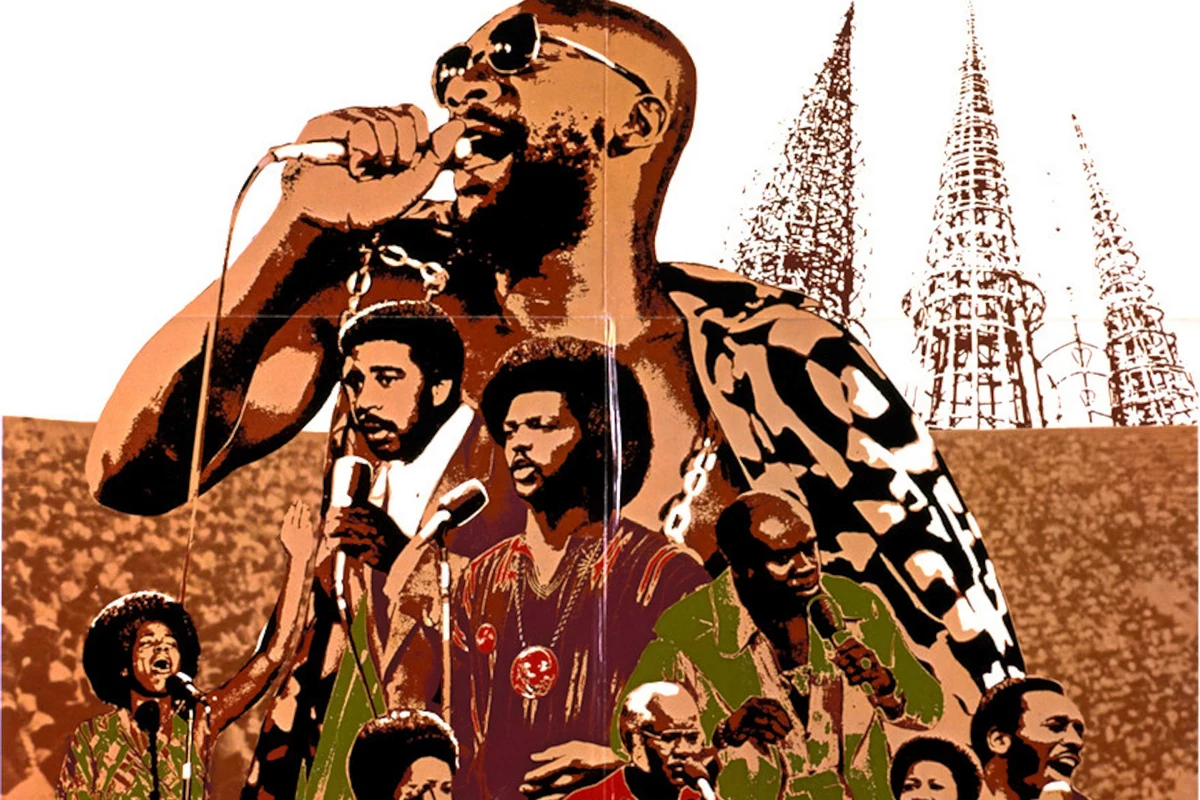

The producers of Wattstax had a problem when it came to the industry’s rating system.

Intended for family audiences, their movie followed along as multiple Stax Records-affiliated R&B and soul legends took the stage in August 1972 at the sprawling Los Angeles Coliseum to commemorate the Watts riots, with topical man-on-the-street interviews interspersed throughout. Some profanity crept into these responses, however, and that led to an R rating from the MPAA.

Wolper Productions’ response was retroactively quite ironic. They created marketing material that suggested Wattstax was “Rated ‘R’ because it’s real.”

Not exactly.

The subject matter of those interviews, and even some of the people, had been predetermined. One of the featured actors was Ted Lange – who later found success on TV’s The Love Boat. That was just the beginning of the postproduction work that radically reshaped this legendary concert in director Mel Stuart’s film, which premiered on Feb. 4, 1973.

