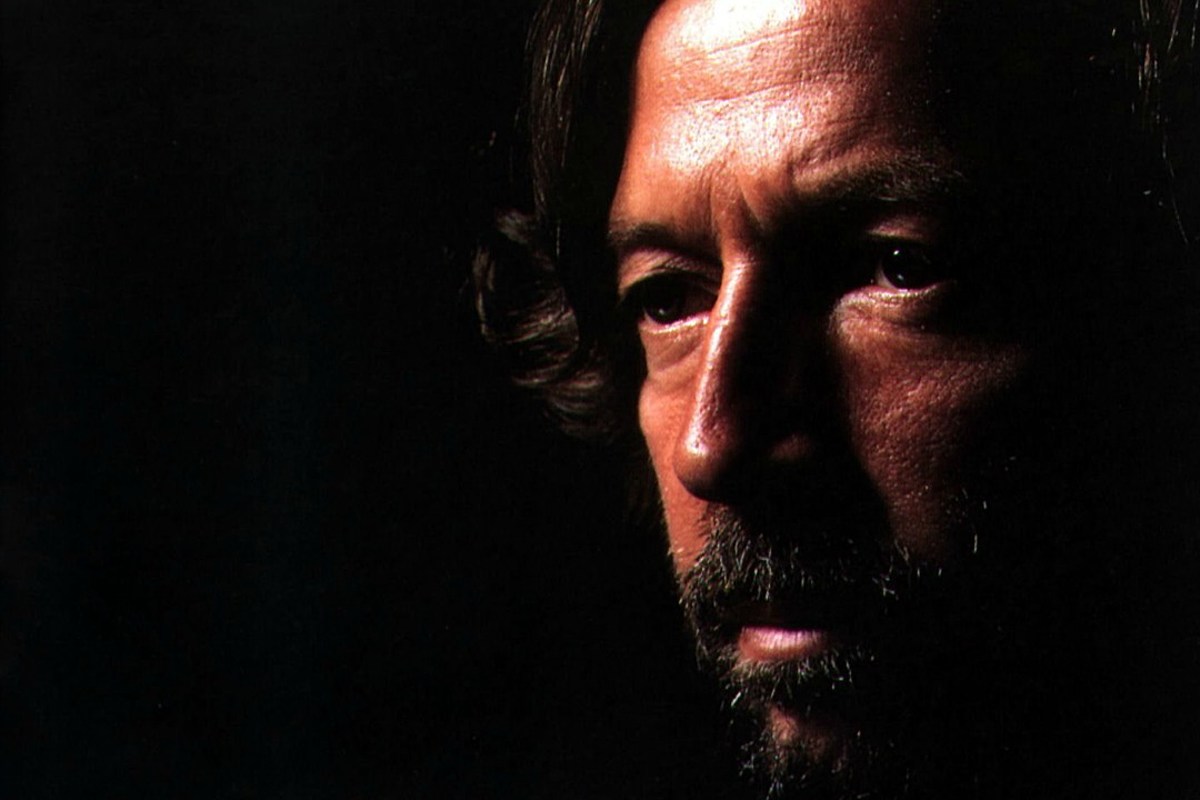

Eric Clapton sold his share of records and had his share of hit singles during the ’80s, but to say it wasn’t his best decade would be a polite understatement.

From 1981’s Another Ticket through 1983’s Money and Cigarettes, 1985’s Behind the Sun and 1986’s August, the guitarist once hailed as God led listeners on a sleepy crawl down from the blues-inspired heights of his early career into an adult contemporary valley littered with synthesizers and beer-commercial anthems.

Not that his fans weren’t willing to forgive a certain comedown from Clapton’s classic period. His struggles with substance abuse prompted a trip to rehab toward the start of the decade – inspiring the title of Money and Cigarettes, as he felt like that’s all he had left after he went through the program. And if his ’80s efforts tended toward the sleekly competent side of the rock spectrum, they still made room for periodic flashes of past glories, however brief or slickly produced.

The decade also brought Clapton into the orbit of Jerry Lynn Williams, a Texas songwriter enlisted by Warner Bros. after label execs listened to the first version of Behind the Sun and insisted he seek outside help for new material. After agreeing to meet with Williams, Clapton came away with a stack of Williams songs that included the hit “Forever Man,” as well as several partnerships that would last for years – and produce some of his most successful singles of the era.

