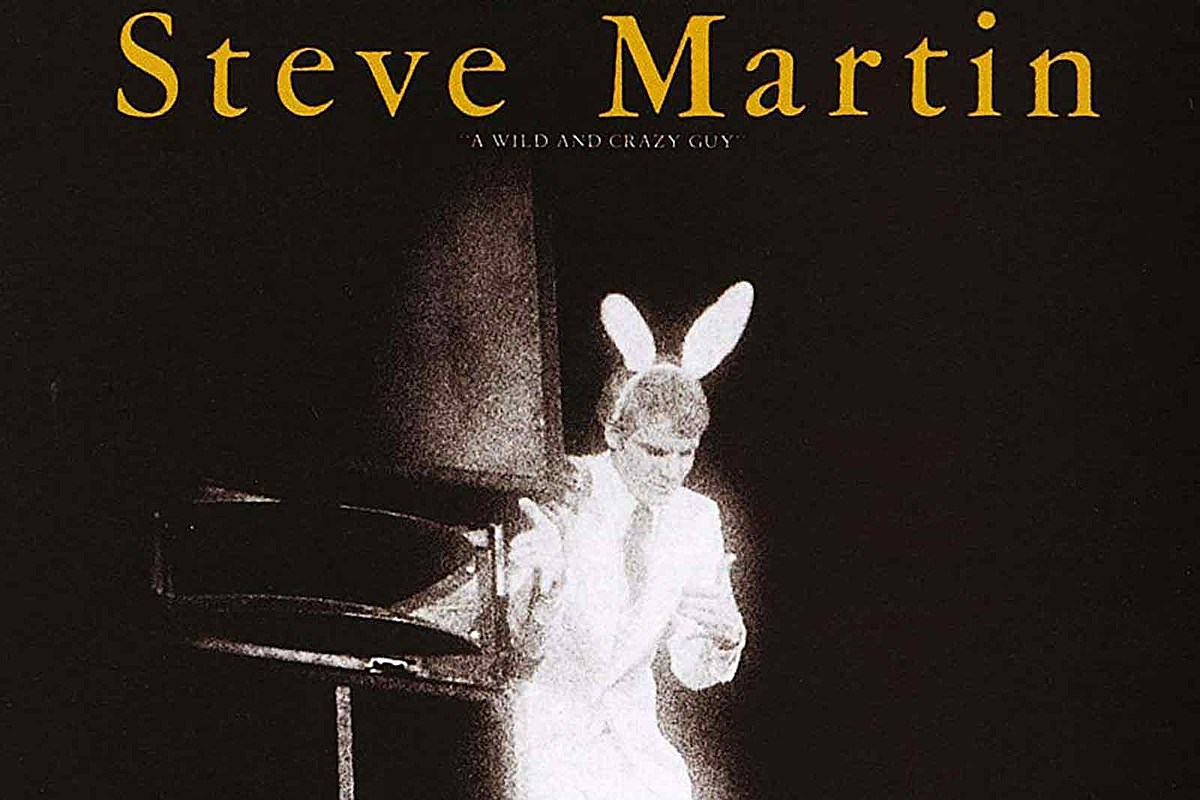

Steve Martin had been honing his singularly silly stand-up act for a decade before the world truly caught on. That’s not surprising, as Martin’s comic persona was itself a put-on, a layered deconstruction of showbiz and stand-up that required his audience to perform a demanding mental calculus, all while the white-suited, bunny-eared Martin performed some of the most outwardly silly schtick imaginable.

But catch on the world did, with Martin’s appearances on the upstart late-night comedy series Saturday Night Live branding his deceptively brainy comedy into the public consciousness to the extent that SNL’s ratings routinely rose by a million or more viewers every time Martin was in the house. His first comedy album, 1977’s Let’s Get Small, went platinum and won a Grammy Award, making Martin’s inevitable follow-up, A Wild and Crazy Guy (released in October 1978), a critical and commercial sure thing. It was both, with A Wild and Crazy Guy doubling the sales of its predecessor (and reaching No. 2 on Billboard), Martin receiving another Best Comedy Album Grammy and the comic embarking on a stand-up tour whose wild success is documented in a midset shift on the album itself.

Beginning at the more intimate setting of San Francisco’s Boarding House, where Martin had honed his craft for years, the record’s two sides undergo a shift partway through the album’s fourth track, “A Wild and Crazy Guy.” Martin begins by feigning irritation that a new law requires him to make a midshow financial disclosure, running through his take-home from the relatively meager admission fee to the Boarding House before speculating that, if he charged $800 a ticket, he could retire. “This is what I’m shooting for,” notes Martin smugly, “One show — goodbye.”

