Amid the geniuses, stylists, and show people that made up the Sixties Motown roster, Stevie Wonder may have been the most purely original singer. Even before he asserted himself musically with his classic run of albums in the 1970s, Wonder was already putting his distinct stamp on his music — and all of Motown’s. For one thing, he was a budding studio rat from the minute he made the roster: “Knockin’ the pianos out of tune, bustin’ the heads on the snare drums, he was one pest,” Andre Williams, an early producer, later said. “Matter of fact, he was barred from the studio, because he’d go in when nobody was there and mess all the instruments up.”

His first hit was a fluke, albeit a huge one: “Fingerprints Pt. 2” spent three weeks at number one on Billboard’s Hot 100. Though it took some time for other Wonder songs to join it, it was also a bellwether: This kid had universal appeal. Though he didn’t hit it big again until late 1965, with “Uptight,” Wonder became Motown’s weather vane — absorbing Bob Dylan, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Stax, and foregrounding them in his own music. As the Sixties ended, Wonder was co-writing and beginning to co-produce an increasing amount of music, including for other artists.

“I used to play on a lot of gospel sessions,” Wonder would later say of those days — just one of the many kinds of music in whose styles he would later write classic songs, many of them on this list. It’s not complete, of course — 50 is a small number, and Wonder specializes in thematically and musically cohesive albums, at least up through 2005’s A Time for Love, his last full length, almost 20 years ago. (There have also been a few digital singles since then.)

This list, then, basically keeps it to Stevie songs from Stevie albums. Wonder’s guest harmonica spots (Chaka Khan’s “I Feel 4 U,” Elton John’s “I Guess That’s Why They Call It the Blues”), songwriting (Smokey Robinson and the Miracles’ “Tears of a Clown,” Aretha Franklin’s “Until You Come Back to Me”), producing (the Spinners’ “It’s a Shame,” Rufus and Chaka Khan’s “Tell Me Something Good,” Jermaine Jackson’s “Let’s Get Serious”), and his prominent placement on event records such as “We Are the World” and “That’s What Friends Are For” could, by themselves, all fill another list.

Wonder was, and remains, a startlingly complete artist — fluent in many musical styles, politically sharp and romantically disarming, always identifiably himself on any instrument. His ebullience has always appealed to kids: He played “Supersition” on Sesame Street and helped usher hip-hop into middle America on The Cosby Show. But as this list amply demonstrates, Wonder wrote more good political songs than any other 1960s-identiifed songwriter, Dylan included. (Wonder, of course, also sang, and helped redefine, one of Dylan’s.) And Wonder stands as American pop’s most effective activist: Martin Luther King Jr. has a holiday named for him in large part due to Stevie’s lobbying efforts.

As long as it’s been since we had a real Stevie Wonder album, we surely have yet to hear the last of him. Here are 50 reasons we’ll never stop listening.

-

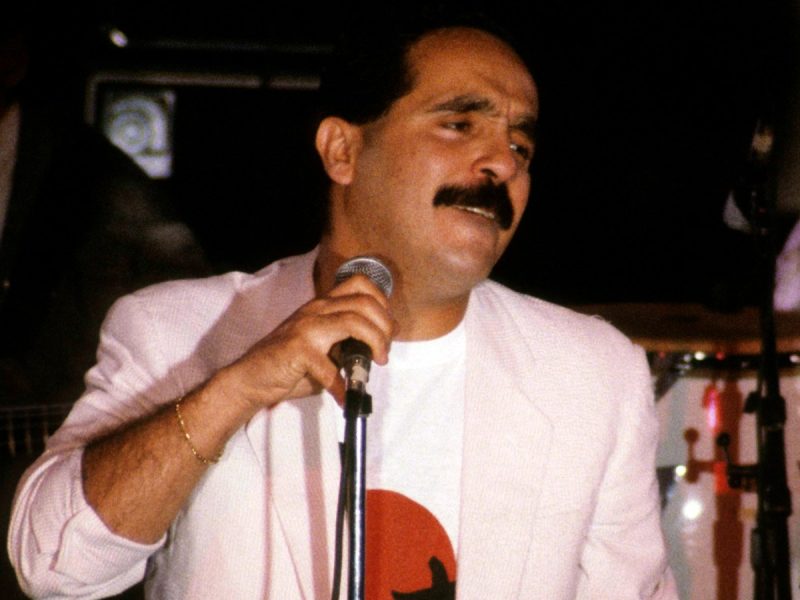

‘Part Time Lover’

Image Credit: Jim Steinfeldt/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images In the mid-1980s, the question on much of the music business’s mind was “Where’s the next Stevie Wonder album (not compilation, not soundtrack), already?” Answer: It was being tinkered with endlessly: “It’s the kind of thing with him where you get too big, you panic,” said Ray Parker Jr., the Eighties hitmaker who’d played guitar with Wonder in the Seventies. “He’s a little scared. He’s always going back to re-do something.” But that perfectionism paid off. When Wonder’s In Square Circle emerged in 1985, its lead single, “Part Time Lover,” about a cheating husband who discovers his wife is doing the same, hit Number One with preternatural ease — perfect for a song whose streamlined groove suggested cruise control.

-

‘Superwoman (Where Were You When I Needed You)’

Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images Stevie meets women’s lib, as it was then known popularly, and finds it a little wearying. This sentiment hasn’t aged all that well, but it’s an honest attempt to grapple with the changing sexual mores of the time, and its melodic contours catch and hold. Vince Aletti reviewed Music of My Mind for Rolling Stone in April 1972: “His first outside the Motown Superstructure (i.e., without Motown arrangers, producers, musicians, studios, or supervision of any kind). This is an important step, especially when it’s taken with such strength and confidence as it is here.”

