When Led Zeppelin broke up in 1980, Robert Plant was left to answer a complicated question: What do you do when you have already reached the top?

He’d been struggling to balance his personal and professional priorities even before the band’s sudden dissolution. Plant’s five-year-old son Karac died in 1977 of a stomach virus while Led Zeppelin was out on tour, sending Plant into something of an existential crisis.

“I just thought: ‘What’s it all worth? What’s that all about? Would it have been any different if I was there, if I’d been around?'” he mused in 2020. “So I was thinking about the merit of my life at that time, and whether or not I needed to put a lot more into the reality of the people that I loved and cared for – my daughter and my family generally.”

Just three years later, John Bonham was dead too, effectively cementing the band’s end. Following that, Plant seriously pondered whether his musical career was over for good.

After all, he’d already toured the world and achieved all the global success he could have desired. What else could there be? “Obviously I was sitting on my arse after we’d lost John,” Plant said in his first post-Led Zeppelin interview. “I was thinking: ‘What happens next?’ I had no idea at all.”

Plant decided that quitting wasn’t an option, but embarking on a solo career could be. “I sat in a room with Atlantic Records and [former Led Zeppelin manager] Peter Grant, talking about the solo thing,” he remembered in 2020. “I said: ‘Look, there’s no other way to do this, really. I’ve got to keep going because I’m 32 years old and I haven’t actually felt anything else other than this juggernaut success thing. I need to find out what the other side of it is like.'”

One of the first steps was finding new people to connect with in the studio. Enter Phil Collins, who was personally familiar with launching a solo career and separating oneself from a band of intense fame. He approached Plant bluntly: “Phil was such a huge fan of John [Bonham] that he sent me a message: ‘I’d really like to help you, because this must be one of the toughest things you’ve ever had to do, musically.'”

The recording process, as Plant recalled it, was fast and furious. Collins was not afraid to speak his mind, which turned out to be just what Plant needed in the studio. “We were cutting backing tracks non-stop,” Plant said. “And if he didn’t like something, he’d stop halfway through, stand up and tell people why it wasn’t quite right. I loved that because I was still tiptoeing around, not knowing how to deal with other musicians.”