“Now, I never wanted hits; I never wanted to have to deal with that,” Clapton explained in 1990. “But faced with the prospect that [Behind the Sun] would be a flop, that it would be hard to promote and that it was self-indulgent, I agreed to re-record a third of it. So, Warners sent me some Jerry Williams song, which I really loved, and off I went to Los Angeles. There, in the studio, I met [keyboardist] Greg Phillinganes and [bassist] Nathan East. They’d been hired to play on the songs by the president of Warner Brothers, Lenny Waronker. I thought they were great.”

Phillinganes and East were featured heavily on August, which sold well despite a relatively low chart peak and rather lukewarm reviews. Clearly not wanting to disrupt a good thing, Clapton retained his creative nucleus for the follow-up, which started coming together in the studio in early 1989. While Williams didn’t contribute any songwriting credits to August, he’d end up featured very heavily on its successor.

Titled Journeyman and released on Nov. 7, 1989, Clapton’s 11th studio LP didn’t fully deviate from the radio-friendly approach he’d taken for Behind the Sun and August, but it was a clear step back from the adult-contemporary abyss. That change was apparent from “Pretending,” an album-opening, Williams-penned mid-tempo number with just enough middle-aged swagger and stinging Slowhand guitar to raise fans’ flagging hopes for a record with a little more bite.

On the whole, those hopes were rewarded. In fact, although Journeyman failed to produce a pop Top 40 single, it sent four tracks to the Top 10 of the Mainstream Rock chart (“Pretending” and “Bad Love,” both of which hit No. 1, as well as a No. 9 cover of the blues standard “Before You Accuse Me” and the No. 4 “No Alibis”). The album didn’t lack for sales either: its double-platinum certification gave Clapton his biggest hit in more than a decade.

More importantly, while Clapton’s material had always been solidly grounded in the blues, Journeyman demonstrated a renewed focus on those roots – not just through “Before You Accuse Me” and audibly affectionate covers of Ray Charles‘ “Hard Times” and the Leiber & Stoller classic “Hound Dog,” but also through an overall sound that, while far from stripped down, scrubbed away some of the gloss that clogged Behind the Sun and August. He sounded connected to the music in a way he hadn’t for quite some time.

Over the decades, Journeyman proved a pivotal point in Clapton’s discography – an album that, while it delivered no shortage of radio-friendly material, also signaled his waning interest in pursuing pop hits. And although the next few years saw Clapton’s popularity skyrocketing, thanks to his intensely personal single “Tears in Heaven” and massively successful Unplugged LP, they also found him drifting from the guitar heroics that defined his earlier work.

In fact, he’d take five years to deliver a proper follow-up to Journeyman, and when he did, the result was the straight blues project From the Cradle, a live-in-the-studio LP that tried to use Clapton’s renewed clout to shine a light on artists like Lowell Fulson, Willie Dixon and Tampa Red – names that might not have meant anything to many of the three million people who bought the album, but whose songs helped form a musical bedrock for countless rock acts.

From the Cradle was the first in a series of blues-influenced albums, and though Clapton continued to release rock records, they came fewer and farther between, dropped into the lengthy spaces between projects like the B.B. King duet LP, Riding With the King, the Robert Johnson tribute, Me and Mr. Johnson, and 2014’s The Breeze: An Appreciation of JJ Cale. Those pop hits dried up along the way; Clapton’s last Top 40 single, “My Father’s Eyes,” arrived in 1998.

Not that he seemed to mind. Taking an increasingly casual approach to record-making in general, Eric Clapton seemed eager to embrace elder statesman status and use his position to help introduce listeners to the artists who’d inspired him as a young man – particularly blues artists.

“I still feel protective towards the blues,” Clapton said in the months after Journeyman was released. “It’s a maligned art form and I get angry when I feel people are taking it too lightly. I go back to the blues because of its rawness. It’s got more energy and vitality than anything I can think of. Most musicians who’ve been around will accept that the blues is the bottom line. It’s always given me more out of life than sex, booze or any kick you can think of.”