-

‘Race Babbling’

Image Credit: Michael Putland/Getty Images This fast, insinuating synth jam — part of the exploratory Journey Through “The Secret Life of Plants” soundtrack — is a key link between the Motown legacy and that of another generation of Black Detroiters: techno. The aqueous, limber funk of “Race Babbling,” dabbed with sleekly flaring horns, flexes an expanded sense of musical possibility that prefigures Eighties and Nineties innovators like Juan Atkins and Underground Resistance — rhythm-first, patterns upon patterns, vocals de-centered, a unique sound picture as well as groove the ultimate goal. Its borderless vastness affected more established musicians as well. Yes frontman Jon Anderson recalled that upon hearing “Secret Life of Plants,” “I sat down and cried.… It was like, ‘Oh, God. Somebody thinks and makes music correctly — in the way that music should be and it’s part of your experience, part of your life’s challenge.’”

-

‘Contusion’

Image Credit: Jim Britt/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images In 1975, Stevie reupped his Motown contract, signing a 120-page, seven-year agreement good for $13 million. His first record on it, Songs in the Key of Life, was massive in every way: 86 minutes that overspilled two LPs onto a bonus seven-inch EP, four U.S. hit singles (with “Isn’t She Lovely” charting outside of the States), the Number One album in America for 14 weeks. It was also Wonder’s most musically expansive work yet, and the proof showed up on Side One. “Contusion” was a straight-up jazz-funk jam, a pop Weather Report tune, tightly wound and diamond hard, played with relish by Wonder’s touring group: guitarists Michael Sembello (yep, the “Maniac” guy) and Ben Bridges, keyboardist Greg Phillinganes (yep, the Thriller guy), bassist Nathan Watts, and drummer Raymond Pounds. (They’d been playing it live since 1974.) Stevie plays multiple instruments on it, of course, but even without a lead vocal (there are some background doot-doot‘s), “Contusion” said plenty about Wonder’s ambition and reach. The title said something for his humor, as well — a contusion was his official injury from the summer 1973 auto accident that had nearly ended his life.

-

‘Blowin’ in the Wind’

Image Credit: John Kisch Archive/Getty Images This record was a shock — not least to Berry Gordy, Motown Records’ founder and president, who didn’t want it released, went ahead with it anyway, and watched it go to Number One on the R&B chart and Top Ten on the pop chart. Two reasons: Motown didn’t release “political” songs, period, and it also didn’t put cover versions on the A side of singles — if it had been any other songwriter than Bob Dylan, then in the midst of altering pop’s lyrical landscape, it would have seemed like a prima facie insult to the writing staff. Instead, Stevie and his early Motown mentor Clarence Paul’s performance of it as a gospel call-and-response, à la Sam Cooke, made the record utterly relevant to the label’s upward-and-onward image. Paul answers Wonder with stirring conviction and gets the record’s best moment: “Too many years have gone by already now, Stevie.”

-

‘High Heel Sneakers’

Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images Recorded live at Paris’ Olympia during the Motortown Revue’s European tour in the spring of 1965, this was a cover — Tommy Tucker had a hit a year earlier on Chess Records with it, and it became an instant blues standard. But that’s not how Stevie treats it. His voice has changed — the near-squeakiness of early singles like “Little Water Boy” is gone, replaced by the knowing, teasing huskiness that would become his hallmark — and he and the band rev up and flatten out the tempo, turning it into a chugging rock & roller tailor-made for a surf movie. Wonder appeared in two: Muscle Beach Party and Bikini Beach, both in 1964. On the B side: a cover of Willie Nelson’s “Funny How Time Slips Away” that prefigures what Stevie would do with “Blowin’ in the Wind” a year later. (Not his only country dalliance, either: He opened shows in 1984 with what a Down Beat reporter described as “a letter-perfect rendition” of Ernest Tubb’s honky-tonk country classic “Walking the Floor Over You.”

-

‘Black Man’

Image Credit: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images Because creating enough music for a double LP with bonus EP wasn’t ambitious enough, Stevie Wonder made sure Songs in the Key of Life was rife with overt history lessons—a conscious (and successful) effort to reach the curious minds of his youngest fans. Hence the jazz-great roll call of “Sir Duke” and the long finish of this lengthy jam, a classroom call-and-response over its bubbling groove. (Teacher: “Who was the First American to show the Pilgrims at Plymouth the secrets of survival in the new world?” Students: “Squanto, a red man!”) Over eight minutes long, the record was also purpose-built for disco DJs, a key constituency in Wonder’s audience: A 1974 Billboard report on the rising discotheque scene refers to Stevie as “the king of the discos. His music really gets played there.”

-

‘Contract on Love’

Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images There was no getting around how talented he was, but when Stevie first signed to Motown, it took some time to figure out his niche. First, they tried novelties like “I Call It Pretty Music but the Old Folks Call It the Blues,” but this doo-wop pastiche was a big step forward: “That made a little noise,” Stevie later told Rolling Stone’s Ben Fong-Torres. It didn’t land on the national charts, but “Contract on Love” — a hard-stomping early collaboration by Brian Holland and Lamont Dozier (with Janie Bradford here) before being joined by Brian’s brother Eddie — prefigured the Supremes hits to come. But the song’s lyrics can also be read as a jibe at a workplace where you got it in writing or you didn’t get it at all: “Sign it! Sign it! Sign — the contract of love.”