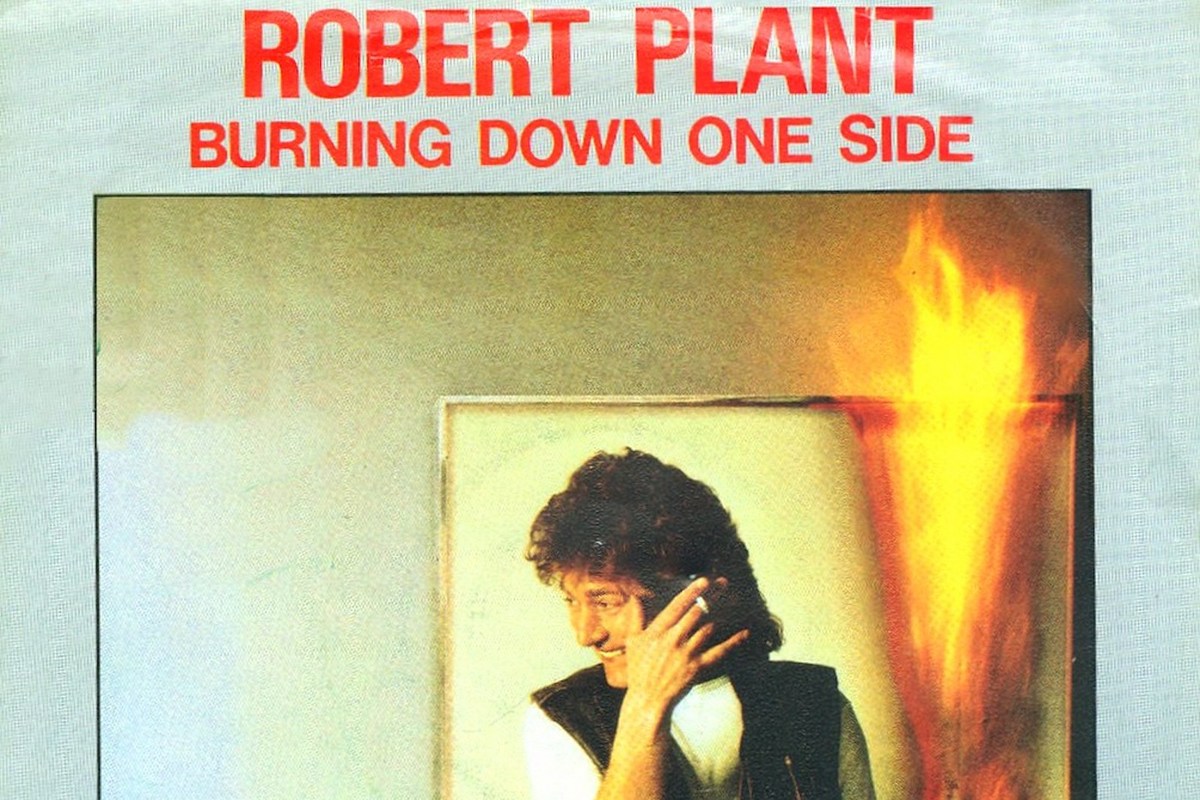

Perhaps the best evidence of Plant’s newfound collaborative spirit is “Burning Down One Side,” the song that became the lead-off track on 1982’s Pictures at Eleven. Plant shared writing credits with guitarist Robbie Blunt and keyboardist/synth player Jezz Woodroffe. Collins played drums, as he did for most of the album’s tracks, and Paul Martinez played bass.

Watch Robert Plant’s ‘Burning Down One Side’ Video

“I knew Robbie Blunt really well, from being around [North Worcestershire],” Plant said. “He’s a very lyrical guitarist, a beautiful player.” Blunt would go on to play on two more Plant solo albums, 1983’s The Principle of Moments and 1985’s Shaken ‘n’ Stirred.

Through the ’80s, Plant would frequently be asked if working with another guitarist was challenging, after partnering with Jimmy Page for a decade. “Jimmy needs a community workshop, and he needs to put his trust and his faith and his vulnerability into someone,” Plant later told Rolling Stone. “We shared something, and that’s fine. It’s just that the way that we do things now is different.”

Plant relished working with new people and shedding at least a little bit of his past. “It’s great fun at the moment, very enjoyable,” he said at the time. “I’m learning new things every day, I’m meeting all kinds of new people in the business – and surprising them all, because they all thought I was some kind of demon.”

One thing Plant would never be able to shed was his distinct singing voice. “Burning Down One Side,” with its repeated refrain (“Ooh I need your love, yes I need your love“) and imagery of a runaway woman “playin’ hooky” with Plant’s heart, wouldn’t have sounded out of place on a Led Zeppelin album. He said this was inevitable: “There are similarities, of course,” Plant acknowledged, “but that’s got to be due to the fact that I’m singing and writing, and this is how I’ve sung and written since the beginning of time.”

It was also 1982, however, and synthesizers were playing a more dominant role in popular music. Combined with new writing partners, “Burning Down One Side” occasionally sounded unlike anything Plant had participated in previously. “As you can imagine, I took a million pains to try and create my own individual sound,” Plant emphasized. “I was just trying to pull away as much as I could … but then again you can only pull away so far. I wanted to leave Zeppelin the way it was and … just pull those reins a little to the right.”

Woodroffe recognized the risk Plant was taking. There were bound to be Led Zeppelin fans who weren’t keen on Plant’s new direction. “What we did was so totally different, yet it was the same voice and it was the same Robert on stage,” Woodroffe told Electronics and Music Maker magazine in 1986. “He was very brave to do that, but on the other hand, if he hadn’t done that, he wouldn’t have done anything.”

“Burning Down One Side” quickly the most popular number from Pictures at Eleven, reaching No. 3 on Billboard‘s “Top Tracks” chart before its stand-alone release in September 1982. The single only reached No. 64 on the Hot 100, and No. 73 on the U.K. singles chart – but Plant was mostly unfazed by this. He’d braced for the worst but had discovered some success.

“I was expecting to get a hammering from everybody,” he said at the time. “I don’t really know why, because I’m proud of what I’ve done.”

The Best Song From Every Led Zeppelin Album

Choosing the best song isn’t easy, since many of their LPs come together as a piece – and they include so many classic tracks.

See Robert Plant Among Rock’s Most Expensive Out-of-Print LPs