“We went down and spent the day and shot the concert,” Stuart later told The Baltimore Sun. “And everything seemed to go very well. Then we brought the footage back and I said, ‘We have a concert. That’s not good enough. A concert is boring, there are so many of them, who cares?'”

Eruptive Coliseum performances by Rufus Thomas (“Do the Funky Chicken”), the Staples Singers (“Respect Yourself”), Eddie Floyd (“Knock on Wood”) and Albert King (“I’ll Play the Blues for You”) were among the highlights. But Stuart also added a series of subsequently recorded clips from artists who weren’t in attendance – including Little Milton, Richard Pryor and Johnnie Taylor, among others.

Watch a Trailer for the Expanded Edition of ‘Wattstax’

A suitably decked-out Isaac Hayes also closed the film with another postproduction clip, after Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer officials confirmed that the contract for his songs from the movie Shaft prevented further cinematic use until 1978. Unfortunately, this wasn’t revealed until after the premiere of Wattstax, meaning Hayes had to be called in from a tour of the Netherlands to quickly film a replacement song before the movie saw wider release. He dashed off a take on his next scheduled single, “Rolling Down a Mountainside.”

Even the LP version, titled Wattstax: The Living Word and released in January 1973, included studio recordings of the Staples Singers’ “Oh La Di Da” and Floyd’s “Lay Your Loving on Me” with overdubbed applause. None of it took away from what remained; it just wasn’t always all that “real” – at least from the moviegoer’s standpoint. For people like Hayes, already a symbol for racial justice and Black pride, Wattstax represented a much, much bigger idea.

“There was hope in that film and everything that we aspired to be,” Hayes told NBC in 2004. “It was a great day and it went off without incident. We didn’t realize how huge it was until it was all over and the film was cut together and shown.”

Pryor’s edited-in monologue ended up holding the whole concept together. “I said, ‘We need somebody like the chorus in Henry V,” Stuart told the Sun. “Well, of course, nobody knew what I was talking about, but I said, ‘He describes what’s going to happen.'”

Still, few people saw Wattstax at the time – even though the film version of a concert called the “Black Woodstock” was presented at the Cannes Film Festival and then earned a Golden Globe nomination.

Listen to Isaac Hayes Perform ‘Shaft’ at Wattstax

At the time, it was considered too political, too controversial – and, yes, too Black. “It did fall through the cracks,” Stax Records president Al Bell told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2004. “It was kicked to the curb.”

The film “did very well in Black neighborhoods,” Stuart told Mix Online, even though it quickly disappeared elsewhere. “A lot of Black people have seen it, but it generally hasn’t made it into the mainstream because of the language. It’s become a sort of cult thing – because it probably is, in all honesty, the best concert film about Black music that’s ever been made.”

Subsequent restored and remastered versions would include the music from Shaft, and that only underscored how much more involving the original live performances before a 112,000-strong audience always was.

Finally, everyone got to see emcee Jesse Jackson’s immortal introduction of Hayes’ “Theme From Shaft”: “Do we want to see Isaac Hayes? Brothers and sisters, we are about to bring forth a bad, bad … .” Instead of uttering the expected oedipal expletive, Jackson jokingly added, “I’m a preacher, I can’t say it!”

Then Hayes, who’d just been chauffeured into the Coliseum in a lime-green station wagon, let his regal cape drop. He was in gold chains – something that felt symbolic of Black people’s freedom struggle but also suggestive of the economic opportunity they all hoped one day to enjoy.

What better culmination of a moment that Lange described as a “celebration of Black people being Black”? “Stax Records represented a closer connection to the average man, while Motown was trying to infiltrate the establishment,” he told the Associated Press. “Stax was rejoicing in the difference in who we are, and that’s what you see in the film.”

Top 25 Soul Albums of the ’70s

There’s more to the decade than Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder, but those legends are well represented.