-

‘A Place in the Sun’

Image Credit: CA/Redferns/Getty Images How did Motown respond to the surprise hit of “Blowin’ in the Wind”? By ordering up another socially conscious song for Stevie’s next single, this one written in-house. Rather than allusive in the Dylan manner, “A Place in the Sun” has more in common with Curtis Mayfield’s politically aware hits for the Impressions. It’s schmaltzier than Mayfield or Dylan; the glee-club vocal backing and Tijuana horns suggest Nashville. But Stevie’s newly mature voice makes the corn credible; his vocal soars higher than the strings.

-

‘Sweetest Somebody I Know’

Image Credit: Kevin Mazur/WireImage At a certain point, you figure someone like Wonder might just start phoning it in. But, no, he takes so long to record albums because his standards are exacting, and because as recently as his most recent studio album, he was still audibly pushing himself vocally and compositionally. Sure, “Sweetest Somebody I Know” lives up to its title by being a little sugary. But Stevie’s a master confectioner, and this Latin-flavored ballad, led by flamenco guitar and perfumed with humid strings, is a testament to his never-ending search for perfection — a piece of work whose ebullience still startles.

-

‘Love Having You Around’

Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images Stevie Wonder’s early Seventies are one of the great artistic-growth stretches on record — not least because he got his hands on advanced technology. “Maybe a year and a half ago, I couldn’t have done these kinds of tracks,” Wonder said of Music of My Mind, exulting about the power of the Moog synthesizer. “I feel it is an instrument and is a way to directly express what comes from your mind. It gives you so much of a sound in the broader sense. What you’re actually doing with an oscillator is taking a sound and shaping it into whatever form you want.” On Mind’s opening track, that form was personal, intimate, warm, the perfect expression of Wonder’s new, ruminative, adult style. “Love Having You Around” glows with adult eros, and the extended, overheard-voices coda displays his new studio obsessiveness with a mischievous wink.

-

‘That Girl’

Image Credit: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images A new Stevie Wonder album was such a hot commodity in 1982 that the four new additions to the otherwise-a-hits-collection Original Musiquarium helped the album shoot to Number One almost immediately, and this “hard slow slink of a single,” in the words of a Musician review, was an instant smash. In an era when the charts were packed full of his old sidemen — Ray Parker Jr.’s hit streak; Michael Sembello’s “Maniac”; one-time drummer Ollie Brown, as half of Ollie and Jerry, with “Breakin’ … There’s No Stopping Us” — Stevie sounds completely at ease in this sparse, synth-led future that he, more than anybody else, had made.

-

‘Gotta Have You’

Image Credit: Mick Hutson/Redferns/Getty Images “Oh, Stevie hit it out of the park,” Spike Lee told Slate when interviewed about Wonder’s soundtrack for his 1991 film Jungle Fever. “He would send in a song and tell me, ‘Here’s where I think it should go in the film, but if you want to move it around, go ahead.’ Every song he wrote for the film ended up in the film. There was no extra material lying around.” Not every song landed — the title track’s trite lyrics are justly notorious — but this lean groove fruitfully continues the conversation between Wonder and his new jack swing progeny, with the “Gotta be reality” refrain neatly glancing off the theme.

-

‘Positivity’

Image Credit: Dimitrios Kambouris/WireImage Wonder isn’t just Steveland Morris’ adopted surname, it’s also a theme. Stevie’s sense of agape has always been central to his music, but it is nonetheless rooted in hard political realities that Wonder has long involved himself with as an activist. Hearing him talk about this all explicitly — and, you guessed it, tunefully — in this jaunty number offers its own kind of thrill: Stevie doesn’t often break the fourth wall, and he usually saves his keenly humorous self-awareness for his interviews. (He gets in a playful jab at the press, too, quoting a typical opener: “From your perspective as an African American …”) Speedily speak-singing — it’s not quite rapping — on the verses, Wonder lays out his philosophy: “I’m not saying life sometimes can’t be rough/But you’re never gonna find me saying I’ve had enough.” Is it a little corny? Sure. Is it genuinely uplifting? Goodness, yes.

-

‘Creepin”

Image Credit: Gijsbert Hanekroot/Redferns/Getty Images Motown wanted the new album now. Stevie had recorded 30 songs for Fulfillingness’ First Finale — he’d wanted it to be a double album before cutting it to a single. One night, nearing a deadline, co-producer Robert Margouleff called the assistant engineer, Peter Chaikin, and told him to “set up for mixes.” Then Stevie called: “Set up for tracks.” He then came in and recorded “Creepin’,” from top to bottom, instrument by instrument, vocal by vocal, in a single night, starting with the drums. “If you listen to ‘Creepin’,’ it’s a painting,” Chaikin told OkayPlayer. Wonder’s timekeeping was oddly nuanced — because, the young engineer quickly realized, he was creating openings for the other instruments to fill in: “If he had been a drummer playing with a keyboard player, a bass player, and a guitar player, that performance on drums would have been amazing. But to do it, without anything to play against and to hear it all in his head, it was astounding.”

-

‘Hey Love’

Image Credit: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images Stevie’s Sixties Motown career was full of swerves from the usual run of things — live hits, pseudonymous instrumental albums as Eivets Rednow, protest songs — and this is another example — the rare B side that did better than the A on the R&B chart. The groove is spare, a kind of throwback to the label’s earlier sound (see also Martha and the Vandellas’ “Jimmy Mack” from the same year), and the airy landscape lends the canted piano line and Stevie’s fluttering near-falsetto (and occasionally the actual falsetto) a lingering soulfulness — not to mention a funkiness that led De La Soul to sample it prominently on their second album in 1991.

