumphant vindication.

“Moving In Stereo”

The Cars downshifts yet again, but this time it works well as both respite from the fusillade and a nice turn into nocturnal ambience. Co-written by Ocasek and Hawkes, “Moving In Stereo” is the longest track on the album at 4:46. The song displays an influence from early Roxy Music, with a meandering gait that – to the band’s credit – never wears thin. Its insistent, halting rhythm is also an effective bridge between the LP’s heavy predecessors and the calm that’s coming up behind it. “Moving In Stereo” stands well on its own, still it’s hard to listen to and not think of actress Phoebe Cates’ memorable scene from Fast Times at Ridgemont High.

“All Mixed Up”

“Moving In Stereo” gentle merge into The Cars‘ concluding track is a beautiful. “All Mixed Up” starts with the wonderfully subtle hint of a groove and plenty of ebb and flow that lets the band members weave through their parts without getting in each others’, or the song’s, way. Each performance here is masterful – including Hawkes’ sax solo at the end – and those stacked chorus vocals remind us that, oh yeah, the band’s working with Queen’s producer. “All Mixed Up” may be about a woman asserting a degree of control over her mate, but the lyrical promise that “everything’ll be alright” also applies to the experience of listening to The Cars.

Top 40 New Wave Albums

From the B-52’s to XTC, Blondie to Talking Heads, a look at the genre’s best LPs.