Steve Martin’s Comedy Routine

The resulting Boarding House laughter then segues seamlessly into a rising, near-hysterical whooping, as the second half of the album shifts to Colorado’s cavernous Red Rocks Amphitheater, a leap not only of venue but of style. The Boarding House material is, while still inimitably Martin in its wacky string of bits and asides, more playfully intimate. Martin begins his set by immediately deconstructing the very thing he’s been doing for two weeks at two shows a night, deadpanning, “I think there’s nothing better for a person than to do the same thing over and over for two weeks.”

The Boarding House material allows Martin to expand upon his role as a paid comic, his insincere bursts of show business patter and desperate segues aping the flop sweat of a comedian terrified to lose his crowd ceding occasionally to a more knowing and mischievous tone. When Martin plays up his intellectual pretensions by running through his then-fictitious life as a renowned author, he rattles off works such as “Mind Gone Haywire,” “The Apple Pie Hubbub” and “Ceremony for a Fat Lip.” (Martin also prefigured Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure by airily mispronouncing a certain philosopher as “So-crates.”) He also expertly shuts down a heckler, does some offhand crowd work and generally works the modest-sized room like the pro he is. Whipping out his trusty banjo at one point for an impromptu bit of noodling, Martin further skewers his pretensions by boasting, “It’s not often that you can pay $4 to see someone jack off like this.”

READ MORE: How the ‘Sgt. Pepper’ Movie Flopped

When the album abruptly shifts to Red Rocks, Martin’s act shifts gears, too. Beginning with a mock-modest, “For me??” in response to the much larger audience’s rapturous greeting, Martin becomes the outsized, crowd-pleasing big-shot persona the sold-out amphitheater demands. It’s only appropriate that A Wild and Crazy Guy expands into this huge space: Steve Martin by this point is a comedy rock star. And, like a rock concert, the Red Rocks audience expects the hits, with Martin trotting out his unnamed “wild and crazy guy” foreign character, knowing full well that everyone in attendance now associates his on-the-make, boundlessly and unaccountably confident character with Georg Festrunk, the wildly popular Saturday Night Live version of the character.

Listen to Steve Martin’s ‘A Wild and Crazy Guy’

Martin being Martin, his greatest-hits approach to stadium comedy is still festooned with winking deconstruction. Taking on the implied audience desire for him to repeat old material, Martin fakes affront, proudly proclaiming that he will not do any Let’s Get Small material before berating the crowd with the exaggerated “Excuuuuse me!” catchphrase from that very album. Martin also kicks off this latter set by cleverly luring his ravenous crowd into a trap, ending his crowd-baiting call-and-response “nonconformists’ oath” by forcing the lavish audience to break up midway through the dutiful chant, “I promise not to repeat things other people say!” That the set closes with an elaborate performance of the SNL-introduced novelty hit “King Tut” (backed by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, billed as the Toot Uncommons) is the sort of big-finish show business crowd-pleaser designed to send an audience home satisfied.

Steve Martin Leaves Stand-Up Comedy

He’d leave stand-up comedy behind just a few years later. For the intensely private and deeply curious Martin, the inevitable trappings of phenomenal success as a public figure chafed. (Martin later revealed he was prone to panic attacks and wrote about the bewildering grind of secret backdoor entrances to stadiums swarmed with bellowing fans.) Meanwhile, as Martin later wrote about in his 2007 memoir of his stand-up days, Born Standing Up, his approach to stand-up comedy was always about reinvention and deconstruction.

Joke about “So-crates” though he did, Martin was an insatiable polymath, an avid intellectual and aspiring musician, art collector, playwright and author. Stand-up comedy, for Martin, was an old, beloved puzzle box to be fiddled with, insightfully and delightfully mocked for its conventions and cliches — and ultimately solved. In a 2008 interview with NPR’s Terry Gross, Martin, by then comfortably ensconced in his other wide-ranging interests, noted of his time in the stand-up spotlight, “But the act essentially, besides all the jokes and bits and everything, was conceptual. And once the concept was understood, there was nothing more to develop.”

READ MORE: When Steve Martin’s ‘King Tut’ Became a Surprise Hit

Martin would ride the ebbing stand-up wave for two more albums. 1979’s Comedy Is Not Pretty retreated to “mere” platinum status, its Grammy-nominated track listing interrupted with Martin’s narration of a story from his first book, Cruel Shoes, and a straight-ahead banjo instrumental. His final comedy record, 1981’s The Steve Martin Brothers, expanded the portrait of a person with one foot out of the comedy club door, the second side almost entirely made up of banjo. The record reached only No. 135 on the Billboard chart, with Martin claiming he’d never do stand-up again. His 2022 doubles act with pal Martin Short is less him reneging on that promise and more an affectionate return to the performing stage on his terms.

‘Saturday Night Live’ Movies That Were Never Made