-

‘Love Light in Flight’

Image Credit: Pete Still/Redferns/Getty Images In the midst of filming The Woman in Red, his third film as director as well as star, Gene Wilder showed a “middle cut” to his friend Dionne Warwick, who asked if she could bring Stevie Wonder back for another screening. When Wonder watched it (with help from a sighted assistant), it kicked off a torrent: “Three days later, he’d written two songs,” Wilder said, “and played them over the phone to me. Then he wrote one more, and I thought that was it. I went to France to relax for a week. Then I got a call at 2 a.m. It was Dionne saying Stevie wanted to write more.” That included this effervescent gem — its steps up the scale as quick and graceful as Fred Astaire, its vocal yearning and direct but never simple-minded, yet another Eighties theme that’s better than the movie it’s in.

-

‘If You Really Love Me’

Image Credit: Tom Copi/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images “Between you and me, I’m really just thinking about saying, ‘Fuck it,’” Stevie Wonder told Rolling Stone’s Sue C. Clark in the fall of 1971, adding, “Unless I feel that something is right, I’m just going to do nothing because I think that doing nothing is better than doing something that is wrong.” He was tired of Motown pulling rank on his musical decisions: “Steve’s new album, Where I’m Coming From, has been finished since the end of May 1970, yet it was just released this summer,” Clark reported. It was evident why: Wonder was increasingly defying the label’s orthodoxies. Even a song like “If You Really Love Me” — on the surface another in the smoothly composed string of future supper-club standards Stevie had begun with “My Cherie Amour” — was a little skewed, as Rolling Stone’s Paul Gambaccini noted that October: “This single is quite different from the Motown mold. Stevie literally stops the song on two occasions to deliver a half-sung, half-recited lyric.”

-

‘Send One Your Love’

Image Credit: Paul Natkin/Getty Images Songs in the Key of Life had been a major consensus event, named top album of the year by both the Grammys and the urban-hipster Village Voice’s critics poll (whose next winner, Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols, received zero Grammy nominations). It would have been a tough follow-up under any circumstance. Wonder’s next album, Stevie Wonder’s Journey Through “The Secret Life of Plants,” took three years to arrive, was also a double LP, and was largely an instrumental soundtrack to a documentary. It did badly with the critics. It didn’t sell. Yet it had one sizable hit. “Send One Your Love” is one of Wonder’s slinkiest ballads, and if its lyrics can seem simple-minded on paper (“With a dozen roses/Make sure that she knows it/With a flower from your heart”), the commitment of his vocal makes it soar. It was Wonder’s second Adult Contemporary Number One (“You Are the Sunshine of My Life” was the first), a radio format that would become increasingly important to him.

-

‘You Met Your Match’

Image Credit: PA Images/Getty Images The credit on the Tamla seven-inch listed Don Hunter as this record’s sole producer. But the Motown logs — as recounted in the liner notes to The Complete Motown Singles Vol. 8: 1968 box set — settle the matter: This is the first recording that Wonder officially (if not, you know, officially) produced. What an entrance: alongside Hunter, with whom Wonder began a songwriting as well as studio partnership, Wonder outfitted “You Met Your Match” with a peerlessly funky track, heavy on bongos, a dual cheaters’ anthem of the type Stevie would make hits with for years to come (see Number 50). Hunter’s advice would later help Stevie find his own management and led to renegotiating his Motown contract as an adult.

-

‘Happy Birthday’

Image Credit: Francois LOCHON/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images When Wonder began to campaign for a holiday dedicated to Martin Luther King Jr., he didn’t just write a check or play a show. He hit the pavement, joining a 1981 march in support of the holiday in D.C., joining 50,000 other supporters even after a series of snowstorms plagued the district. He also wrote a song for the occasion-to-be. “Happy Birthday” was Stevie working completely alone: He played piano, Fender Rhodes, vocoder, drums, bass melodian synthesizer, and Fairlight synthesizer, and the shiny groove became both a sunny hit and effective propaganda for the cause. Shortly after the holiday was made official in early 1984, Wonder played D.C.’s Capital Centre and told the audience, “Congratulations to all of you.… We owe a lot to the fact that we live in a country where the political process of democracy still works.”

-

‘I Just Called to Say I Love You’

Image Credit: Thierry Orban/Sygma/Getty Images Boy, did people hate Stevie’s schmaltziest song when it came out. “Unquestionably one of Wonder’s worst efforts on record,” Variety seethed. “A bland MOR tune with banal lyrics and no beat to speak of.… One can only guess that he had to get it out in a rush and hope that he never waxes anything like this again.” By contrast, a Motown executive predicted that “I Just Called to Say I Love You” — part of the soundtrack to the Gene Wilder comedy The Woman in Red — would become “the biggest single in the history of Stevie Wonder,” and was right: It spent three weeks atop the Hot 100, and topped the charts in 19 countries. No wonder — that tune is durable, the biggest earworm Wonder ever composed, itself some kind of feat. Whether you resist or admire this song, it will taunt you.

-

‘Bird of Beauty’

Image Credit: Gijsbert Hanekroot/Redferns/Getty Images Stevie had a long working friendship with the Brazilian bandleader Sérgio Mendes, who was a direct influence on “You Are the Sunshine of My Life” two years earlier and someone who recorded Stevie’s songs frequently. Better yet, he requested Mendes pen a verse for this song in Portuguese, which Wonder then sang on the album. “I was so charmed by his ‘American’ accent on the Portuguese,” Bonnie Bowden, a singer in Mendes’ band that Sérgio sent to coach Stevie, later said. Robert Margouleff recalled to OkayPlayer about the session: “Malcolm [Cecil] would read the song aligned with the time ahead of Stevie singing it. The song ‘Bird of Beauty’ is when he sung in Portuguese. I remember the night that we did that. It was mind-bending. Stevie was singing almost right on top of hearing the words in Portuguese in his headphones.”

-

‘I Wish’

Image Credit: ABC Photo Archives/Disney General Entertainment Content/Getty Images “We were going to write some really crazy words for the song ‘I Wish,’” Stevie told Musician magazine in 1984. “Something about ‘The Wheel of ’84.’ A lot of cosmic type stuff, spiritual stuff. But I couldn’t do that ’cause the music was too much fun — the words didn’t have the fun of the track. The day I wrote it was a Saturday, the day of a Motown picnic in the summer of ’76. God, I remember that ’cause I was having this really bad toothache. It was ridiculous. I had such a good time at the picnic that I went to Crystal Recording Studio right afterward, and the vibe came right to my mind: running at the picnic, the contests, we all participated. It was a lot of fun, even though I couldn’t eat the hot dogs.… From that came the ‘I Wish’ vibe.” Stevie knew he got it right when he hit upon the refrain: “Couldn’t come up with anything stronger than the chorus, ‘I wish those days (claps) would (claps) come back once more.’ Thank goodness we didn’t change that.”

-

‘Skeletons’

Image Credit: Larry Busacca/Getty Images Stevie was a loud and proud fan of Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, and you can hear their combo of stepping-stone bass line and long-note melody line at work on this none-more-’87 jam, an R&B Number One that summer and his final American Top 40 hit. The bass line has the pointiest shoulders in Wonder’s catalog — a younger listener will be forgiven for thinking of the Seinfeld theme. But that seeming affability hides a ready pair of teeth. “Things are getting real funky/’Round the old corral … It’s the stinkin’ lies you tell,” he seethes, targeting Ronald Reagan as readily as he once had Nixon.

-

‘Shoo-Be-Doo-Be-Doo-Da-Day’

Image Credit: NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images When Wonder, Hank Cosby, and Sylvia Moy began working on this song, Moy said, “We had really more or less run out of titles.” So, Stevie suggested a title of literal nonsense. “It says something and then it doesn’t, and yet it says a lot,” Moy added. The track’s dark, funky feeling came straight from the singer — not just his smoky vocal, but his brand-new clavinet, which would become his musical signature over the next few years.

-

‘For Your Love’

Image Credit: Bertrand Guay/AFP/Getty Images Many of Stevie’s classic ballads up and announced themselves as such immediately. But this one took some time to seep in. The first single from Wonder’s Conversation Peace — his first non-soundtrack album in eight years — was seemingly buried in Nineties CD bloat: track 10 of 13. But a full listen reveals why: that’s where it works best, the yearning opening notes both a rhythmic and melodic half-turn from the finish of its jazzy predecessor, “Sensuous Whisper.” It wasn’t a massive hit, reaching only Number 11 on R&B charts — but the yearning vocal (which earned Wonder a Grammy for male R&B performance) and lush melody have made it a durable favorite: It’s gotten more than 12 million Spotify plays, magnitudes more than the others on the album. Like the rest of Conversation Peace, it was composed while Stevie was in Ghana in the mid-Nineties. This past May, on his 74th birthday, he became a Ghanaian citizen, ready to become active in creating jobs for the nation’s large youth population. “The youngest generation is in Africa,” he told the BBC. “We need to begin to think about how their greatness can shine.”

-

‘All I Do’

Image Credit: Aaron Rapoport/Corbis/Getty Images This song has one of the twistiest back stories of Stevie’s career — and that of Motown Records. Wonder had co-written “All I Do Is Think About You” as a teenager, along with Clarence Paul and Morris Broadnax. It was recorded by Motown artists Brenda Holloway (melancholic) and Tammi Terrell (a pop torch number) in the mid-Sixties, but both versions went unreleased at the time, not surfacing until the 2000s. Wonder then reworked the song, and shortened its title, for 1980’s Hotter Than July. Rather than the billowing vibes-and-strings sizzle of the earlier versions, Stevie arranged the song for a boisterous small combo, led by understated electric piano, playing to a soft disco beat. This modest take became a deserved hit, a decade and a half after it was written.

-

‘My Cherie Amour’

Image Credit: Screen Archives/Getty Images Wonder’s fecundity came early. Take “My Cherie Amour,” which the teenaged genius wrote in an hour at the piano of the Michigan School for the Blind during his senior year there. “‘My Cherie Amour’ was a song I had in the can … for a long time,” Wonder said in 1984. “And I played the song for Hank Cosby, who liked it a lot and came and produced it. Originally it was ‘Oh My Marsha,’ but Sylvia Moy came and changed the words to ‘My Cherie Amour.’ I had a girlfriend named Marsha. Well, we broke up, so it was a good thing they changed it.” This sophisticated ballad, its airy violins underlining its Great American Songbook sturdiness, initially puzzled the Motown brass — ”I don’t even think they knew what to do with me at that point,” Stevie said — and was initially relegated to a B side. Instead, it went Top Five on the Billboard Hot 100 and R&B charts, and became an instant standard.

-

‘I Was Made to Love Her’

Image Credit: Hulton Archive/Getty Images Henry Cosby, one of this song’s co-writers and the record’s producer, called this tune “the beginning of disco,” because the melodic line Stevie had given him was four bars, so he just repeated them through the entire song. But the track hardly felt repetitive — the arrangement blossoms, Stevie’s harp is some of his sharpest, and bassist James Jamerson took liberties, playing the first bar exactly the same every time but almost nothing else. It’s purely exuberant; no wonder the Beach Boys covered it the same year on Wild Honey. And it was the recorded debut of Stevie’s key instrument of the late Sixties: the clavinet.

-

‘I Believe (When I Fall in Love It Will Be Forever)’

Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images The closing theme from a statement of bruised romanticism — here’s a case of a song that works equally well in a film as it does on its home album, and despite their obvious differences, does so for the same basic reason. Closing out Talking Book, “I Believe” has a cosmic rightness — all of the album’s cosmic hope and romantic realism taking flight together. At the end of High Fidelity, those soaring synthesizers signify the inchoate hopes of Rob and Laura, reunited after a rupture. It suits the song to a tee: a horizon glimpsed, a happy ending with an asterisk.

-

‘You Haven’t Done Nothin”

Image Credit: David Redfern/Redferns/Getty Images Fulfillingness’s First Finale, Wonder’s second Grammy winner for Album of the Year, was released in July 1974; a month later came the issue of this single from it — two days, coincidentally, before the resignation of the song’s very subject, Richard Nixon. To be fair, a lot of pop music was taking shots at the beleaguered — and law-breaking — president right about then, from small-timers like the Honeydrippers (“Impeach the President,” one of the most sampled hip-hop breaks) to soul royalty James Brown (“Funky President”). But Stevie’s stomped the hardest — the Moog bass line is utterly implacable, so are the tom-toms, and so is his vocal leer, curling with menace at the end of every line.

-

‘Master Blaster (Jammin’)’

Image Credit: Rick Diamond/Getty Images Wonder had first played with Bob Marley and the Wailers in 1975, at a stadium show in Kingston, Jamaica — a charged performance, with Bunny Wailer and Peter Tosh rejoining Marley onstage for the first time in two years (and the last time, period) — and later performed together onstage in Philadelphia in 1979. But their mooted fall 1980 tour together fell by the wayside when Marley was diagnosed with cancer. Stevie had already given Bob his flowers that summer, by way of this joyous homage to the Wailers’ powerful groove, with its power-of-music ethos echoing Marley’s “Trench Town Rock.”

-

‘Don’t You Worry ‘Bout a Thing’

Image Credit: RB/Redferns/Getty Images Stevie had recorded in excess of 50 songs in different stages of development for Music of My Mind; he would write 30 more for Fulfillingness’ First Finale — and in between came two albums (Talking Book and Innvervisions) he kept adding things to at the last minute. “If I’m not working, I’m writing. Even if I’m working, I’m still writing,” he said in 1971. It’s a testament to a lot of hard work that he made it sound so effortless. In fact, he could write songs about making it all seem effortless, and this is one of the greats in that category. Better yet, he pitches it as if the listener is the one having all the adventure while Stevie sits back and waits patiently for you. Uh-huh. Sure.

-

‘We Can Work It Out’

Image Credit: Fin Costello/Redferns/Getty Images The Beatles figured largely in Stevie’s musical cosmology — they “influenced the whole idea of me playing all the instruments myself,” he told Details in 1995. And, of course, Wonder worked with Paul McCartney — their duet, “Ebony and Ivory,” was a six-week Number One in 1982. The most fruitful of these détentes on record is Stevie’s reconfiguring of the Fabs’ 1966 classic, a single that matched Paul’s indefatigable optimism with John’s exasperated bridge. Stevie takes it over completely with a sharp, clavinet-led groove inspired by Memphis R&B rivals Stax Records, turning the vocal into a call-and-response (“Try to see things my way” — “Hey!”) and upping the urgency by a thousand. Not yet 21 and he was already improving on the Beatles — what couldn’t he do?

-

‘Heaven Is 10 Zillion Light Years Away’

Image Credit: PL Gould/IMAGES/Getty Images In 1973, the week Innervisions was released, Stevie was in the front seat of a car that collided with a truck carrying lumber; a log came loose and crashed through the windshield, hitting Stevie in the forehead and putting him in a four-day coma. (He still has a scar.) Wonder took a few months off and then began writing and recording at a torrential pace. “I’ve come to realize my time on Earth is not yet done and there are things to do,” he told Rolling Stone the following February. “I want to travel. I believe I only have one iota of the knowledge I’d like to have when I leave this life.” The resulting album, Fulfillingness’ First Finale, was his most introspective, and in that mode, it crested with this careful consideration of God’s existence. “A mellow, easy-rolling tune sweetens the zeal of ‘Heaven Is 10 Zillion Light Years Away,’” Ken Emerson wrote in his Rolling Stone review of the album, adding that the song “also conveys the calm confidence of Wonder’s devotion.”

-

‘Do I Do’

Image Credit: BSR Agency/Gentle Look/Getty Images Not only did Wonder pioneer the greatest-hits-package-with-new-bonus-songs concept with 1982’s Original Musiquarium — four LP sides, four new tunes — he ended the whole thing with one of his greatest songs. It was proof of his creativity — only a genius like Wonder would have considered “Do I Do” an outtake. Over 10 minutes long, it’s his most showing-off track ever, from the fusion riff at its center — a tasty cousin to “Contusion” — to its pseudo-James Brown section leading into Stevie’s halfhearted (and funny) attempt to rap, a style that made Wonder a rarity among his Sixties-bred peers for championing. (He even demonstrated sampling on MTV in 1986.) “Do I Do” is a showstopper, with Wonder and bassist Nathan Watts playing all the way to the last note — a tongue-in-cheek finish for both song and collection.

-

‘Isn’t She Lovely?’

Image Credit: Allan Tannenbaum/Getty Images Stevie refused to cut this song’s six-and-a-half-minute running time for a seven-inch single, in America anyway. Overseas, “Isn’t She Lovely,” a paean to the birth of his daughter, Aisha Morris, was yet another hit from Songs in the Key of Life — and in America, plenty of radio stations played the record anyway. The bright melody brings forth one of Wonder’s most passionate performances — he’s the proudest papa around, and everyone is getting a cigar. And Wonder’s harmonica playing — an entire verse long, placed between the actual first and second verses, and then throughout the long coda — is as piercing and personal as he ever sounded. Bob Dylan said it best: “He played the harmonica incredible, I mean truly incredible.”

-

‘For Once in My Life’

Image Credit: GAB Archive/Redferns/Getty Images Maybe the most surprising thing about this song is that it wasn’t written by Stevie Wonder — the lyric seems tailor made for him, particularly given he’d already hit with the thematically similar and self-co-written “I Was Made to Love Her.” Not only that, Wonder hadn’t even recorded it first — there were more than half a dozen versions, demo’d and released and sitting on shelves, before he got his hands on it. He didn’t want to at first — Wonder was interested in his own songs first, and had begun to pick his covers carefully. But once convinced, he tore into it, giving a commanding performance, not least what may be his finest ever harmonica solo.

-

‘Do Yourself a Favor’

Image Credit: Chris Walter/WireImage In his Red Bull Music Academy lecture, George Clinton described the rock scene of late-Sixties/early-Seventies Detroit thusly: “Ted Nugent and Amboy Dukes, Iggy Pop [and] the Stooges, MC5, John Sinclair, Parliament-Funkadelic. And weird as it sounds, Stevie Wonder, because he was just getting started.” You can hear that all over this blasting funk-rock masterpiece — a track that can hang with anything on Maggot Brain or Fun House. Stevie hasn’t yet begun to work with Robert Margouleff and Malcolm Cecil, but it’s clear why he wanted to — the screaming clavinet and growling bass are gunning for new textures that synthesizers would increasingly offer. You can also hear the despairing lyrical style of the early Funkadelic albums: “Dig a grave and step right in.” Stevie does give it a lift with the chorus, which is nevertheless as dystopian as he ever got: “Educate your mind/Get yourself together/Hey, there ain’t much time.”

-

‘Boogie on Reggae Woman’

Image Credit: Gijsbert Hanekroot/Redferns/Getty Images Stevie once described the pleasures of playing harmonica to a Rolling Stone reporter: “It’s really like a small sax,” he said in 1971. “There’s so much you can do with it. I try to play it with a sax, or a certain feeling. It’s another color of music. You can express the way you feel. You can get a vocal quality.” You get one of his honey-toned solos on this undulant, unrelenting funk bomb — it’s a sly, direct come-on, just like the rest of the tune, one of Wonder’s plain sexiest. (And just to be clear, it’s not reggae.) “Boogie on Reggae Woman” is one of the ultimate examples of how differently and equally expressive Wonder is on all instruments; each overdub comes with its own set of idiosyncrasies, none of it could be anybody else, and the sum total is nigh irresistible.

-

‘Fingertips, Part 2’

Image Credit: Daily Mirror/Mirrorpix/Getty Images “I never did realize it would take me so long to lose that ‘Little’ Stevie Wonder tag,” Wonder said in 1972. “There are times when I wish I’d only just started right this minute. It’s amazing how many people still think of me as this sweet young kid.” But that sweet young kid was like nobody before him. He was only 12 when “Fingertips Part 2” topped the Hot 100, for starters. It was basically an improvisation, recorded live, not even really a song — all key Motown no-no’s (though live recordings were hot, thanks to James Brown’s bestselling Live at the Apollo). And yet, this record incinerated — the band is locked in, and Stevie on harmonica is leading it without a hitch. When he plays a snatch of “Mary Had a Little Lamb” near the end, it’s funny because he’s a kid and funny because he’s knowingly playing off the fact that he’s a kid. He would continue doing so years later with this song, long after everyone stopped calling him “Little,” using a vocal synthesizer in concert during the mid-Eighties to change his voice back to its preadolescent tone.

-

‘Sir Duke’

Image Credit: Richard E. Aaron/Redferns/Getty Images “Sir Duke” was written shortly after the 1974 death of Duke Ellington and taught to Stevie’s band Wonderlove in “about 45 minutes,” drummer Raymond Pounds told OkayPlayer. By the time it appeared on Songs in the Key of Life, it stepped into an era of winking, dance-ready retro — Dr. Buzzard’s Original Savannah Band, Donna Summer’s “I Remember Yesterday,” full of razzmatazz-y horns over disco beats. Wonderlove guitarist Michael Sembello recalled falling asleep during the session but was still psyched by the music: “I would wake up every few minutes and ask, ‘Is it time yet?’ They would tell me no. Two days went by, and it was like 6:00 a.m. and Steve said, ‘It’s time!’ … The reason I was able to do it was due in part to everyone being so energized and fueled to do the music.… To see the excitement from Stevie Wonder, you can’t help but become energized. When you were in the same room with him, your IQ went up by 50 points.”

-

‘You Are the Sunshine of My Life’

Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images One of the most beguiling records ever made, “You Are the Sunshine of My Life” threaded an improbable needle: a bossa-nova-inflected supper-club standard — with instant covers by Frank Sinatra and Perry Como to prove it — filtered through the big-tent exuberance of post-Woodstock rock and soul. It features some of Stevie’s loosest and most exuberant drumming, and Sly and the Family Stone’s multi-vocal roundelay is echoed at the top, with the opening lines given to backup singers Jim Gilstrap and Lani Groves. But when Stevie comes in, he delivers what may be, line for line, his greatest vocal performance — every line perfectly measured, every nuance landing with ease and force. It offered something old and something new, the perfect thematic statement for his breakthrough album Talking Book — but even better is the single mix, which adds horns and appears on later compilations like Original Musiquarium.

-

‘As’

Image Credit: Richard E. Aaron/Redferns/Getty Images Gospel has always figured heavily into Wonder’s music, from early singles like “Work Out Stevie, Work Out” (1963) to “Signed, Sealed, Delivered (I’m Yours)” to “Heaven Is 10 Zillion Light Years Away” — but the musical framework has seldom been so unadorned in his catalog as on “As,” the glorious centerpiece of Songs in the Key of Life’s fourth LP side. The wait for that album got so feverish that Motown began selling T-shirts saying “We’re Almost Finished.” (Stevie wore one.) With one of Wonder’s most diaphanous melodies, some of his fiercest drumming, and an appearance of his gravel-heavy, angry-preacher voice, it may be his most heartrending recording. He also got some help from another keyboard player: “I remember calling back to my friends in Detroit, telling them I just finished playing with Herbie Hancock,” bassist Nathan Watts said.

-

‘Living for the City’

Image Credit: Echoes/Redferns/Getty Images Lenny Kaye’s Rolling Stone review of Innervisions commended Wonder’s lyrical range: “His concern with the real world is all-encompassing, a fact which his blindness has apparently complemented rather than denied.” This is the prime example, on the album and in the Wonder catalog. Years before hip-hop sampled it for countless skits, long before Spike Lee utilized it wholesale for the searing crack-house sequence of Jungle Fever, Wonder put the most resonant bit of audio drama on a pop hit — ever. Granted, you didn’t hear the mid-song playlet on the radio in the Seventies; the single edit excised it. But the album version threw the gauntlet for Wonder’s new audaciousness, with a full-blown scenario — the young man he’s singing about arrives in the city, gets set up, is sent away for a decade, and returns to the city, destitute and homeless. It’s devastating work, helped by various associates. The judge was Wonder’s lawyer Johannon Vigoda, while the prison guard who utters the hip-hop staple — “Get in that cell, n***er” — was voiced by “a janitor at the studio,” Wonder recalled. “A white janitor [laughs]. It was right down his alley.” Motown advertised Innervisions with the tagline “Listen and see” — this is why.

-

‘Uptight (Everything’s Alright)’

Image Credit: © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Getty Images Wonder nearly lost his contract in 1965. His voice was changing; he wasn’t having hits. At Motown, the latter was a no-no, and the former didn’t help. Then staff writer Sylvia Moy lobbied to work with him, bringing in Hank Cosby and asking after Stevie’s own songs. “He would come up with pieces of tunes from the keyboard,” Moy said. “He played through everything, and I didn’t like anything.” Stevie had one more idea, which went: “Baby, everything is all right, uptight.” Riding a powerful rhythm track that echoed the Rolling Stones’ “Satisfaction,” his youthful high end distilled into a hard brass tenor, the first reinvention of Stevie Wonder was complete — and a hit, Number One on the Billboard R&B chart and Number Three on the Hot 100.

-

‘Higher Ground’

Image Credit: David Redfern/Redferns/Getty Images “With Innervisions, I was going through a lot of changes,” Stevie told RS in 1974. “Although I didn’t know we were going to have an accident, I knew I was undergoing changes. ‘Higher Ground’ is the only time I’ve ever done a whole track in one [sic] hour, and the words just came out. That’s the only time, and that’s very heavy.” This story has had variations over the years — more recent accounts cite the studio time as three hours, which seems more likely. But even that is an incredible burst of studio activity for a recording as letter-perfect as this one. “Higher Ground” has a visionary force that’s both immediate and otherworldly. It’s urgent — a song about reincarnation that takes the topic seriously — but also makes it seem like the best idea anyone’s ever had, like striving to be your best self as many times as it takes to reach satori is more fun than anything. When the Red Hot Chili Peppers wanted to ramp up their game, this is the song they covered. When Stevie appeared this August at the Democratic National Convention, this is the song he played.

-

‘Signed, Sealed, Delivered (I’m Yours)’

Image Credit: Trevor Dallen/Fairfax Media/Getty Images He was ready. It was a new decade, he’d been itching to make his own records his own way from his mid-teens, and in the summer of 1970, the Spinners’ “It’s a Shame,” which Stevie had co-written and, finally, produced alone, had reached the R&B Top Five. The story of Wonder’s autonomously creative Seventies usually begins with his pair of 1972 masterworks, and there’s no question that Music of My Mind and Talking Book marked a startling transition. But before Stevie got to leave the Motown formula behind, he had to master it, and after this scorching record, nobody could question that he had. Every note of “Signed, Sealed, Delivered (I’m Yours)” soars with confidence. Nobody could have been totally surprised by what followed.

-

‘Superstition’

Image Credit: Soul Train/Getty Images There is no greater or more complete self-reinvention in modern pop than the metamorphosis of Little Stevie Wonder, Motown hitmaking cog, to Stevie Wonder, fully adult self-defining genius, and there is no more definitive marker of that shift than this record. Originally meant as a demo for Jeff Beck, Wonder threw it together quickly, but it was soon apparent that he was going to have to keep it for himself — the track was just too good. It got even better when Stevie sang the sharpest-edged lyric of his career: “When you believe in things that you don’t understand, then you suffer/Superstition ain’t the way.” There was no looking back — Wonder had turned the corner for good. “I hate labels where they say, ‘This is Stevie Wonder, and for the rest of his life, he will sing ‘Fingertips,’” he fumed in 1973. After “Superstition,” nobody said anything like it again.